For several decades prior to the adoption of the Model 1903 Springfield rifle, the U.S. Army issued its U.S. Cavalry a carbine version of the standard U.S. Infantry rifle. The last official U.S. military carbine based on the standard infantry rifle was the Model 1899 .30-40 Krag, which had a 22" barrel as compared to the Model 1898 Krag rifle’s 30" barrel.

When the Model 1903 Springfield was in development, it was decided to equip the new rifle with a 24" barrel that was intended to be a compromise between the shorter cavalry carbine and the longer infantry rifle. Both the infantry and cavalry were generally pleased with the new rifle, and the concept of separate arms for the two branches of the Army was over.

Nonetheless, there was still a fondness for the carbine in the minds of some of the former cavalrymen, who appreciated its light weight and handiness. There were two prototype carbine versions of the Model 1903 Springfield rifle fabricated in 1921 by Springfield Armory for testing and evaluation, but the concept never went beyond the prototype stage.

When the M1 Garand rifle was adopted in 1936, it had approximately the same overall length as the M1903, which made it suitable for issue to both infantry and cavalry units. Such was the case until America’s entry into World War II, when the concept of a shorter M1 rifle was considered.

Although the .30-cal. M1 carbine had been adopted in 1941, it was an entirely different category of arm, and it was not designed, nor intended, to fulfill the same role as the M1 rifle. The light and compact semi-automatic M1 carbine lacked range, accuracy and “stopping power” compared to the M1 Garand. As World War II progressed, it was envisioned that a shorter version of the M1 rifle would combine the Garand’s power and accuracy with the compactness of the M1 carbine.

The Jan. 20, 1944, Springfield Armory “Monthly Report of Progress on R&D Projects” stated that a modified short-barrel Garand rifle, weighing about 1 lb., 3 ozs., less than a standard M1, was fabricated by the 93rd Infantry Division and tested by the Infantry Board.

It was recognized that such an arm might be particularly valuable for paratroopers, as it was more powerful than the carbines and submachine guns currently in use. Preliminary testing revealed it had excessive recoil and muzzle blast, but it was recommended that it be developed further. The Infantry Board directed Col. Rene Studler to proceed with the project.

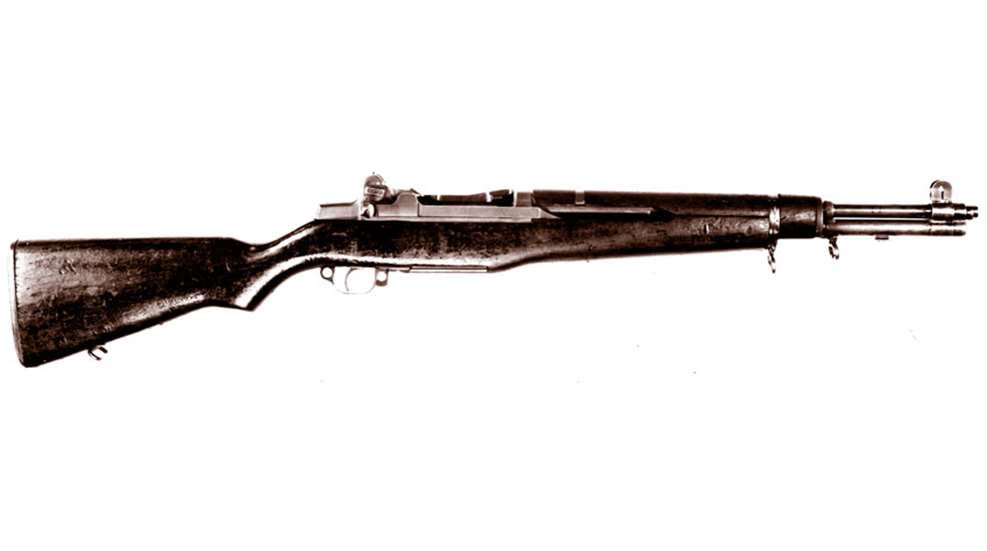

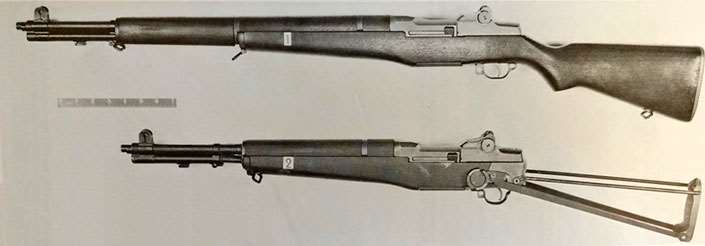

The task was assigned to Springfield Armory, and John C. Garand began work in January 1944. The resultant experimental arm, designated as the “U.S. Carbine, Cal. 30, M1E5,” was fitted with a specially made 18" barrel (not a shortened standard M1 rifle barrel) marked “1 SA 2-44” and a pantograph metal stock that folded neatly underneath the rifle. The receiver was marked “U.S. CARBINE/CAL. .30 M1E5/SPRINGFIELD/ARMORY/1.” It is interesting to note that it was designated as a carbine and not a rifle.

Other than the folding stock, the basic M1 rifle was essentially unchanged with the exception of the short barrel, a correspondingly shortened operating rod (and spring) and the lack of a front handguard. The overall length was 37½" and it weighed approximately 8 lbs., 6 ozs.

The M1E5 “Garand Carbine” was tested at Aberdeen Proving Ground in May 1944. It was determined that while accuracy at 300 yds. was on a par with the standard M1 rifle, recoil, muzzle blast and flash were excessive. It was recommended that a pistol grip be installed, which was done for subsequent testing.

Photos of the M1E5 in stocks with and without the pistol grip exist, which might suggest there were two different models, but this was not the case. The folding stock had been repaired several times and it proved to be rather uncomfortable when firing. Work began on a modified folding stock, designated as the “T6E3,” to improve the deficiencies found in the original pattern, but it was not fully developed.

The M1E5 suffered from the “compromise syndrome,” as it required a trade-off between compactness and performance. It was indeed more compact than the standard Garand rifle, but the short barrel made it an unpleasant gun to fire—and the advantages were not judged to be sufficient to offset the disadvantages. Further development of the M1E5 was suspended as other projects at Springfield, such as the selective-fire T20 series, were deemed to have a higher priority. Only one example of the M1E5 was fabricated for testing, and the gun resides today in the Springfield Armory National Historic Site Museum.

Despite the concept being shelved at Springfield Armory, the idea of a shortened M1 rifle was still viewed as potentially valuable for airborne and jungle combat use. Particularly in the Pacific Theater, there was widespread dissatisfaction with the M1 carbine’s range, power and foliage-penetration (“brush-cutting”) capability. The Ordnance Dept. was not responsive to these complaints coming in from the Pacific and maintained that the M1 rifle and M1 carbine each filled a specific niche.

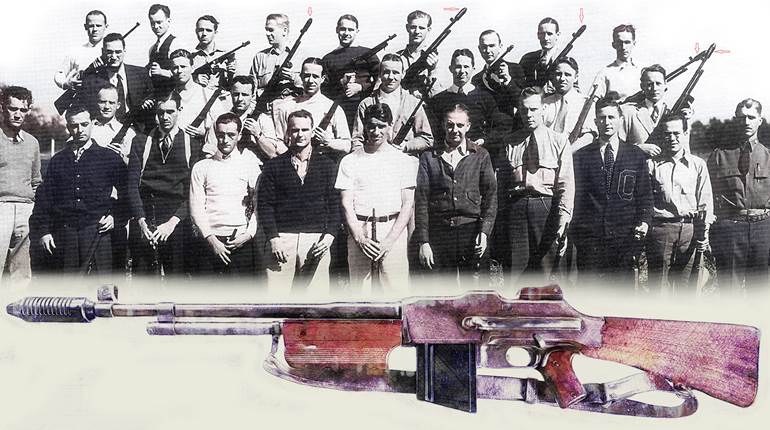

Nonetheless, by late 1944 the Pacific Warfare Board (PWB) decided to move forward with the development of a shortened M1 rifle. Colonel William Alexander, chief of the PWB, directed an Army ordnance unit of the 6th Army in the Philippines to fabricate 150 rifles in this configuration for testing. Since the previous M1E5 project was not widely disseminated, it is entirely possible that the PWB may not have been aware of Springfield Armory’s development of a similar rifle, and conceived the idea independently.

Some of the shortened M1 rifles were field-tested in October 1944 on Noemfoor Island, New Guinea, by an ad hoc “test committee,” which included three platoon leaders of the 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR) Combat Team. While the members of the test committee liked the concept of the short M1 rifle, it was determined that the muzzle blast was excessive and was compared to a flash bulb going off in the darkened jungle. The conclusion of the test report stated that the shortened rifle was “totally unsuitable for a combat weapon.”

Even while the shortened M1 rifles were being evaluated by the 503rd PIR, two of them, Serial Nos. 2291873 and 2437139, were sent to the Ordnance Dept. in Washington, D.C., by special courier for evaluation. One of these rifles was then forwarded to Springfield Armory. The guys at Springfield must have felt a touch of déjà vu, as the rifle was very similar to the M1E5 built by the armory and tested at Aberdeen several months earlier.

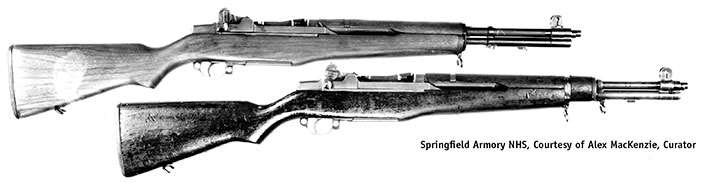

The major difference was that the PWB rifle retained the standard M1 rifle wooden stock rather than the M1E5’s folding stock. The M1s shortened in the Philippines under the auspices of the PWB had been well-used prior to modification, and the conversion exhibited rather crude craftsmanship, including hand-cut splines on the barrel.

Upon receipt of the PWB rifle, Springfield Armory’s Model Shop fabricated a very similar shortened M1 that was designated as the “T26.” One of the more noticeable differences was that the shortened PWB rifle had a cut-down front handguard (secured by an M1903 rifle barrel band), while the T26 rifle was not fitted with a front handguard. It had been determined that the full-length stock was superior to the M1E5’s folding stock, so the T26 used a standard M1 rifle stock.

It is sometimes claimed that Springfield Armory simply put the existing M1E5 action into an M1 stock and dubbed it the T26. This was not the case, as the T26 did not use the M1E5’s purpose-made (and marked) receiver, but was made with a standard M1 rifle receiver and newly made, specially modified parts.

Regardless, it is a bit curious that the Ordnance Dept. decided to go to the trouble of having Springfield Armory make up another shortened Garand for additional testing when the M1E5, which differed primarily in the type of stock, had been thoroughly tested several months previously with less than spectacular results.

The PWB rifle, Serial No. 2437139, and Springfield Armory’s T26 were sent to Aberdeen Proving Ground (APG) on July 26, 1945, for testing. The APG report related that a standard M1 rifle, Serial No. 1,032,921, was the “control” rifle to which the shorter rifle was compared during the testing. The results mirrored those of the M1E5’s previous testing. As related in the test report:

“The rifle tested was a standard cal. .30 M1 with barrel shortened approximately six inches. This alteration was accomplished in the Philippine Islands by an Ordnance Maintenance Company and the rifle was delivered to the Chief of Ordnance by a USAFFE Board representative for the test.

“The object of the test was to compare, by observation, the muzzle flash, smoke and blast of the shortened M1 rifle, with and without the flash hider, to that of the standard rifle.

“Conclusions:

“The muzzle flash of the modified rifle, with and without flash hider, was approximately eighty (80) percent greater than the flash of the standard rifle.

“The muzzle smoke of the modified rifle, with and without the flash hider was equivalent to that of the standard rifle.

“The muzzle blast of the modified rifle, with and without flash hider, was approximately fifty (50) percent greater than that of the standard rifle.

“The recoil of the modified rifle was noticeably heavier than that of the standard rifle.”

In addition to the increased recoil and muzzle flash/blast, functioning problems related to the shortened operating rod and the location of the gas port in the shortened barrel were noted during the testing. The fact that the gas port was positioned closer to the chamber as compared to the standard M1 rifle resulted in increased port pressure, which was detrimental to proper functioning.

It should be noted that only the shortened PWB rifle, and not the T26, was discussed in the Aberdeen test report. It is reported that the T26 rifle was damaged during the testing, which is presumably why it was left out of the final report. The ultimate disposition or whereabouts of the T26 rifle are not known, although it has been speculated that it was salvaged for parts.

Somewhat inexplicably, despite the less-than-stellar results of the previous testing, including the 503rd PIR test committee’s conclusion that the modified rifle was “totally unsuitable as a combat weapon,” the concept was still of interest inasmuch as approval was forthcoming for procurement of 15,000 shortened M1 rifles. As related in the “Record of Army Ordnance Research and Development, Vol. 2”:

“In July of 1945, the Pacific Theater requested that they be supplied with 15,000 short M1 Rifles for Airborne use. A design of a short M1 Rifle was delivered by a courier from the Pacific Warfare Board. A comparative study of the sample short M1 Rifle and the M1E5 (a 1944 program to develop a short-barreled, folding stock M1, that was dropped as being of low priority) indicated a definite preference for the M1E5 action equipped with the standard stock; the rifle so equipped was designated as T26. A study by Springfield Armory resulted in a tentative completion schedule of five months for the limited procurement of 15,000 T26 Rifles; however, with the occurrence of V-J day on 14 August 1945 this requirement was dropped.”

Since none of the 15,000 rifles was manufactured, there was only one T26 ever made. The M1 rifles shortened by the ordnance unit of the 6th Army in the Philippines apparently never had an officially assigned nomenclature. For lack of the better term, “Pacific Warfare Board Rifle” is undoubtedly the most appropriate designation for these rifles, albeit an unofficial one.

One of the PWB rifles, Serial No. 2291873, currently resides in the Springfield Armory Museum. The other PWB rifle, which was tested at Aberdeen in July 1945, Serial No. 2437139, has been in the West Point Museum (Catalog No. 19657) since it was transferred there by the Ordnance Dept. shortly after World War II.

According to West Point Museum officials, the only modification to the rifle since its testing by Ordnance was the substitution of the later T105E1 rear sight assembly in place of the original “locking bar” rear sight. The PWB rifle in the Springfield Armory collection appears to remain in its original configuration. It is interesting to note that at least one Springfield Armory archival photo (1964 vintage) exists that erroneously identifies the PWB Rifle in the museum’s collection as a “T26.”

There are still a number of unanswered questions regarding these rifles beyond the fate of the original T26. For example, it has not been confirmed beyond the shadow of a doubt how many of the rifles were actually fabricated in the Philippines as ordered by the PWB beyond the two known examples. While not stated one way or the other, it may be possible that the PWB waited to get word from Washington whether or not the concept met with Ordnance’s approval before proceeding with modification of the entire batch of 150 rifles.

The above-referenced report of the field testing of the short rifles by the 503rd PIR indicates that at least some additional rifles, beyond the two sent stateside, were produced. In any event, the number of shortened M1 rifles actually made during World War II as directed by the PWB almost certainly would have been no more than 150. The fact that no convincingly documented examples of the PWB-shortened M1 rifles are known to exist (other than the two mentioned above) seems to lend credence to the contention that few were actually fabricated.

It has been postulated, however, that the dearth of existing specimens can be explained because the shortened rifles were destroyed or re-converted to standard M1 rifle configuration after the “Garand Carbine” program was dropped. Unless further documentation is forthcoming, this will probably remain the subject of conjecture and debate.

Some claim to have run across, or own, one of these fascinating arms, but since converting a standard M1 to PWB/T26 configuration is not an overwhelmingly difficult gunsmithing task, and since there is no known roster of PWB rifle serial numbers, confirming the provenance of such a rifle is virtually impossible. There are a number of known fakes around including one with impressive, but totally bogus, “Pacific Warfare Board” markings on the receiver. The odds of one of the PWB rifles surviving and being smuggled home are all but nil.

Nevertheless, hope springs eternal and a number of individuals are certain they have a genuine example. Without some sort of convincing documentation, which almost certainly will not exist because any PWB rifle “on the loose” would be stolen government property, such a claim must be approached with much skepticism. A good rule of thumb to remember is: If it’s not in the Springfield Armory or West Point museums, it’s not a genuine Pacific Warfare Board rifle.

The shortened M1 rifle was one of those things that looked good in theory but didn’t work out so well in actual practice. With the conclusion of World War II, the U.S. military closed the chapter on the concept of a “Garand Carbine.”

The “Tanker Garand” Emerges

Despite its rejection by the American military, the idea of a Garand rifle shorter than the standard M1 was later resurrected in the civilian sector. The genesis of these rifles began in the early 1960s when some enterprising individuals acquired large quantities of surplus military firearm parts, including a significant number of M1 rifle receivers that had been “demilled” by torch-cutting.

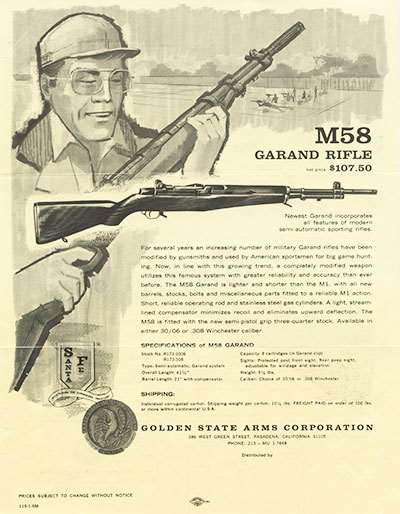

Among the most notable of these was Robert E. Penney, Jr. Penney and his associates began to produce rifles, primarily standard-length M1 Garands, for the civilian market using these surplus parts, including some of the welded and re-machined torch-cut receivers. Examples were made in both .30-’06 Sprg. and .308 Win.

Penney was apparently aware of the World War II-era experimental shortened M1 rifles and decided a rifle in such a configuration would be a good addition to his company’s product line. The imaginative term “Tanker Garand” was coined for these rifles, presumably to give the impression (totally erroneous) they were military arms made for use in tanks. Despite being a fantasy appellation lacking any basis in reality, the name stuck.

Since genuine military M1 rifles were not readily available to civilians during this period, the ersatz Garand rifles, including the novel “Tankers,” sold relatively well. When the supply of the surplus components began to be depleted, Penney was faced with the prospect of manufacturing new parts. Such items as receivers, bolts and operating rods would have been prohibitively expensive to produce. Faced with this daunting prospect and declining health, Penney stopped manufacturing and sold the company.

While he was one of the pioneers in the field, it should not be inferred that Penney’s firm was the only one to make the so-called Tanker Garands. Several commercial firms, and even some individual gunsmiths, have continued to turn out similar arms to this day, either using existing G.I. M1 receivers, “demilled” receivers welded back together or newly made cast receivers. The workmanship can vary from extremely professional to downright shoddy.

Some people are enamored with the neat-looking little rifles, but this ardor often cools a bit when a few rounds are fired and the muzzle blast and recoil are experienced. Many owners of “Tanker Garands” found out what the Ordnance Dept. and the 503rd PIR test committee discovered in 1944-1945, and decided to become former owners when firing their pet guns proved to be less fun than originally imagined.

Nonetheless, some civilian shooters are not particularly bothered by the increased muzzle blast and recoil, and they continue to enjoy the neat little guns. In any event, these commercially shortened Tanker Garand rifles are not, and never were, military arms but are an interesting part of the fascinating story of the Garand.

While the concept of a “Garand Carbine” never went beyond the testing stage by the American military, it nevertheless illustrates how our armed forces continued to seek ways to improve the arms issued to our fighting men during the greatest conflict known to mankind.