This SIG Sauer 130-gr. Controlled Expansion Tip bullet, fired from a 6.5 mm Creedmoor rifle, expanded well and drove far into a block of ballistic gelatin.

SIG Sauer took the long comprehensive view when it decided to manufacture its own ammunition in 2012. Keeping the industrial wheels turning at SIG’s firearm, suppressor and optics businesses requires a continual and substantial amount of ammunition, some of which presented a less-than-accurate account of the quality of SIG’s products. With its own ammunition, SIG could ensure quality control, support the introduction of new firearms and offer customers the whole shooting match, so to speak.

SIG started manufacturing Elite Performance Ammunition in a plant “pretty much in a Kentucky cornfield,” said Jason Imhoff, SIG’s director of ammunition engineering; however, the company’s ambitions quickly outgrew the Kentucky site.

In 2016, after Arkansas courted SIG with open arms, it moved into a 70,000 sq.-ft. building in Jacksonville. Growth rapidly increased with initially three, then 50 and now 168 employees manufacturing bullets, cases and extensive lines of handgun and rifle ammunition. Elite Hunter Tipped rifle ammunition and rifle cases for handloaders are two of SIG’s newest products to come from Jacksonville.

Elite Hunter Tipped

Elite Hunter Tipped ammunition joins SIG’s Varmint & Predator, Copper Hunting and Match Grade rifle ammunition. The polymer-tipped bullets are Sierra Tipped GameKing or GameChanger bullets made to SIG’s specifications, Imhoff said. The black copper-plating on the bullets is the most obvious modification. It provides corrosion resistance. Mainly, though, it looks cool. Tipped bullets are also constructed slightly wider at the hollow point, which is capped with a yellow tip—SIG’s color.

Tipped bullets have a boattail, and, together with a long taper to their ogive, deliver the highest ballistic coefficient of about any controlled-expanding hunting bullet of the same caliber and weight. The bullets are made with a gilding metal jacket that is progressively thicker toward the base and that surrounds a 3 percent antimony lead core. On contact with game, the polymer tip shears off to expose a pocket in the nose that instantly opens up to expand the lead core and peel back the jacket.

A giant mixing tank dominates a room at the SIG plant and is dedicated to forming blocks of ballistic gelatin that are stored at the correct temperature in refrigerators. SIG supplies ammunition to various government agencies that demand exact verification and visual proof of bullet penetration and expansion. The SIG folks have made and shot more than 6,000 gelatin blocks, gathering that information since setting up shop in Jacksonville.

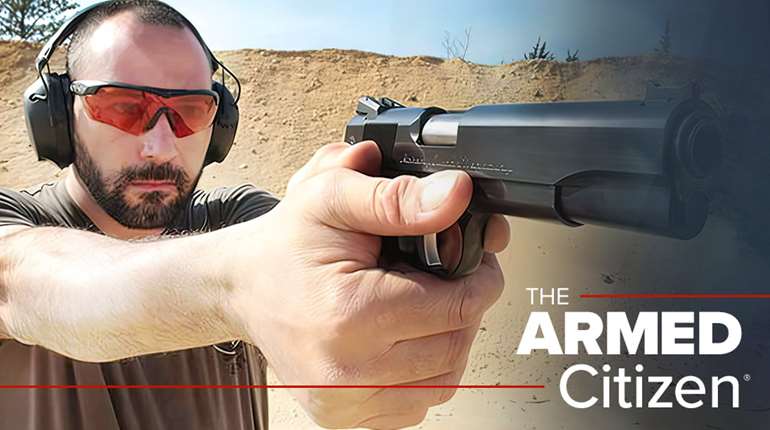

Chief Ballistician John Ervin aligned several gelatin blocks to capture the Elite Hunter Tipped bullets we would fire from a shooting bench 100 yds. away at an outdoor shooting range next to SIG’s grounds in Jacksonville. Ervin checked the temperature of the blocks and pronounced them ready to sacrifice their short existence for science.

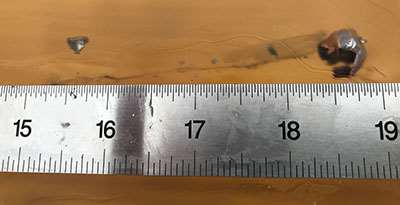

First was a Tipped 130-gr. bullet fired from a 6.5 mm Creedmoor. The bullet hit a block at a velocity of about 2600 f.p.s. The shot block showed the bullet had started to expand an inch into the gelatin and created a wide channel of disruption for 8", narrowing after that and stopping 16" deep into the block. The bullet had peeled back about three-quarters of its length, and the jacket and core remained joined with an expanded diameter of 0.513" and retained weight of 69 grs.

Next up were Tipped 165-gr. bullets fired from a .30-’06 Sprg. With an initial velocity of 2950 f.p.s., the bullets hit the blocks at a velocity of about 2770 f.p.s. One bullet plowed 19" into a block. Its expanded diameter was 0.615", and the bullet remained intact with a retained weight of 113.6 grs.

Creating a cartridge that shoots accurately through a variety of rifles is a formidable task. Consider the incalculable number of rifles and various action types chambered for the .243 Win. over the last 60-some years. Many SIG ballistic engineers are handloaders at home and have learned what propellants and primers tend to work with certain cartridges, and they apply that experience in SIG’s well-equipped loading room. “Load development is not rushed,” said B.J. Rogers, SIG’s ammunition manufacturing director. “It takes what it takes.”

Loads in the development stage are tested for pressure, primer and propellant compatibility, case neck tension on the bullet and velocity variations when fired in hot and cold temperatures. “We tend to use single-base powders when possible because they provide less velocity spread due to temperature changes than double-based powders,” Rogers said. A load that meets those standards is fired to check for consistency in up to five firearms. A cartridge’s accuracy is often the only attribute shooters see. SIG tends to load for accuracy. “But if accuracy arrives at the highest velocity we load for both,” Rogers said.

On the production line, cartridges are continually monitored for the correct overall length, primer seating depth and propellant weight. Samples are frequently fired in the 100-yd. shooting tunnel that stretches half the length of the SIG plant.

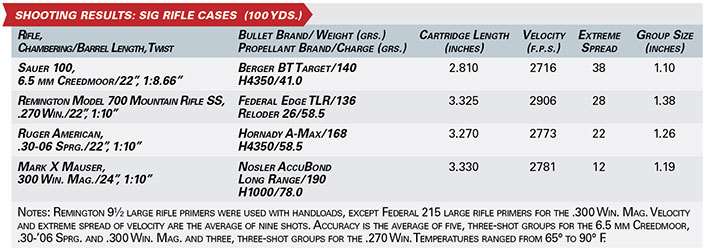

At home, I shot Elite Hunter Tipped loads in a Cooper Firearms Model 22 .243 Win., Sauer Model 100 Cherokee 6.5 mm Creedmoor and a Colt LE901 .308 Win.

The Cooper .243 shot groups as tight as 0.38" and as large as 1.48". One flier caused that outsized group, which may have been triggered by operator error. A 0.96" average for five groups is more than acceptable. Average velocity of 3076 f.p.s. of the .243’s 90-gr. Tipped bullet was only 39 f.p.s. slower than the advertised 3115 f.p.s.

Extreme spread of velocity of 76 f.p.s. over nine shots was rather high. However, it can be attributed to the first shot that clocked a relatively slow 3035 f.p.s. The Sauer 100 6.5 mm Creedmoor was close behind the Cooper rifle in accuracy, with a 1.08" average for five, three-shot groups shooting Tipped 130-gr. bullets. That average was a touch tighter than my carefully crafted handloads with SIG brass and Berger 140-gr. bullets.

I grease every moving part of my autoloading Colt .308 like it’s an old farm tractor, and the rifle keeps plowing along. The Colt shot 165-gr. Tipped bullets on either side of an inch at 100 yds., for a 1.10" average for five groups. Velocity was slow at 2662 f.p.s., but that’s expected from the Colt’s 16" barrel.

Cases

SIG started manufacturing handgun and rifle cartridge cases in 2018, initially for its ammunition. The next logical step was to offer brass to handloaders. The first rifle cases produced at the Jacksonville plant were .308 Win., followed by 6.5 mm Creedmoor. Available brass offerings now include .223 Rem., .22-250 Rem., .243 Win., .270 Win., .300 Blackout, .30-’06 Sprg. and .300 Win. Mag.

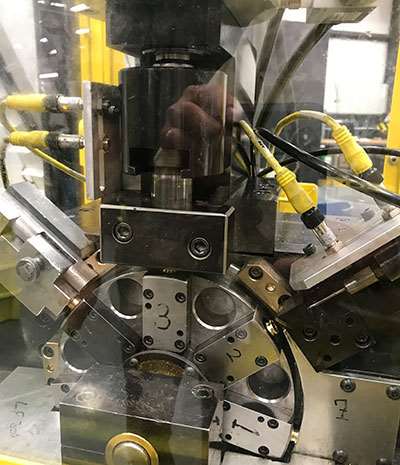

SIG operates two lines of brass production that were manufacturing .300 Blackout cases the morning Imhoff led a tour through the line of machines. Cases from each line are kept separate through every step of production and into packaging of 50 cases per bag.

Each “touching tool” that forms cases is attached to a strain gauge that relays the amount of pressure the tool applies. A gauge that detects a tool applying an undue amount of pressure stops the process and relays why it stopped. The problem is corrected before manufacturing resumes. Monitor screens attached to each forming tool display minimum and maximum allowable dimensions for the part of the case a tool constructs.

Monitors also show the dimension of the portion of a case each tool shapes. Those evaluations held steady between minimum and maximum. If a monitor detects an inconsistency, though, the line stops until the problem is solved. Annealing case necks is one of the last steps in producing rifle cases. SIG uses electricity for its uniform heat, compared to the pulsing flame from gas.

Case dimensions are given a final check through a machine at the end of the production line. Every so often the machine kicked a Blackout case into a reject bin. Imhoff picked up a reject that looked acceptable and studied it. “I’m guessing the case mouth might be a somewhat off-center,” he said. “Manufacturing cases on one line and measuring cases at each stage of construction minimizes variation.”

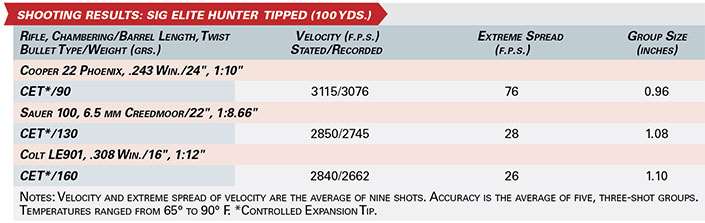

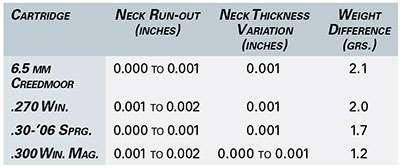

I weighed 20 each of SIG 6.5 mm Creedmoor, .270 Win., .30-’06 Sprg. and .300 Win. Mag. cases and used the fine-tooth comb of an RCBS Case Master Gauging Tool to gauge the cases for variation in neck thickness and run-out:

SIG Case Consistency Measurements

Cases for the four cartridges varied up to about 2.0 grs. However, the majority of the cases differed a few tenths of a grain. Of the 20 Creedmoor cases, 14 weighed from 156.9 to 157.7 grs. and 13 cases for .300 Win. Mag. weighed between 238.4 and 238.8 grs. Those are uniform weights.

Taking 15 additional cases for each cartridge, I loaded them with powder/bullet/primer combinations my records show had previously produced good accuracy and a low extreme spread of velocity. Rifles used to shoot the loads were pure hunting rifles and groups averaged not all that much over an inch for five, three-shot groups. Extreme spread of velocity for nine shots went from a high of 38 f.p.s. for the 6.5 mm Creedmoor to a low 12 f.p.s. for the .300 Win. Mag.

I measured the case head to datum point on the shoulder, or headspace, of all those cases before and after they were fired. Technically, the .300 Win. Mag. headspaces on the case belt, so manufacturers tend to set shoulders back far enough to prevent the neck from abutting the chamber before the cartridge is fully seated.

Because of that, firing can cause enough case stretch to thin the brass in front of the belt, and such weakening can cause the case to split around its circumference the next time it’s fired. This short-shoulder position is prevalent with about every brand of case wearing a belt. And while SIG’s .300 brass measured well within dimensional specifications, its case shoulders stretched 0.016" from their unfired to fired position. In contrast, new SIG .270 Win. cases lengthened just 0.005" on the shoulder and .308 Win. cases 0.004" on the shoulder from new to once-fired.

To give brass manufacturers their due, the problem may not be brass so much as rifle chambers. The Lyman 50th Edition Reloading Handbook states, “Generally, belted cases should be loaded no more than two or three times … . The short reloading life of belted cases is due to the overly long chamber dimensions that often occur in firearms so chambered and the high pressure used with the calibers.”

SIG elbowed its way into a crowded field when it started producing handgun and rifle ammunition, as well as specialized markets with its Elite Hunter Tipped rifle ammunition and cartridge cases for handloaders.

SIG’s attention to detail during every step of Elite Hunter and rifle brass production, though, has provided the company with the room to swing its arms of innovation at its expanded Jacksonville factory. That is certainly beneficial for SIG’s firearm businesses, and more importantly, for shooters everywhere.

For more information, go to sigsauer/products/ammunition.