This article, "Snipers—Specialists in Warfare," appeared originally in the July 1967 issue of American Rifleman. To subscribe to the magazine, visit the NRA membership page here and select American Rifleman as your member magazine.

It's a long way from Camp Perry to Vietnam. Or is it?

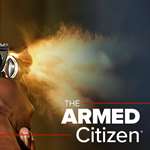

Maj. William W. McMillan , Jr., USMC, National Pistol Champion at Camp Perry in 1957, two-time Olympic Gold Medal winner, and five-time winner of the Marine Corps' Lauchheimer trophy, has been operating a "jungle rifle range" to teach Marines how to stay alive in Vietnam.Throughout history, handfuls of excellent marksmen have turned the course of battles and the outcome of wars. They have picked off an in credible number of generals and even more of other ranks. From Florence and Rome of the Renaissance to the jungles of Vietnam, a single sharp rifle crack has been the calling card of the sniper. Now the ranges are longer, the certainty of a hit is stronger, and the weapons are more modern. But the ultimate element—the rifleman—remains the same.

Almost ever since the start of accurate riflemanship, precise shooting has been an art. Two of its earliest practitioners, in fact, were famous artists. As early as 1520 A.D., Leonardo Da Vinci, the Renaissance genius who in addition to all else was a skilled marksman, picked off enemy soldiers from the walls of besieged Florence with a rifle of his own design at ranges up to 300 yds.

Benvenuto Cellini—artist, sculptor, silversmith and goldsmith—helped to lift the siege of Rome in 1527. While defending the Holy City for Pope Clement VII, by his own account he fired the shot that killed the enemy commander, the Constable de Bourbon. Perhaps Cellini's greatest appreciation of marksmanship, however, was as a relaxation.

His autobiography says:"...I will give but one particular, which will astonish good shots of every degree; that is, when I charged my gun with powder weighing one-fifth of the ball, it carried two hundred paces point blank. My natural temperament was melancholy, and while I was taking these amusements, my heart leaped up with joy, and I found I could work better and with far greater mastery than when I spent my whole time in study and manual labor."

Cellini followed Da Vinci by only a few years in the same post-that of supervising the defense of Florence, the showcase of European civilization. While all this was taking place, America was just being discovered, explored and conquered with the aid of firearms. Spanish explorers did not need to worry too much about marksmanship against poorly equipped Indians, but when the time came that white men fought each other, marksmanship once again resumed a leading role.

A British historian says: "General Braddock's disastrous defeat in 1755 with a loss of nigh 75-percent of his force from the rifle fire of the French Canadians and Indians may be taken as the turning point in our military history as regards marksmanship."

The First British Snipers

The British then enlisted people who knew how to fight that kind of war. As the result, the first "snipers" in the British Army were Americans. The 60th Royal Americans accompanied British armies on several campaigns following Braddock's defeat.

During the American Revolution, British Gen. Fraser was mortally wounded from several hundred yards by one Tim Murphy of Morgan's Rifles, sniping from a tree. The ensuing confusion permitted the Americans to encircle that portion of the British line and force a retreat to Saratoga, where Gen. Burgoyne eventually surrendered.

In the War of 1812, a triple-headed British thrust to cut up the United States was stopped when American riflemen killed two of the commanding generals (Pakenham at New Orleans and Ross at Baltimore) and wounded the third (Prevost at Plattsburgh).

A seagoing sniper, firing from the rigging of the French man-of-war Redoubtable upon the quarterdeck of H.M.S. Victory, Oct. 21, 1805, accounted for one of the greatest naval commanders of all time. The bullet hit Admiral Horatio Nelson in the spine, wounding him mortally at the moment of his great triumph in the Battle of Trafalgar.

In the Peninsular War between the British and French during Napoleon's time, the 60th, now English and renamed the King's Royal Rifles, saw service in Spain. Marshal Soult, the French commander-in-chief, soon wished they hadn't.

In a letter to the Minister of War in September 1813, the marshal explained:

"There is in the English Army a battalion of the 60th, consisting of ten companies... This battalion is never concentrated, but has a company attached to each infantry division. It is armed with a short rifle; the men are selected for their marksmanship; they perform the duties of scouts, and in action are expressly ordered to pick off officers, especially field or general officers... This mode of making war and of injuring the enemy is very detrimental to us; our casualties in officers are so great that after a couple of actions the whole number are usually disabled. I saw, yesterday, battalions whose officers had been disabled in the ratio of one officer to eight men! I also saw battalions which were reduced to two, or three officers, although less than one-sixth of their men had been disabled."

Thus the shoe which had kicked Gen. Braddock so painfully was now on the other foot. But it was to change feet again and again throughout the history of warfare as first one side, then the other, learned the value of accurate riflemen employed as snipers.

Civil War Snipers

On one hot July afternoon at a place called Gettysburg, Confederate snipers using special heavy rifles killed two Union generals, wounded a third and killed a colonel, plus a number of lesser officers who were on the Round Tops. During the war as a whole, Federal snipers killed six Confederate generals.

During the Boer War in South Africa, young British Tommies going off to battle were advised, "Stay away from officers and white rocks." Why? Because the Boers, keen marksmen, picked off officers and used white rocks for sighting in.

Sniping became a methodical plan of warfare in World War I, according to the British sniping authority , Maj. H. Hesketh-Prichard, when the German Duke of Ratibor put the Kaiser's army into the sniping business wholesale. The good duke, who apparently had access to official records, "...collected all the sporting rifles in Germany and sent them to the Western Front," Hesketh-Prichard reports.

He estimates that the Germans had 20,000 rifles equipped with telescopic sights by the end of 1914, and that the British lost hundreds of officers before realizing how serious a threat the snipers were. Again, the shoe was on the other foot, kicking painfully.

British Countersniping in World War I

British snipers, organized and trained because of the German success, later accounted for as many as 100 of the enemy apiece. They countered the German sniping by using two-man teams. Where were these recruited? Largely among hunters, including Canadians and Australians. The rifle of one Canadian trapper credited with picking off at least 125 Germans was made part of a wartime exhibit in London.

But aside from specific sniper training, the Allied armies of World War I did little to improve individual marksmanship. Many military thinkers concluded that modern wars would be fought largely with machine guns, grenades, mortars and heavier weapons. One who felt otherwise was Gen. John Pershing, commander-in-chief of the A.E.F. in France.

"The armies on the Western Front in recent battles that I bad witnessed," Pershing commented, "had all but given up the use of the rifle... Numerous instances were reported in the Allied armies of men chasing an individual enemy throwing grenades at him instead of using the rifle. My view was that the rifle and bayonet still remained the essential weapons of the infantry."

But sniper training was something else. Even among line troops there were exceptions. The Marines in France were meeting German attacks with effective rifle fire that began when the enemy was 800 yds. away. American equipment was being designed to provide accurate fire even farther away.

During the Second World War, many people referred to "snipers'' when they really meant ordinary rifle fire from infantry troops or just stray bullets from the direction of the enemy. An enemy soldier who fired at a specific target from more than 200 yds. away was often called a sniper, especially if he happened to be Japanese and was hidden in a tree.

By modern definitions, such troops with ordinary service arms are called sharpshooters at most, while a sniper has a special rifle, telescopic sights, special training and likely belongs to a separately organized sniper unit.

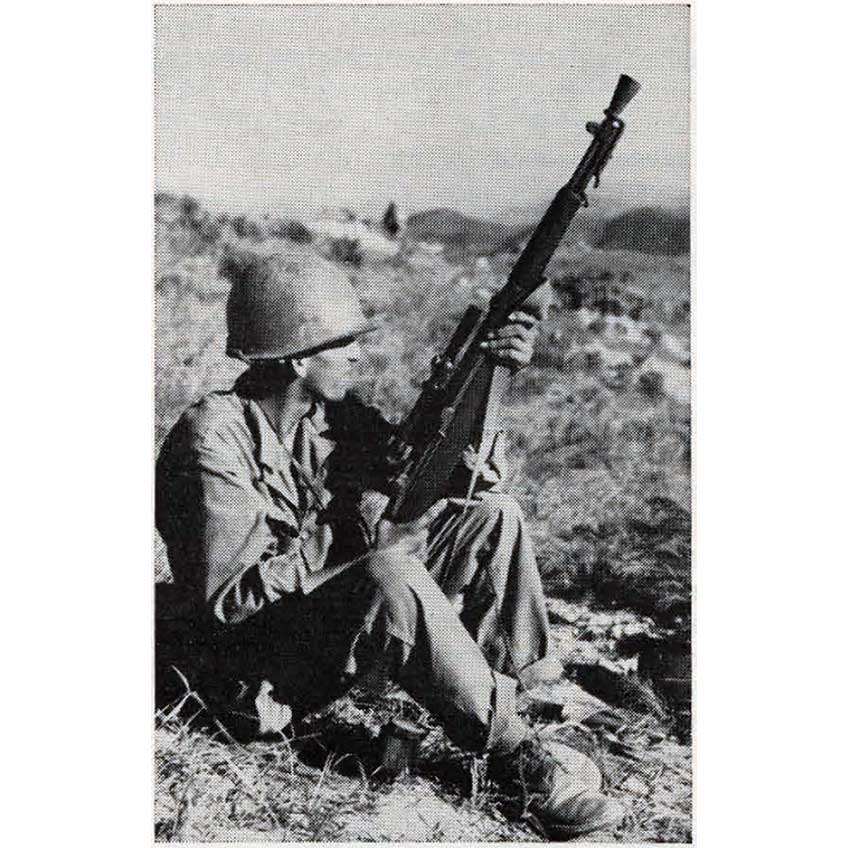

During the Second World War, most of the techniques developed during the First World War were used by snipers, such as 2-man team operation, camouflage , separate unit organization, telescopic sights, and so on. Each war added a little something, such as infrared "sniperscope" for relatively short-range night sniping at the end of the Second World War.

From the sniper's point of view, enemy generals seem to become more scarce as wars go by. What is probably the ultimate situation has come to pass in Vietnam, where the difficulty of distinguishing officers from privates led one U.S. officer to remark:

"When everybody is wearing black pajamas, who do you shoot? Even the North Vietnamese regulars who wear uniforms are not identified by rank. So all we can do is shoot the one who looks different in any way. Our snipers watch the enemy, and if we can see who is giving the orders, we shoot that one. Sometimes it's pretty difficult. If we see four Viet Cong who look identical, but three are wearing black sneakers and one is wearing white sneakers, we shoot the one wearing white sneakers."

Only if it is feasible to search the body for documents can snipers determine if their target was an officer. By the same token, determination of results is very difficult, and the sniper is not expected to confirm his results if his own safety is jeopardized.

One of the few confirmed hits with identification was that of a Chinese advisor shot out of a boat full of Viet Cong. He was taller than anyone else, was wearing a distinctive high-collared tunic and had a red star on his cap.

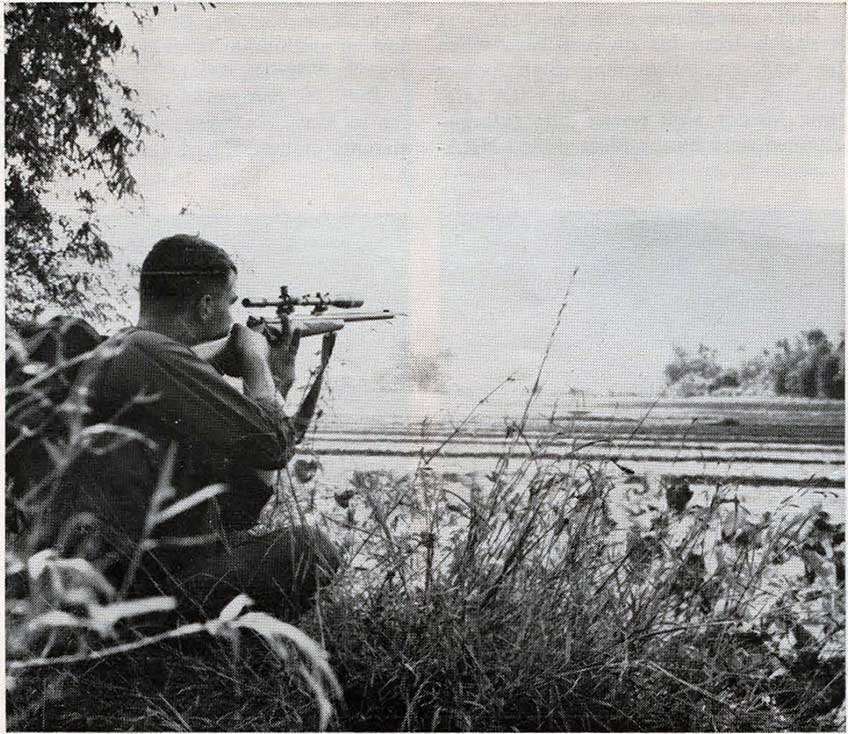

Strong emphasis on snipers in Vietnam is found in the Marine Corps, where two-man teams operate with considerable effectiveness.

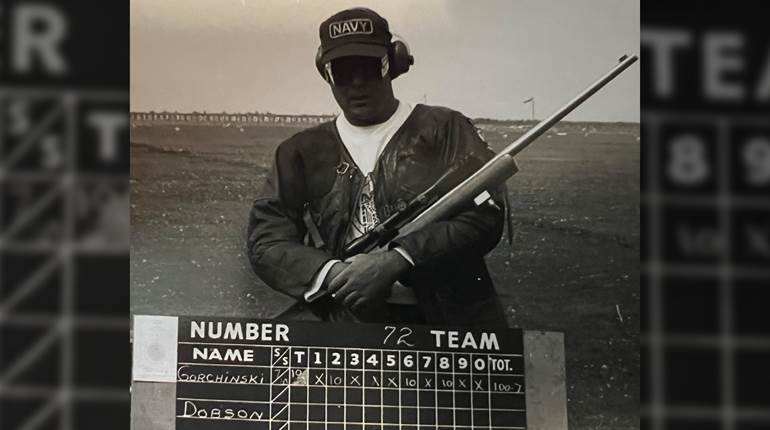

Several of the Army's competition shooters are now in Vietnam. Among them are Capt. D. W. Adams, winner of more than half a dozen smallbore matches at Camp Perry in 1966, includ ing the National Smallbore Prone Championship, and Capt. J. R. Foster, member of the winning Hercules Tro phy team at Camp Perry in the same year. Such officers are now serving primarily as unit commanders at present.

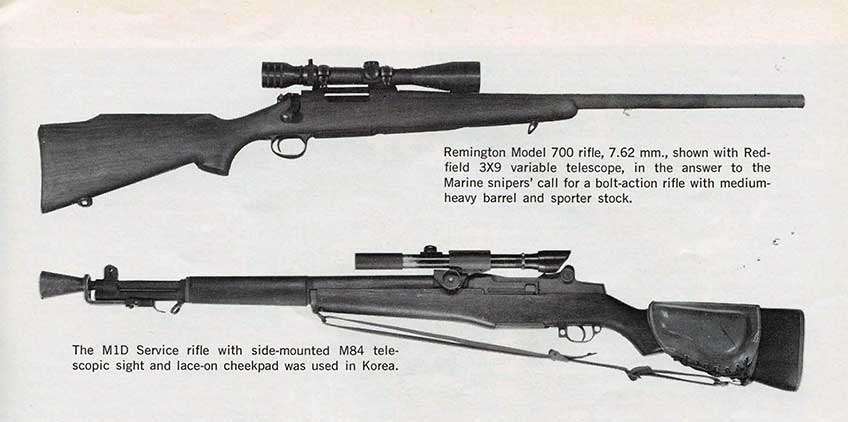

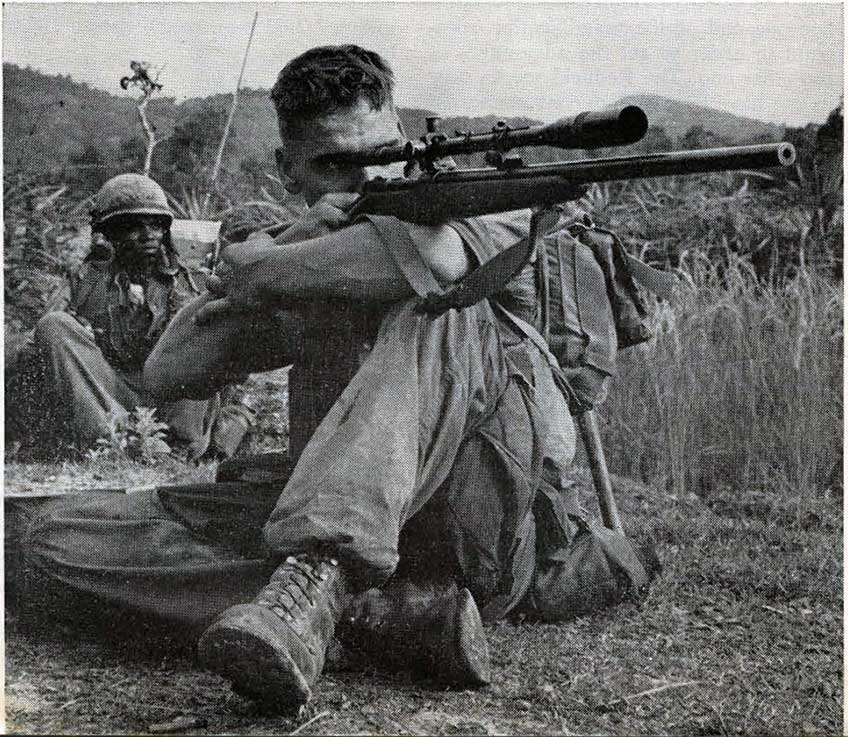

As related by Gen. Wallace M. Greene, Jr., commandant of the Marine Corps, in his address to the NRA Annual Members meeting, the Marines in Vietnam "...are equipped with binoculars for wide sweeps of their target area and with Remington Model 700 bolt action rifles. The rifle mounts a Redfield 3X9 power scope, and fires a 7.62 mm. cartridge.

Although this is becoming the standard equipment with many sniper teams, a large number of Winchester Model 70 rifles also are used, as well as Unertl 8X telescopic sights. The original Model 70s, which started out as the sole specialized armament of the Marine snipers, were from the 3rd Marine Division rifle team. When these turned out to be too few, more Model 70s were shipped out with heavy barrels and sporter stocks.

The 8X telescopic sight was chosen in WWII when it was teamed up with the '03 rifle. The scopes now used in Vietnam are the same scopes on newer rifles. Some of the snipers now in Vietnam were not yet born when the telescopic sights they use were employed in a different war. "In the early 1940s" says a Marine Corps spokesman, "we were advised that a Unertl 8X scope on the Winchester Model 70 was the best sniping combination, but the '03 was available in quantity, so we used it."

Later, efforts were made to get a suitable match rifle for Marine Corps rifle teams that would meet the NRA's weight limitations for such equipment in competition. The late Brig. Gen. George Van Orden, USMC, (Ret.), head of Evaluators, Ltd., went to Winchester and had some Model 70s made up with a heavy barrel on a sporter stock.

This rifle met the weight requirements (since changed by NRA) and also happened to be the same configuration which Brig. Gen. Van Orden had recommended for sniper use in the early 1940s. It was this configuration of the Model 70 which S/Sgt. Don L. Smith, USMC, used in 1953 to win the National Match Rifle championship at Camp Perry.

The rifle team of the 3rd Marine Division had been using the Model 70 with the heavy barrel and the heavy-marksman stock, in view of the changed weight limitations. When the need arose for more Model 70s, the rifles procured by Brig. Gen. Van Orden, including Smith's championship-winning rifle, were shipped out as supplemental equipment to Vietnam.

In addition to these two batches of Model 70s, some M1D service rifles with M84 side-mounted telescopic sights and lace-on cheek-pads were shipped to the Marines. Then the Marines went to Remington, buying enough Model 700s to equip the Marine Corps with its new Table of Organization for a 39-man sniper platoon to be part of each regiment.

The Remington Model 700s, in a manner similar to the Winchester Model 70s, are made up of standard components to Marine Corps specifications. The Marines wanted a bolt-action rifle with a medium to heavy barrel and a sporter stock.

There was no real reason to stay with Winchester, because the Model 70s used by the Marines were not the latest production models anyway, and no advantage would be gained as far as standardization of equipment was concerned. Like Winchester, Remington did not make a heavy-barreled sporter, but they made rifles with the necessary components, so they put the desired pieces together and came up with the Marines' sniper model.

According to the Marine Corps, there is no significance in the fact that the rifles are bolt-action types. In World War II, the German army actually preferred a semi-automatic rifle with telescopic sights for their snipers—not be cause of any increased accuracy, but because the autoloading feature required the sniper to move about less in his place of concealment.

The Marine Corps said it was seeking a sniper rifle, not a target rifle. To quote their definition:

"A target rifle is expected to put all its shots into a very small group after some adjustments to the sights. The sniper's rifle must put the first shot of any day into the same spot as the last shot of any other day. A free-floating heavy barrel allows this with very few adjustments. A sniper gets no sighting-in shots, and he doesn't intend to put 10 shots into the same target."

As for the current switch to the M16 rifle, the Marines have no plans for it in their sniper units so far, but have remarked that its accuracy is surprising. The firepower represented in the M16 is not required by the sniper unit's mission. The Marines seem to be guided by the philosophy: "Firepower usually means an increased number of misses per minute. Fifty misses are not firepower. One hit is firepower."

Whereas the 8X was selected in Second World War as the most desirable, and is still used in Vietnam, it is acknowledged by snipers that sometimes a lower-powered scope would be preferred. Some authorities on sniping, notably the British, prefer a 4X scope, but the Marines stick with the 8X.

The reason for the current changeover to the variable model is that 9X is available when needed, but occasionally in dim light, the brighter image afforded by 3X offsets the advantages of higher magnification.

Maj. William K. Hayden, USMC, assistant head of the Marksmanship Branch, G-3, at Marine Corps Head quarters (and a member of the Mayleigh Cup International Team in 1964 at Camp Perry) said the reports he has received from Vietnam indicate that the higher powers of the Redfield 3-9X scope are used more often than the lower powers.

By having the variable type, he said, it is unnecessary to sacrifice one end of the magnification spectrum in order to get the advantages of the other end. The Redfield scopes now in use have a rangefinder system to aid the sniper in range estimation, but snipers are still trained to estimate their own ranges.

Sniper Ammunition

There is often a recommendation made that a high-velocity varmint-type cartridge of relatively small caliber be used for sniping. But the Marine Corps argues against this, and the argument is convincing. Aside from the ease of supply afforded by using Service ammunition, there are other considerations.

Aspects such as trajectory, velocity and stopping power are only some of the more obvious reasons for sticking with the 7.62 mm. cartridge, since all these factors come out on the favorable side. But there is also a matter of noise. In any battle, it is not wise to have a distinctive-sounding weapon in the hands of a valuable man. If his rifle sounds just about like any other service weapon, he will probably be alive a lot longer.

The present cartridges used in Vietnam are excellent for their job by any standards, say the Marines. The 7.62 mm. cartridge, M118, uses the same long-range 173-gr. boat-tailed bullet found in the .30-'06 Sprg. M72 cartridge. This heavy bullet was originally designed to provide accurate long-range machine gun fire.

There is no 7.62 mm. Service cartridge using the 173-gr. bullet, but there is the M118 match cartridge which uses it and propels it at 2,550 f.p.s. The performance of this round as a sniper cartridge is attested to by its accuracy at 1,000 yds. The standard military 7.62 mm. round uses a 147 -gr. bullet.

Marine Sniper Platoons

The snipers are part of a 39-man platoon which is assigned to regimental headquarters as a supporting element similar to tanks or artillery. Each regiment in the Marine Corps, under the new table of organization, will have such a platoon. If a battalion or company commander needed one or more sniper teams, he would request them from regiment in the same manner as he requests other attached supporting elements.

Two Viet Cong several hundred yards out in front of his perimeter might be suspected by a company commander to be artillery observers, but calling mortars on them would be in effective unless the first round was a direct hit. An outgoing patrol might run into an ambush or at least cause the suspected observers to disappear. So the company commander might decide to ask regiment to send down a sniper team to deal with the Viet Cong.

The Marine Corps feels that organizing its snipers in this manner will ensure their most effective use and will make certain that the effects of the sniper program are fully known to appropriate commanders.

(At one time, the Army had a system whereby one outstanding marksman was designated the "sniper" of a squad, but this fits the modern definition of a sharpshooter more than that of a sniper with his special equ ipm ent, training, and organization.)

(The British concept of snipers leans more heavily toward the scouting aspect than does the Marine Corps concept, since the Marines have reconnaissance units for specific missions and the gathering of intelligence information is the job of all units, regardless of size or mission.)

The great majority of snipers in Vietnam have been men of much hunting experience, and many have been NRA members of long standing.

In the original 3rd Marine Division sniper unit, for example, the top-ranking seven enlisted men included one NRA Life Member and five other NRA members whose membership totaled 45 years—or an average of 9 years each. These same seven top-ranking enlisted men had hunting experience totaling 129 years, or an average of 18.5 years each, as well as competitive shooting experience totaling 106 years for an average of 15 years each.

For the entire 44-man sniper unit, the competitive shooting experience totaled 209 years, or an average of 4.75 years per man, as well as 367 years of hunting experience giving an average of 8.35 years per man. Ten of the 44 Marines did not list hunting among their shooting experience, and of the remaining 34, the average age was 24.4 years.

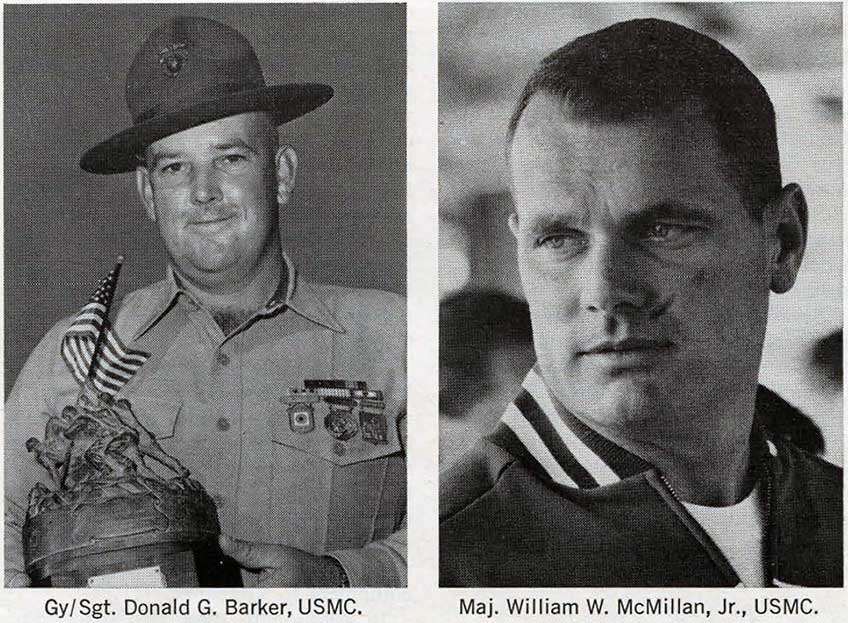

This is the kind of training and experience which makes snipers like Sgt. Carlos Hathcock and Gy. Sgt. E.R. England. With all that experience, when did they start?

Obviously, the higher-ranking members of the unit were the older and more experienced men, but even among the younger snipers, there appears a great deal of hunting and competitive shooting experience.

Hunting Experience Among Snipers

The youngest age at which any of the hunters began is 6 years, and the oldest starting age was 19, the average starting age for hunting being 13.5 years. The average hunting experience for the 34 Marines who listed it among their shooting training was about 11 years.

With this kind of background, it is small wonder that these men were selected as snipers. As the late NRA Executive Director, Maj. Gen. Merritt Edson, USMC (Ret.), said in an editorial in The American Rifleman in 1951: "It is not my intent to imply that the ability to shoot straight is the beginning and the end of national security. But it is that part of national security which affects the individual more than any other."

Sniping Between the Wars

It has been almost axiomatic that the end of a war also sees the end of any interest in snipers or sniper training by the military until the shoe suddenly appears on the other foot. The reasons seem to be:

1. Sniping is not a career field, so there are no "sniper colonels" to perpetuate the breed as there are infantry colonels or artillery colonels.

2. Sniping is necessarily surreptitious, so few line officers or troops know what snipers have. For example, if a sniper team eliminates enemy artillery observers, it is not likely that infantrymen will attribute the lack of enemy artillery to their own snipers.

3. Snipers have been so often mis employed that officers who have used snipers ineffectively often blame the poor results on the sniper concept itself.

4. With the usual reduction in armed strength after a conflict, the first units to be disbanded or downgraded are specialists appropriate for only one kind of warfare. Sniping does not seem to be recognized as a universally applicable tactic.

It has been noted that many aspects of the current Marine Corps sniper program follow closely on the lines laid out by military writers who spoke with authority on the subject following experience in the First and Second World Wars.

The Marines are using two-man teams, one man observing while the other fires; telescopic sights, a seemingly obvious advantage but one which was ignored for some time; great mobility, now that the helicopter has removed many limitations from a sniper's movement; experienced hunters and marksmen; the element of surprise far from a routine combat area; and, certainly not the least advantage, the most accurate rifle it is practical to employ.

Not only do snipers decimate the enemy's ranks slowly but surely, but the sniper's effect on enemy morale is great. When a man must walk around his own backyard in a half-crouch, he has been affected.

When asked if it was merely coincidence that the Marine Corps program so closely followed the often-repeated recommendations or if someone had carefully laid out a pattern of equipment and operation, a Marine spokesman said simply: "We read the books."