This article is excerpted from the downloadable anniversary book, Remington 1816-2016: 200 Years Of America’s Oldest Gunmaker.

To a degree—a large degree—the history of Remington is intricately intertwined with that of the republic. From the earliest days, Remington helped tame the frontier, provided security and promoted the shooting sports. Then when the necessity arose, the firearm powerhouse became a bastion of martial innovation and manufacturing.

The Beginnings

It is telling that after a number of years producing parts and barrels, Remington’s first complete gun was most probably a military carbine. The unorthodox U.S. Model 1840 Jenks is not one that immediately springs to mind when considering influential armament, but this innovative breechloader, issued primarily to the U.S. Navy, was clever and effective.

The Jenks was not designed by Remington, although the government was impressed enough with the company’s wherewithal to contract it for several thousand of these interesting contrivances in 1846. The gun’s most notable feature was its side-action “mule ear” lock. Two versions were manufactured—one that handled standard percussion caps and a second, in limited numbers, fitted with a Maynard tape-priming device.

At about the same time, Remington was included in a selection of makers to build the first U.S.-issue percussion rifle, the U.S. Model 1841 “Mississippi.” This handsome .54-caliber muzzleloader earned its nickname after being conspicuously carried by the red-shirted volunteers from Mississippi—led by future Confederate States President Jefferson Davis—during the Mexican War.

The 1841, also known as the “Yeager Rifle,” was largely manufactured at the Harpers Ferry Arsenal, but when demand exceeded supply, private firms were contracted. Remington turned out 10,000 between 1846 and 1854, and several variations of the popular frontier arm saw use on both sides during the Civil War.

Civil War

By the time the Rebels fired on Ft. Sumter in April 1861, Remington had established itself as a premier firearm manufacturer. Consequently, the federal government turned to the Ilion, N.Y., establishment to supply a variety of arms between 1862 and 1865. The company poured a goodly portion of its resources into fulfilling the military contracts—patriotic, but sound business when hostilities had eroded the sporting arms market.

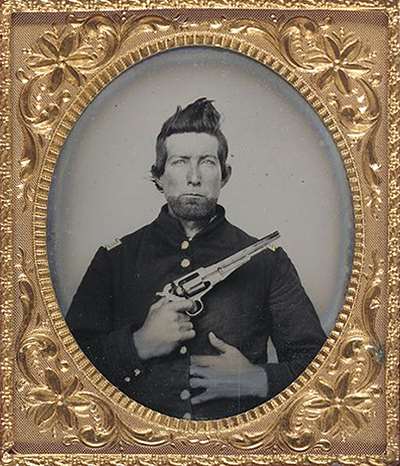

Like other firms, Remington took advantage of Colt’s expiring revolver patents, and as early as 1861 produced its first service-caliber six-shooters, the Beals .44 Army and .36 Navy models. Although the lockwork was primarily that of Colt, there were differences. The Remingtons boasted distinctive solid frames and a cylinder held in position by the closed loading lever.

Beals Armys were made in limited numbers (about 2,000), but the Navy variant was more positively received with 14,500 turned out and used by land and sea services. The Army was slightly larger, although the differences between the two handguns were negligible.

A year later, the Model 1861 Remington appeared, again in .44 and .36 calibers. The main differences between the ’61 and the Beals concerned the rammer, which had a full web and a space along the top to allow the cylinder arbor to be withdrawn without lowering the lever—a feature that proved so unpopular many were sent back to the factory to have the channel blocked with a screw.

In 1863, Remington introduced a pair of revolvers many shooters consider the finest percussion repeaters of their type, ever. The New Model Army and Navy differed from their predecessors in that they had unchanneled rammers and safety notches on the rear of the cylinders between the nipples to provide a resting place for the hammers when carried loaded. The New Model Army was especially valued, with the number purchased only surpassed by those of the Model 1860 Colt. The New Model Navy, while the match of the Army, never achieved the same popularity, possibly because of its lighter .36 caliber. As with the Beals and 1861s, civilian versions were also available.

Late in the war, the Ordnance Department put in an order with Remington to build 40,000 Model 1861 Rifle-Muskets, a Union Army workhorse fielded and produced in huge numbers by Springfield Armory. A variety of contractors also manufactured the firearm, although a large proportion of Remington’s ’61s were declared fourth-class arms—probably because they were delivered late in, or after, the conflict.

One of the more intriguing Civil War Remingtons was a high-grade short rifle variously termed “Harpers Ferry Pattern,” “Model 1863” or “Zouave,” the latter nickname the product of surplus arms dealer Francis Bannerman’s marketing savvy after the war, when he disingenuously connected it with exotic French-style Zouave units. This lovely arm, with its gleaming brass furniture, generous butt box, and abbreviated nipple bolster, looked much like a streamlined version of the 1841 “Mississippi.” Some 12,501 were manufactured between 1862 and 1865 but, mysteriously, none appear to have been issued. Today a large proportion of extant examples are in pristine condition, indicating the guns most likely remained in stores until they were sold as surplus.

Many fine rifles and handguns were devised during the war, but some of the most sophisticated appeared too late to see much, if any, service. Manufacturers struggled to maintain their firearm businesses afterward, but most were doomed, victims of military reduction and 1873’s financial depression.

Fortunately, Remington had an ace in the hole. In 1865 a clever breechloading carbine, which chambered a self-contained rimfire cartridge, was introduced and contracted for by the government. Known subsequently as the “Split Breech,” this efficient little arm, devised by Remington designers Leonard M. Geiger and Joseph Rider, was simple and reliable. Its action featured two basic main components—a hammer and a rotating breechblock. Apparently produced by Savage Arms under subcontract to Remington, the Split Breech was the last pattern of carbine delivered to the U.S. government during the Civil War. However, they arrived too late to see any action.

Fluctuating Fortunes

The Civil War proved profitable, with the Remington brothers receiving almost $3 million in payments from the government—all well and good, but what next? There was a glut of military arms in arsenals, although the majority were relatively obsolete by the late 1860s.

Remington recognized the opportunity, and strengthened the Split Breech’s action by making the block solid. The resulting “Rolling Block” was robust and simple to use. Unfortunately, it had one major drawback—muzzleloading rifles could not be converted readily or inexpensively, so ultimately, Ordnance Department authorities adopted the “Trapdoor” system devised by Springfield.

Still, the War Department experimented with and provisionally issued Rolling Blocks in the late 1870s. Some made by Remington, but others, such as the Model 1870 Navy and Model 1871 Army, were built at Springfield Armory.

Undaunted, Remington began promoting the Rolling Block to foreign governments that recognized the simplicity of the system—one easily mastered by unsophisticated soldiers. Those that did not have large stocks of arms to convert took a keen interest and the Rolling Block became the most widely dispersed military single-shot in the world, adopted by more than 40 countries. In the lean years following the Civil War, this arm, more than any other, was responsible for keeping Remington afloat.

Additionally, the Rolling Block was adaptable to a number of calibers and configurations, becoming popular in chamberings ranging from .22 to .50. Notably, Lt. Col. George A. Custer had a .50-70 Govt. No. 1 Sporting Rifle with him at the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

But time and technology moved on. Repeating arms became all the rage and Remington entered the field with a couple of bolt-action rifles—the Remington-Keene, which featured a tubular magazine and external hammer, and the box-magazine Remington-Lee, designed by James Paris Lee of Lee-Enfield fame.

While the Keene, made from 1880 to 1893, never elicited major governmental interest, the more forward-looking Lee was received politely by U.S. government officials, but only a smattering were ordered, and the majority of rifles and carbines—made from 1880 to 1907—were sold overseas.

The Great War

When World War I began in 1914, the United States was neutral, but still permitted the sale of arms and matériel to belligerents. Early on, Remington received contracts from the arms-strapped Russians for 1,500,000 copies of the Czarist Model 1891 Mosin-Nagant service rifle.

Great Britain, initially lacking enough Mark III Lee-Enfields, arranged for Remington and Winchester to build .303 British versions of an earlier experimental .276 English arm. The new rifle, termed the Pattern 1914, was different from the Lee-Enfield in that it had a Mauser-style action and internal, five-round box magazine. Several hundred thousand of these rifles were produced at the Ilion factory and Remington’s subsidiary Eddystone plant. By the time deliveries were received, though, the Brits had boosted their Mark III production to a point where the P’14 ended up largely relegated to reserve status.

Not to be outdone, France soon made arrangements for Remington to produce thousands of high-quality 8 mm Model 1907-15 Mannlicher-Berthiers rifles.

Unfortunately, the obstinacy of Czarist inspectors, coupled with the 1917 Russian Revolution, resulted in the cancellation of the Mosin-Nagant order, leaving Remington with 280,000 Model 1891s. The French, too, decided to abrogate their arrangement, and few of the Berthiers made it overseas. Fortunately, the U.S. government purchased most of these arms, using them largely for training purposes.

When the U.S. declared war on Germany in 1917, the American arsenal was woefully under-strength. Contracts began to fly, Remington being the recipient of a generous portion of the government’s largesse, centered primarily in the manufacturing of slightly altered, .30-’06 Sprg.-caliber versions of the British Pattern 1914. Officially termed the “United States Rifle Caliber .30 Model of 1917,” this arm, like the P’14, was made at Remington Ilion and Remington Eddystone plants, as well as by Winchester. Eventually, some 2,193,429 were turned out, making it the most widely used American rifle in World War I.

Uncle Sam was also somewhat low on handguns. As well as modifying Smith & Wesson and Colt revolvers to handle the .45 ACP service rounds, the government contracted with Remington-UMC and North American Arms in Canada, to fabricate Government Model 1911 auto pistols. Remington-UMC’s share of the total ran in the neighborhood of 21,500 guns, less than a tenth of the number cranked out by Colt up through 1918. Today good-condition Remington-UMC 1911s will bring a premium on the collector market.

Uncle Sam was also somewhat low on handguns. As well as modifying Smith & Wesson and Colt revolvers to handle the .45 ACP service rounds, the government contracted with Remington-UMC and North American Arms in Canada, to fabricate Government Model 1911 auto pistols. Remington-UMC’s share of the total ran in the neighborhood of 21,500 guns, less than a tenth of the number cranked out by Colt up through 1918. Today good-condition Remington-UMC 1911s will bring a premium on the collector market.

Remington’s other contributions to the Great War consisted of some 3,500 12-gauge Model 10 pump trench shotguns, a smattering of Model 11 autoloading 12-gauges, flare pistols and 12,000 Browning Model 1917 machine guns, probably making the firm’s output the most eclectic during the conflict.

World War II and Beyond

When America entered World War II, once again Remington was called upon. Probably the company’s highest profile product was a simplified version of the superb 1903 Springfield, a complicated arm that eventually morphed into the Model 1903A3 rifle. While retaining the basic lines of the ’03, the ’03A3 incorporated some stamped rather than milled parts, a Parkerized finish and a simplified rear sight. Despite its relative lack of elegance, the ’03A3 proved to be a superbly reliable and accurate arm, providing the basic platform for the U.S. military’s principal sniper rifle.

Model ’03A4 construction was undertaken solely by Remington beginning in 1943 and the last one emerged from the factory in early 1944. This arm differed from the standard ’A3 in that it featured a pistol-grip “C”-style stock and was sighted, most commonly, with a 21⁄2 power Weaver 330C scope.

While the ’03A4 enjoyed considerable use during the war, most of the ’03A3s were relegated to home-front/secondary issue or were supplied to allies. Still, by war’s end Remington had made 348,085 1903s and 707,629 ’03A3s.

It comes as no surprise that over the years several Remington shotguns have been enlisted into the military. High-profile World War II scatterguns included versions of the Model 11A autoloader and the Model 31 pump. Of course many of these found themselves being retreaded for the Korean War. When the Vietnam War arose, the superb Model 870 pump was called into service.

The success of the 1903A4 sniper rifle set the foundation for the adoption of several other Remington sniper rifles. The M40 (and variants), basically a Model 700 given a military makeover, was adopted by the Marine Corps in 1966 and saw considerable action in Vietnam. Also based on the Model 700/40-X was the series of M24s that first appeared in the late 1980s, chambered in 7.62 NATO.

Though the M24 is still with us, Remington is offering an even more sophisticated sniper rifle today, the MSR (called the M21 by the military). Introduced in 2009 and put into service four years later, the modular platform is available in 7.62 NATO, .300 Win. Mag., .338 Lapua Mag. and .338 Norma Mag.

So there you have it—from percussion muzzleloaders to space-age long-range precision rifles, Remington was there—and still is. It’s a proud call-to-arms, and one that would be difficult to equal.