Although it only saw combat action in the closing weeks of the First World War, the Model 1918 Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) proved to be the best automatic rifle developed and fielded during the war. Manufactured from 1918 to early 1919 by Colt, Winchester and Marlin-Rockwell, the number of BARs in the U.S. military’s inventory was deemed sufficient to meet the foreseeable demand for automatic rifles in the post-World War I era.

In the 1920s and early ’30s, BARs saw use by U.S. military personnel for a variety of tasks, from guarding the U.S. mail from a rash of armed robberies to protecting American interests in Central America and the Caribbean (the so-called “Banana Wars”)—as well as uprisings in China. The firepower of the BAR and its potent .30 Springfield (.30-’06 Sprg.) cartridge cemented its reputation as the best automatic rifle of the time.

Unfortunately, these attributes of the BAR also attracted the attention of some of the most notorious criminals of the early 1930s, most notably the infamous Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow. Their gang had as many as four military Model 1918 BARs stolen from National Guard armories and used them with deadly effectiveness on a number of occasions. Barrow modified one of the BARs by shortening the barrel and stock.

A typical police officer was generally armed with a revolver and perhaps a 12-ga. shotgun. If a rifle was available, it was normally a lever-action rifle chambered for a relatively low-power civilian cartridge. A few law-enforcement agencies acquired Thompson submachine guns, which had gained much notoriety due to their use by other famous outlaws of the day. However, none of these guns could reliably penetrate heavy steel automobile bodies or even the body armor worn by some of these desperados. Thus, the BAR would “out-gun” anything fielded by most police departments.

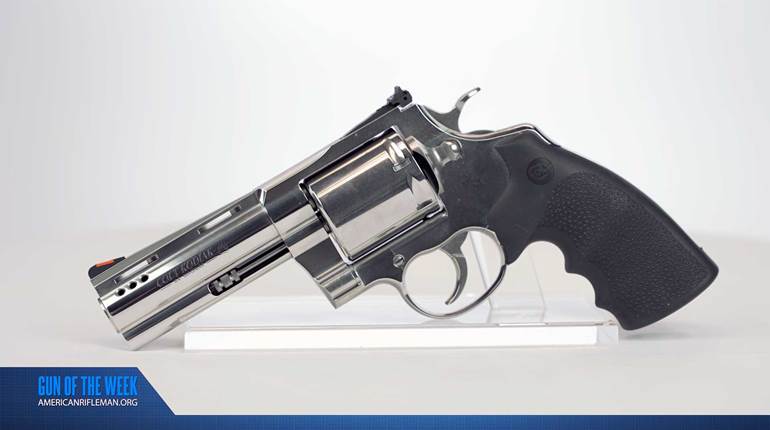

These events resulted in Colt developing an automatic rifle in 1931 specially designed for law-enforcement use. The new arm was designated by Colt as the “R80 Monitor.” The gun had the same basic mechanism as the original Model 1918 BAR, as well as a few features from the “Model 1919” commercial automatic rifle that Colt had previously marketed primarily for export. Later variants of the Model 1919 included the “Model 1925” and the “R75.” An excellent summation of the Monitor was relayed by author James Ballou in his authoritative book on the BAR, Rock In A Hard Place:

“The Monitor, being a direct descendant of the renowned Model 1918 Browning Machine Rifle, retained all the salient features of its parent. Yet the Monitor was notably different in several respects, exhibiting a personality all its own. The receiver was fitted with the pistol grip and ejection port cover as found on the later commercial Machine Rifles (the Model 1919 and the R75 variant), but the Monitor weighed only 16 lbs. 3 ounces compared to the 20.25 lbs. of the R75. This was mainly due to its light, plain, non-quick-detachable 18" barrel, which was 6" shorter than the barrel of the standard military BAR …

“Fire control with such a light gun was enhanced by a distinctive 4"-long bulbous Cutts Compensator which was threaded to the muzzle of the Monitor barrel. Produced by the Lyman Gun Sight Company, this Cutts Compensator resembled earlier versions designed originally for military trials in the late 1920s. The Monitor version had 12 radial slots cut into each side of its upper quadrants, leaving a longitudinal strengthening web on the top center line. This device effectively reduced muzzle climb during full automatic fire by nearly forty percent, and actual recoil more than thirty percent.

“The presence of the compensator made the Monitor amazingly controllable during automatic fire, given the light weight of the gun. Even a small person with little automatic weapon experience could shoot the Monitor accurately and effectively. When set for full automatic, the Monitor’s rate of fire was a nominal 500 rounds per minute, meaning a 20-round magazine would be expended in 2 1/2 seconds. Colt’s also claimed that, with the weapon set for semi-automatic, a trained gunner could deliver 60 aimed shots per minute.

“Firing a 150-grain .30 caliber bullet from the 18" Monitor barrel produced a muzzle velocity of 2,600 feet per second, and a muzzle energy of 2,300 foot pounds. At short police ranges the bullet would penetrate fifty 7/8" pine boards, or a 3/8" thick steel plate. This meant that heavy wooden or metal covered doors, brick or frame dwelling walls and even the heavily armored sedans favored by gangsters, could all be easily penetrated.”

Colt marketed the Monitor exclusively to law-enforcement agencies with no advertisements placed in commercial newspapers or magazines. Regardless of its impressive performance, there was little demand for the Monitor, as most police departments simply did not have the resources to purchase the guns due to the prevailing financial difficulties of the Great Depression. The Monitor sold for $300 in 1931, which, adjusted for inflation, is more than $5,500 today. The first two Monitors were sold to the Charleston State Prison in Boston on March 25, 1931, but subsequent sales were little more than a trickle until the most famous law-enforcement agency in the country began to pay attention to the Monitor.

Enter The FBI

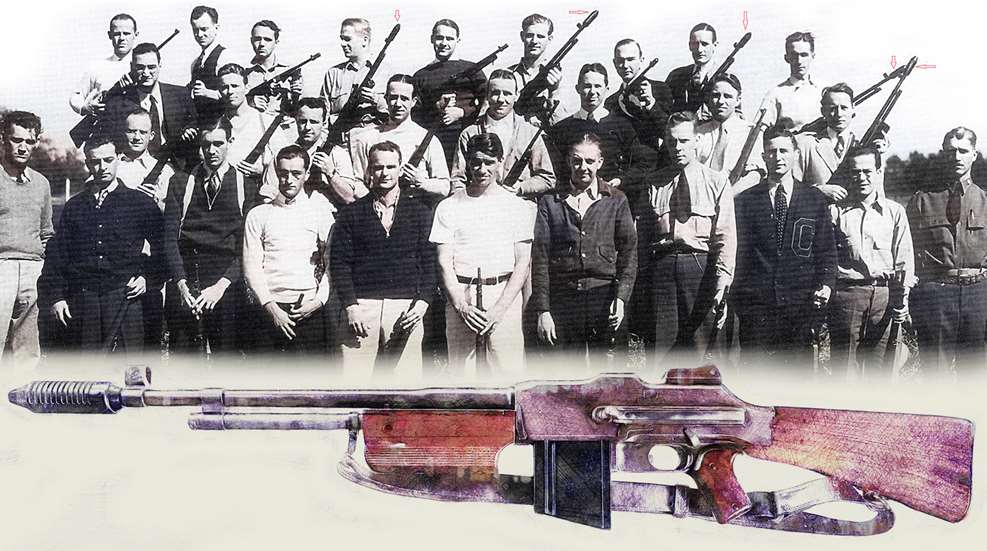

There was one law-enforcement agency that had the budget to purchase new arms, and in 1933, the Federal Bureau of Investigation bought some 90 Monitors. By this time, the “mechanized bandit” phenomenon had reached a peak in the national media. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover wanted to convey to the public—and doubtless the legislators who controlled the federal purse strings—that the Bureau was doing its part to handle the current situation. Hoover commissioned several newsreel-type films showing FBI agents firing Monitors at automobiles on the target range. The Monitors displayed impressive firepower, and the cars were thoroughly riddled with armor-piercing .30-’06 bullets. The obvious inference was that the Monitor-armed FBI agents were more than a match for Bonnie and Clyde and the other BAR-wielding criminals. The Monitor was designated by the FBI as its first official “Fighting Rifle.”

The FBI planned to distribute some Monitors to a number of field offices across the country and retain the rest at the FBI Academy in Quantico, Va., for training purposes. A June 7, 1934, “Division of Investigation” memo revealed that 66 Monitors were slated to be sent to 24 field offices ranging from Los Angeles to New York City. However, as of the date of the memo, only a total of 11 had actually been delivered to five field offices (Cincinnati, Dallas, Detroit, El Paso and Kansas City). Details pertaining to the subsequent distribution of the remaining group of FBI Monitors are not known.

Despite the FBI’s acceptance of the Monitor, subsequent sales were very limited, and Colt only manufactured some 125 Monitors by the time production ceased in 1940. In addition to the 90 Monitors purchased by the FBI and the two sold to the Charleston Prison, the remaining 30-plus guns were sold to police departments, other prisons, banks and security companies.

It is reported that a Monitor was given to retired Texas Ranger legend Frank Hamer by the Colt company. Hamer lent his Monitor to Dallas County Deputy Sheriff Ted Hinton, who was part of his posse, and it was used during the deadly ambush of Bonnie and Clyde in May 1934. Hamer’s Monitor, Serial No. C-103168, is now in the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum in Waco, Texas.

Due to the limited number made and its sales being restricted to law-enforcement-related agencies, the story of the Monitors is not widely known today. Genuine extant examples are exceedingly rare, and very few are in private hands. The Monitor is a little-known, but very interesting, variant of one of the most famous U.S. military arms of the 20th century and John Browning’s masterpiece: the BAR.