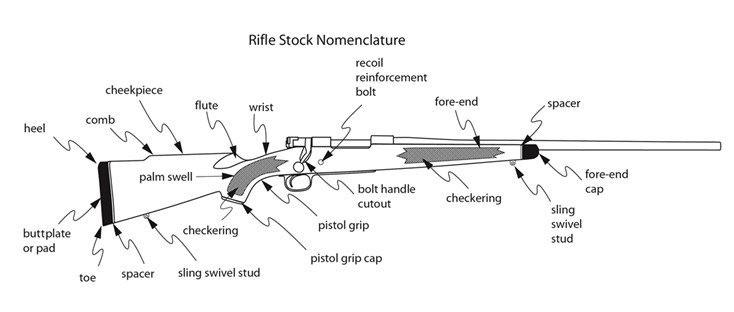

NRA Firearms Sourcebook image

Back to Basics: Rifle Stocks—Part 1 looked at the fundamentals of rifle stock design and the components of a stock. This second installment in the series looks into bedding platforms, materials and finishes.

As we have seen, the rifle stock has two primary purposes: to provide an interface between the rifle and the shooter and afford consistent support for the receiver and barrel. With traditional wood stocks this required the stockmaker to carve out a perfect mirror image of the bottom half of the receiver and barrel into the wood. It is an excruciatingly time-consuming task—I know; I’ve done it a few times. First the rough profile and dimensions need to be inleted into the stock blank. Go just a bit too much, and you will ruin the blank.

From there starts the time-consuming part. The stockmaker has to apply some form of marking agent—lampblack, soot, etc.—to the metalwork, then carefully lower it into the stock. He must put even pressure from one end to the other, then carefully remove the barreled action. Then he uses a variety of chisels and scrapers to remove only the wood that is marked with the agent. This ritual is repeated dozens of times until the entire profile of the underside of the barreled action marks the wood in the recesses completely and evenly. If too much wood is removed, the barreled action can move under recoil and split the stock. Too little, and stresses will be imparted to the stock that will at best destroy accuracy, or at worst split the stock. Many stockmakers included recoil bolts across the stock at the recoil lug area and occasionally the tang to provide additional support and prevent splitting in rifles of hard-recoiling calibers like the .375 H&H on up.

Boiled linseed oil was once the only acceptable finish for a wood stock. It has one real advantage—scratches can easily be repaired. But oil finishes are difficult to apply if you don’t know what you are doing. They are not nearly as durable as modern synthetics like polyurethane.

Thermosetic resins—commonly called epoxy—began seeing use in stockmaking during the mid-1950s. Some stockmakers used it at the recoil thrust points—basically the recoil lug and the tang—others tried bedding the entire barreled action from stem to stern. This required the stockmaker to “over inlet” the area to be epoxied to provide room for the compound. It also required them to provide escape vents for the extra compound. Some early stockmakers learned the hard way that everything—and I mean everything—attached to the barreled action must be completely coated with a release agent, lest the barreled action and wood would become one and the same, inseparable unless one component is destroyed. Fortunately for me, that never happened, but I know of a few rifle/stocks that are one and the same for eternity. Epoxy bedding became so easy that several manufacturers, like Winchester, used it to bed their rifle stocks in the mid-1990s.

Technology marches on, and stockmakers began to experiment with a variety of epoxy compounds in such ways as “pillar bedding” where support points were bedded on epoxy pillars in the stock and the rest of the bottom metal had clearance with the wood. About 20 years ago some stockmakers started making an aluminum chassis that mimicked the underside of the barreled action but had a simpler profile to be inleted into the stock. The chassis was machined on CNC machinery allowing it to be a virtual exact copy of the barreled action. It added negligible weight, was completely weatherproof and simplified the fitting process by saving a lot of time. Chassis bedding has become a widely accepted method of restraining a rifle within its stock, and like epoxy, has been adopted by a number of manufacturers.

Browning X-Bolt Pro

Today, most barrels are free-floated, meaning that nothing touches the barrel except where it joins the receiver. Steel and manufacturing techniques have evolved to the point that parts like barrels can be replicated with virtually absolute repeatability. This wasn’t always so. In days of yore, when a barrel blank was drilled, voids, pits or contaminate inclusions were not uncommon. Too, it was rare that a drill starting in the center of one end would exit the blank at the exact center of the other end. This required someone to set up the drilled blank on centers of the holes in a lathe and hand-turn the blank into an acceptable profile. All of these anomalies imparted stresses in the barrels that would need to be addressed later. It was once quite rare to find a barrel blank that was clean of stresses out of the lathe. Barrel makers had an overhead press with a wheel resembling an upside down ship’s wheel used for straightening stressed barrels—which, coincidentally, imparted its own stresses to the barrel. A pair of steel disks with small holes drilled in their centers were placed in each end of the blank. The barrel maker would then peer through the holes looking for a broken shadow line in the barrel. Wherever the break was, he would then set the press point at the break and give it a tweak.

These barrels required bedding at pressure points in order to dampen random vibrations that would occur during firing. This was more an art than a science and took years of practice to master. It is only when barrel making became a more precise process that the need to bed a barrel became obsolete. All barrels vibrate like a guitar string during firing, but modern barrels vibrate virtually identically from shot to shot, allowing the stockmaker to simply provide a clearance in the barrel channel of the stock to allow this phenomenon to occur freely.

In Part 1, we saw that rifle stocks were once made entirely of wood. Walnut was the predominant material because of its strength, durability and stability. However, stockmakers have used a variety of other woods such as maple, myrtle, beech, mesquite, even laminates, as well as many others. Most of the time these other woods were used for their aesthetic value. Occasionally, it was because the wood was readily available locally. This is why so many early American flintlock rifles were stocked with maple.

Remington experimented with plastic in the early 1960s with its Nylon 66 rifle and the XP-100 pistol.  Response at the time was ho-hum, but Eugene Stoner and Armalite used synthetics from the beginning for the AR-series of rifles. By the 1990s several manufacturers began offering stocks made from synthetic, man-made materials—everything from plain old plastic, to epoxy-coated foam and hand-laid, resin-impregnated carbon-fiber.

Response at the time was ho-hum, but Eugene Stoner and Armalite used synthetics from the beginning for the AR-series of rifles. By the 1990s several manufacturers began offering stocks made from synthetic, man-made materials—everything from plain old plastic, to epoxy-coated foam and hand-laid, resin-impregnated carbon-fiber.

Synthetic stocks have it all over any wood stock, save for aesthetics. They are lighter, stronger, impervious to any weather or moisture and more durable than wood. Also, unlike wood that can swell, shrink or warp, synthetics are 100-percent stable. They can make up some of the aesthetic issues in that they can be painted or finished to just about anything the mind can imagine. Once a mold has been made, a zillion identical stock blanks can be knocked out like Coke bottles for little more than the cost of the components and some negligible labor costs. Still, for some traditionalists like me, nothing can compare to the warmth and character of fine Circassian or English walnut. For us there must be a seamless melding of function and beauty in a rifle stock. We may be outdated, but we are resolute in our appreciation for a handmade, well-figured walnut stock.

Macmillan A5 Tactical Stock Sage International M1GALCS

Sage International M1GALCS

Metal has been introduced as a stock material during the past decade. Advances in lightweight, stronger-than-steel technology have allowed these alloys to be a viable material for rifle stocks. Metal has the advantage of being capable to be manufactured in small parts of any size and shape, making the fully adjustable stock a reality for the field. Heretofore such stocks were tool-room one-of-a-kinds that were used to determine final dimensions that were transferred usually into wood but also occasionally synthetics as well. It is now possible to make a rifle stock with enough articulation points that it allows the shooter to literally shoot around corners. These stocks have such a range of adjustability that an individual can quickly manipulate the dimensions of a stock to maximize its support capability from standing to kneeling to prone, with or without additional support. They are the leading edge of modern stock design and likely the future of rifle stocks.

It used to be that we chose the prettiest wood available for the rifle we wanted within the particular caliber. Unless you are very tall or short, requiring lengthening or shortening the stock was about all one could to custom fit a stock. That’s all changed today. Now a shooter can get a stock to accommodate his or her needs and modify it to really fit them. I may still swoon over fine walnut, but these adjustable stocks make shooting accurately and sometimes quickly much easier. Give those characteristics some serious consideration next time you are buying a rifle.