By the summer of 1943, the fortunes of war had turned harshly against Italy, Hitler’s Axis partner in Europe. Allied forces had landed on Sicily on July 10, and by August 17, the island was under Allied control. With the stage set for an Allied invasion of the Italian mainland, Mussolini’s grip on the Italian military began to slip, and the Grand Council of Fascism moved to restore the nation’s political power to King Victor Emmanuel III. In late July, Mussolini was arrested and relieved of his duties as Prime Minister. Il Duce was initially imprisoned on the island of Ponza. Italy’s new leaders spent most of August confirming the Italian general staff’s chain of command, as well as opening negotiations with Allied leaders to create an armistice.

Even though they tried to conceal their overtures, the Italian movement towards a peace plan with Allies did not go unnoticed by the Germans—particularly when Mussolini was deposed. Hitler ordered several divisions to move to the south of the Alps, ostensibly to defend against the expected Allied invasion of southern Italy, but also to take control of as much Italian territory as possible. Even as new Prime Minister Marshal Pietro Badoglio proclaimed that Italy would continue fighting the Allies alongside Germany, he also dissolved the Italian Fascist Party.

The original Axis partners in happier times. Mussolini was, at best, a junior partner. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration photograph.

The original Axis partners in happier times. Mussolini was, at best, a junior partner. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration photograph.

On September 3, King Emmanuel and Marshal Badoglio agreed to an armistice with the Allies, and signed the “Armistice of Cassibile,” which was made public five days later. The Italians had pressed for the Allies to make assurances that they would “protect” Italy from the expected German attacks following the announcement. There was no practical way for this to be granted, and as the Italians initially balked, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower implied that a 500-bomber raid on Rome would happen soon if the armistice was not signed promptly—it was and without any amendments.

Italian Anarchy And The Search For Mussolini

When the Italian armistice was announced on Sept. 8, 1943, the nation quickly fell into anarchy, as the military was without orders, and government officials were without centralized direction while wielding dubious authority. One of the foremost Allied demands in the armistice was that Mussolini be turned over as a war criminal. The Italians made preparations to do this, taking care to conceal Il Duce’s location from the Germans—first on the island of Ponza (in the Pontine Islands), then La Maddalena (in Sardinia), and finally on a mountaintop in Abruzzo within the Campo Imperatore, also called the Gran Sasso.

DFS 230 glider, introduced in 1939 and served throughout the war. The later C-1 models had a braking parachute, as well as reverse-firing braking rockets in the nose (the glider could land within 60 feet of its target). Up to nine troops could be carried. An MG15 (7.92 mm) was carried and available for use while landing. Image courtesy of author’s collection.

DFS 230 glider, introduced in 1939 and served throughout the war. The later C-1 models had a braking parachute, as well as reverse-firing braking rockets in the nose (the glider could land within 60 feet of its target). Up to nine troops could be carried. An MG15 (7.92 mm) was carried and available for use while landing. Image courtesy of author’s collection.

In the meantime, the Germans did not wait for the Italian government to sort itself out. Hitler considered the Italian armistice nothing less than a complete betrayal. Consequently, on Sept. 8, 1943, a total of 40 German divisions under the command of Field Marshal Albert Kesselring moved to disarm the entire Italian army in “Operation Asche.” In a fast-moving offensive, German units stationed in Italy, the Balkans and southern France disarmed more than one million Italian troops by September 19. Despite the confusion and lack of leadership, many Italian units resisted, and more than 20,000 Italian troops were killed before the Germans gained control of Italy, Yugoslavia, Greece, Albania and Crete. Sadly, many of the captured Italian troops were not granted prisoner of war status, but rather were classified as “Italian Military Internees” and were sent to Germany to work as forced laborers. As many as 50,000 died in Germany before the war ended.

The Allies invaded the Italian mainland on Sept. 3, 1943 as the British came ashore at Calabria, and then on September 9, the Americans landed at Salerno. Most Italian units offered token resistance before they surrendered. When the German “Operation Asche” disarmed Italian troops on September 19, Italy had become a German-occupied nation throughout the mainland, while they were simultaneously invaded by the Allies in the south. Throughout this tumultuous time, the Germans were diligently looking for Mussolini. Although Hitler assigned this task to several groups within the Reich military and intelligence service, the Fuhrer put his trust in one of his top agents: SS Lt. Col. Otto Skorzeny. Early in 1943, Skorzeny had been chosen to lead commando teams under the direction of the SS Foreign Intelligence Service—men trained in sabotage and espionage. Skorzeny’s first mission (“Operation Francois”) was to coordinate the payment and training of dissident Iranian tribesmen to attack Allied supplies to the Soviet Union that traveled through Iran. Although Operation Francois was not successful, Skorzeny’s personal stock was quickly on the rise.

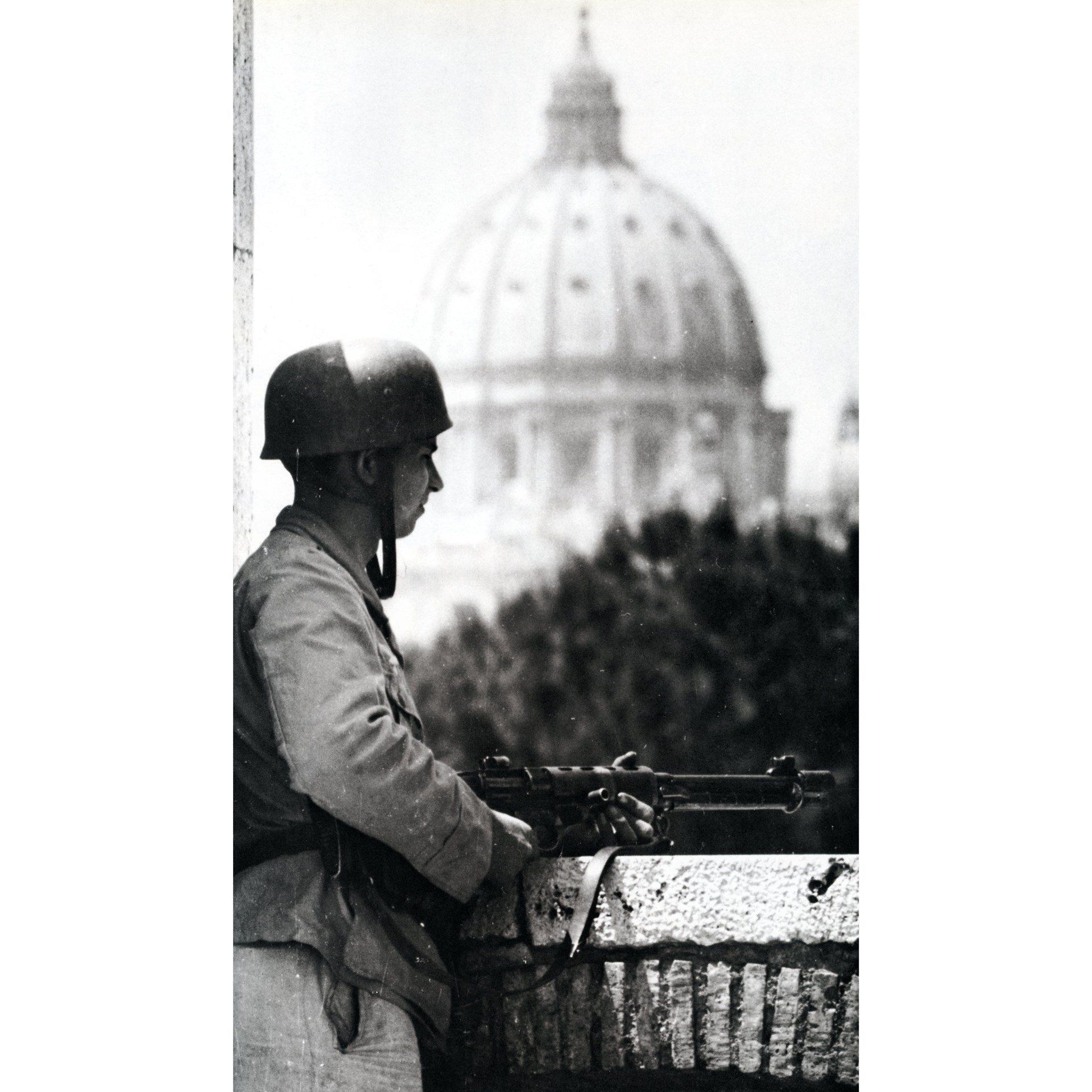

The FG42 in Rome in the autumn of 1943. Image courtesy of author’s collection.

The FG42 in Rome in the autumn of 1943. Image courtesy of author’s collection.

On Sept. 7, 1943, German intelligence intercepted an Italian radio transmission indicating that Mussolini was being held in the mountains near Abruzzi. A postwar US intelligence report translated some of Otto Skorzeny’s notes on the search for Il Duce:

“Rumors that were picked up, bold scouting patrols, and the close cooperation with the German and Italian intelligence officers existing there, brought to light the track of the Duce, which was lost again and again as the days passed. The nervous guards unexpectedly transferred their prisoner fourteen times.

In this reconnaissance activity, an Italian-speaking German officer particularly distinguished himself. Disguised, drinking with Italian sailors, he found about 24 hours before the surrender of Italy the place where the Duce was staying—a villa on a little island. On the day of the betrayal, when the task of being informed about the place of the Duce’s captivity turned into the political requirement of snatching him away from the traitors, Skorzeny went in a high-speed boat to the island to secure his liberation. He found an empty nest. At dawn, the Duce had been flown off by hydroplane to a new hiding place.

The search began again. This time faint traces point to a mountain hotel in the Gran Sasso. Again, patrols went out, using people who knew nothing of their real task. They came back with the report that the lower station of the mountain railway that led to the presumed hiding place of the Duce, had been barred and was guarded by a large detachment of Carabinieri.

Thereupon Skorzeny, at a very great height, flew over the terrain in a recon plane that Gen. Student had placed at his disposal. Skorzeny credited the cooperation of the general as being of decisive importance in this work.”

These Gran Sasso raiders carry plenty of ammunition for their MG42. Image courtesy of author’s collection.

These Gran Sasso raiders carry plenty of ammunition for their MG42. Image courtesy of author’s collection.

German intelligence pinpointed Mussolini’s location as the Hotel Campo Imperatore, set high on a plateau more than 2,000 meters above sea level in the Gran Sasso mountains. The hotel that had been constructed to celebrate Mussolini’s rise to power was now his prison.

In the days leading up to the raid, Skorzeny received little good news about the chance of its success. Skorzeny noted that a ground assault up the steep slope would be hopeless, and that “there remained only two alternatives—parachute landings or gliders.” The Luftwaffe considered a paratroop drop to be too risky and that the men would descend too fast and be scattered all over the mountainside. Likewise, a glider landing was considered exceptionally dangerous as there was not enough clear space to land near the hotel, and the mountain air was too thin for effective glider operations. Skorzeny chose the slight lesser of two dangers—a glider assault. Despite the slim odds of success and the significant possibility of high losses, Skorzeny would find no shortage of volunteers for the mission. He would later say: “It was impossible to give preference to volunteers because everybody applied.”

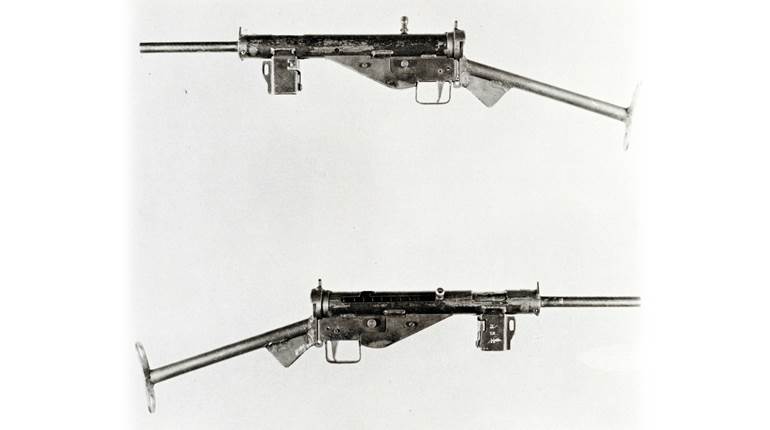

The DFS 230 glider: The wheels seen in this image would normally be dropped once the glider was airborne, with combat landings made on the skid. Exit from the slim aircraft was through the knock-out side panels and from the cockpit. Image courtesy of author’s collection.

The DFS 230 glider: The wheels seen in this image would normally be dropped once the glider was airborne, with combat landings made on the skid. Exit from the slim aircraft was through the knock-out side panels and from the cockpit. Image courtesy of author’s collection.

Operation Oak

On the morning of Sept. 12, 1943, the plan was in place and the troops ready to go. Skorzeny and sixteen hand-picked SS men rode in two gliders while the German paratroopers flew in eight more. Luftwaffe Oberleutnant Georg Freiherr von Berlepsche was in command of the airborne assault, riding in the first glider. Luftwaffe Maj. Harald-Otto Mors was in overall command of the German paratroops during the raid, and Mors led the ground force that secured the cable-car station at the base of the Gran Sasso.

The DFS 230 assault gliders were brought in from Southern France. The DFS 230 offered an excellent glide ratio of 8:1, allowing it to be released at a greater distance to help mask the sound of the towing aircraft. Each DFS could carry nine fully equipped troops (plus the pilot) and was equipped with a parachute brake as well as nose-mounted braking rockets. Even so, this landing would be particularly challenging.

The DFS 230 was an assault glider and the Fallschirmjager were ready to fight the moment the aircraft came to a stop. In this training photo, an MG 34 (7.92 mm) gunner leads paratroops armed with MP40 SMGs and P08 pistols (9 mm) into battle. Image courtesy of author’s collection.

The DFS 230 was an assault glider and the Fallschirmjager were ready to fight the moment the aircraft came to a stop. In this training photo, an MG 34 (7.92 mm) gunner leads paratroops armed with MP40 SMGs and P08 pistols (9 mm) into battle. Image courtesy of author’s collection.

Despite his aerial reconnaissance of the hotel, Skorzeny had not identified a field of large, jagged boulders scattered among the gliders’ landing zone. Although some of the gliders were damaged by the rocks, only glider No. 8 was wrecked, with all men aboard suffering injuries. Skorzeny’s two gliders ended up landing first, coming to rest less than 20 yards from the hotel.

The suddenness of the attack stunned the nearly 200 Italian Carabinieri guards. Skorzeny had brought along Italian Gen. Fernando Soleti, a fascist and pro-German, to order the guards not to shoot. As the guards hesitated, Skorzeny and his men rushed past them—Skorzeny knocked out the hotel radio operator and smashed his equipment. With Mussolini in German hands, Skorzeny angled to intimidate the superior guard force to surrender. He summoned the commander, a colonel, and presented an ultimatum: “I ask for your immediate surrender, Mussolini is already in our hands, and we hold the building. If you want to avert senseless bloodshed, you have 60 seconds to decide!” A few anxious moments passed, but there were no shots fired. The Italian colonel approached Skorzeny and gave him a glass of wine. “To the victor,” he said. Skorzeny drained the glass and accepted the Italian surrender. The Duce had been freed in about 10 minutes. Now came the challenge of getting him off the mountain.

With Mussolini and Otto Skorzeny stuffed into the small Fieseler Fi 156 “Storch”—the pilot taking off the overloaded aircraft in just 250 feet. Image courtesy of author’s collection.

With Mussolini and Otto Skorzeny stuffed into the small Fieseler Fi 156 “Storch”—the pilot taking off the overloaded aircraft in just 250 feet. Image courtesy of author’s collection.

Meanwhile, at the bottom of the mountain, Maj. Mors troops had captured the cable car station after a short firefight. Two Italians were killed, and two were wounded. Forty minutes later, Mors had taken the cable railway to the hotel and greeted Mussolini. The raid commanders decided that it would be too risky to take Mussolini out by car, so they opted to take him out via small plane—a Fieseler Fi 156 “Storch”, noted for its short takeoff and landing capabilities. Originally, a Focke-Achgelis Fa 223 helicopter had been detailed for this possibility, but the early helo broke down and could not be used.

The Storch pilot was Heinrich Gerlach, who landed his aircraft in just 100 feet, and later took off with Mussolini and Skorzeny on board in about 250 feet of rock-strewn runway. The Storch was not made to accommodate two passengers, both weighing more than 200 pounds. Ultimately, it was one of the most dangerous takeoffs and flights of the war. Skorzeny and Mussolini continued their journey, flying in a Heinkel He 111 bomber and reaching Vienna by the evening. By September 14, Duce was meeting with Hitler at the “Wolf’s Lair” in the forest east of Rastenburg.

“The Most Dangerous Man In Europe:” A portrait of Otto Skorzeny. The dueling scar came from his days as a fencer at the Technical University of Vienna. Polish National Archives photograph.

“The Most Dangerous Man In Europe:” A portrait of Otto Skorzeny. The dueling scar came from his days as a fencer at the Technical University of Vienna. Polish National Archives photograph.

By September 18, Mussolini made his first public address to the Italian people since his rescue. Hitler quickly installed him as the leader of the Nazi puppet state, the “Italian Social Republic” (RSI), with its headquarters near Brescia in north-central Italy. The SS controlled every aspect of the RSI, and consequently almost every aspect of Mussolini’s life. His escape from Allied captivity brought only a short moment of relief—the Duce’s remaining days were spent under Hitler’s thumb. In an interview conducted during January 1945, Mussolini stated: "Seven years ago, I was an interesting person. Now, I am little more than a corpse." On April 28, 1945, he was shot by Italian communist partisans as he attempted to escape into neutral Switzerland.

As for Skorzeny, the Allies soon branded him “the most dangerous man in Europe.” His fame and reputation continued to grow until the end of the war. After two years of internment, Skorzeny was acquitted on war crimes charges at the 1947 Dachau Trials. He later escaped from another internment camp in July 1948 and eventually landed in Spain.

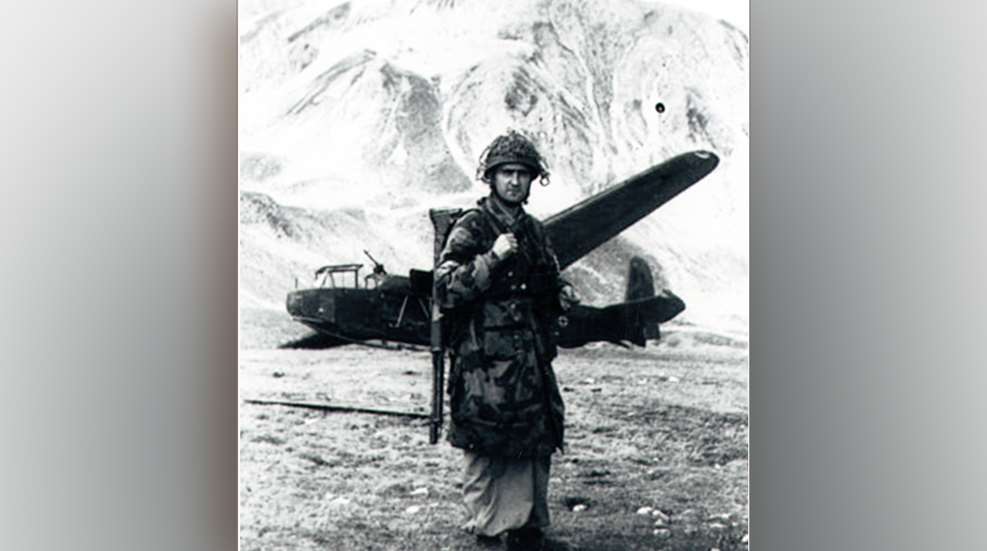

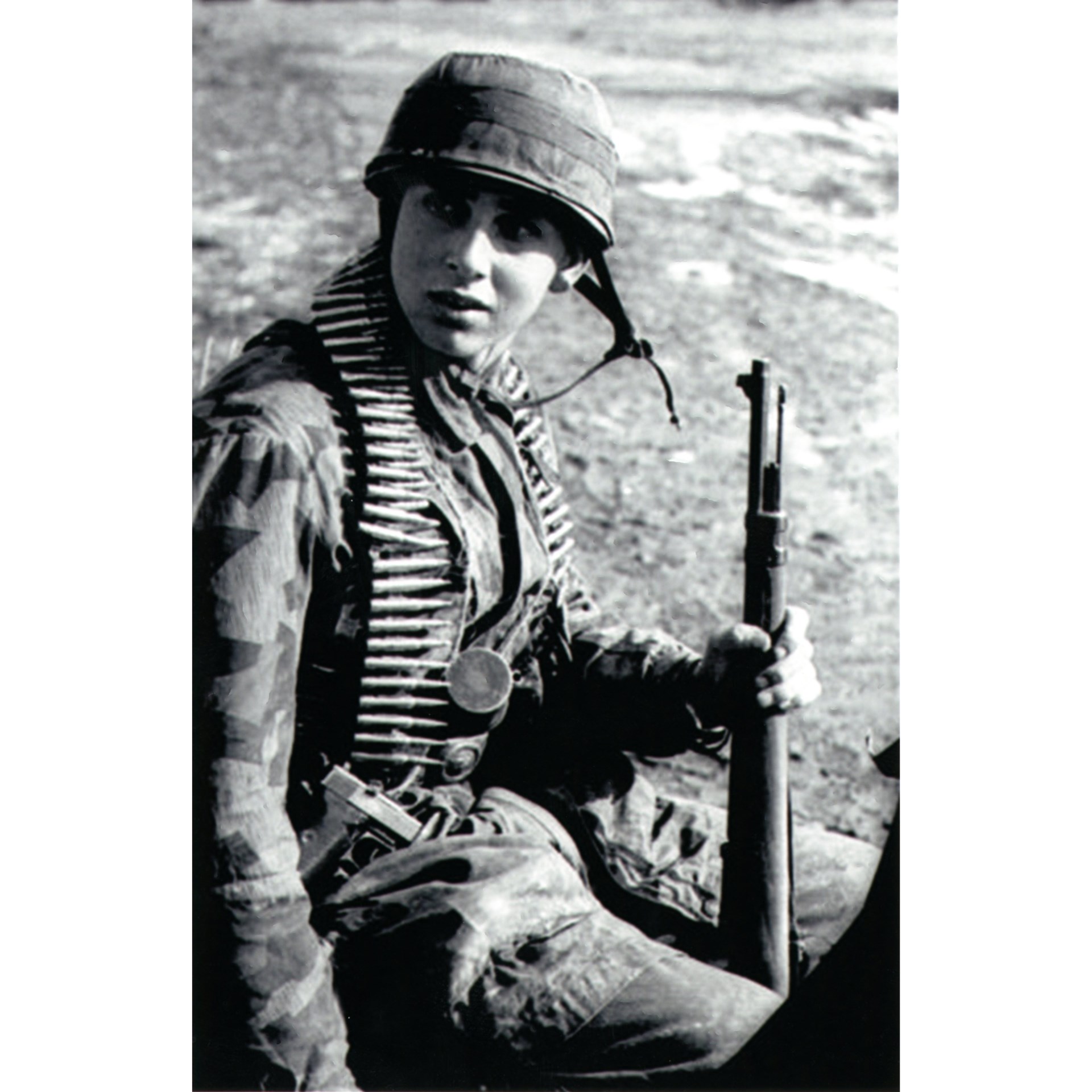

A heavily armed young paratrooper on the Gran Sasso raid. He carries a Karabiner 98k Mauser rifle (7.92 mm) and a Walther P38 pistol (9 mm), along with a belt of 7.92 mm ammunition for his squad’s MG34 or MG42—normally, the squad carried about 1,800 rounds of ammo between them to support the MG as their base of fire. Note that he also carries the Stielhandgranate 24. Image courtesy of author’s collection.

A heavily armed young paratrooper on the Gran Sasso raid. He carries a Karabiner 98k Mauser rifle (7.92 mm) and a Walther P38 pistol (9 mm), along with a belt of 7.92 mm ammunition for his squad’s MG34 or MG42—normally, the squad carried about 1,800 rounds of ammo between them to support the MG as their base of fire. Note that he also carries the Stielhandgranate 24. Image courtesy of author’s collection.

Intrigue was never far from Skorzeny, and he was linked to post-war Nazi groups, the CIA and even Israel’s Mossad. Along the way, he worked as a military advisor to the Egyptian government during the early 1950s, as well as the Perón government in Argentina. During the 1960s, he set up a mercenary organization, the Paladin Group, in Spain. He died from lung cancer in Madrid in July 1975.

The Combat Debut Of The FG42

During the successful, but ultimately costly German paratroop assault on Crete (May 20 to June 1, 1941) the Fallschirmjager learned a painful lesson about infantry firepower. At that time most German paratroopers jumped into combat armed only with a pistol—their 98k rifles and MG34s parachuted down in separate containers. Only 25 percent of the German paratrooper force came down with a MP40 submachine gun ready to use. In the critical early moments of the parachute assault, most of the German force was at a serious firepower disadvantage. This was particularly evident on Crete, as even the hodge-podge Allied defense force had sufficient firepower to inflict heavy casualties on the German airborne invaders.

U.S. Ordnance considered the FG42 to be the most desirable of the late-war German “assault rifles,” and the gun had significant influence on post-war U.S. designs. Springfield Armory photograph.

U.S. Ordnance considered the FG42 to be the most desirable of the late-war German “assault rifles,” and the gun had significant influence on post-war U.S. designs. Springfield Armory photograph.

The Luftwaffe Weapons Branch set out to develop a “universal weapon” for paratroopers. Chambered in 7.92x57 mm, and capable of selective fire, it would replace the bolt-action 98k rifle, the MP40 submachine gun, and the MG34 general-purpose machine gun. After some development of the firearm, Hitler cooled on the overall concept of airborne assaults, but Luftwaffe Reichsmarschall Goering intervened, and the FG42 project remained alive.

The FG42’s design allowed the user to top off an attached magazine. This FG42 was captured in Italy during October 1943. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration photograph.

The FG42’s design allowed the user to top off an attached magazine. This FG42 was captured in Italy during October 1943. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration photograph.

The innovative Fallschirmjägergewehr 42 featured a pistol grip, bipod and flash hider, and it could also mount a small telescopic sight. It was gas-operated and used a rotating bolt, firing from a closed bolt when in semi-automatic mode, and from an open bolt (for better cooling) when firing in full-auto. The initial model (informally called “Type I”) cycled at a lively 900 r.p.m. Later variants toned down the cyclic rate to about 750 r.p.m. On full-auto, the recoil, barrel climb and muzzle blast were severe—and the side-mounted 20-round box magazine was quickly drained. Even so, the select-fire capability was still welcome, although the troops were advised to use full-auto only in an emergency.

Fallschirmjager after disarming Italian troops after the Italian surrender to the Allies, September 1943. The paratrooper in the foreground carries the new FG42. Image courtesy of author’s collection.

Fallschirmjager after disarming Italian troops after the Italian surrender to the Allies, September 1943. The paratrooper in the foreground carries the new FG42. Image courtesy of author’s collection.

The FG42 first appeared in the Gran Sasso raid, and during the September 1943 “Operation Asche” to pacify the Italian military. Of all the German firearm designs in the latter part of World War II, U.S. Army Ordnance considered the FG42 to be the best, by far—particularly due to the gun’s use of the standard 7.92 mm cartridge.

American troops encountered the German paratrooper rifle in small amounts during the Italian campaign, and then in greater numbers during the fighting in Normandy. The German 2nd Parachute Division used the largest amount of the FG42s issued, and this unit was active in Normandy and Brittany, particularly near Carentan, St.-Lô and in the defense of Brest. The FG42 was never built in great numbers, and only about 7,000 were made by the end of the war. Despite the low production numbers, the FG42 made a powerful impression. There is ample evidence to suggest that the FG42 was influential in the development of the US M60 machine gun—designed in the early 1950s and still in use around the world today.