“Remember the Alamo!”

Most Americans are familiar with the famous Texas rallying cry. But what is it we actually remember, and how do we remember it? What many believe to be fact may actually be just legend. Did William B. Travis really draw a line in the sand? Even historians disagree on some of the most well-known events. Did Davy Crockett really survive the battle and surrender? Much of our collective memory of the events at the Alamo comes from film and television. Did James Bowie really cut down the invaders with a seven-barreled Nock gun?  The Fall of the Alamo (1903) by Robert Jenkins Onderdonk (Wikipedia)

The Fall of the Alamo (1903) by Robert Jenkins Onderdonk (Wikipedia)

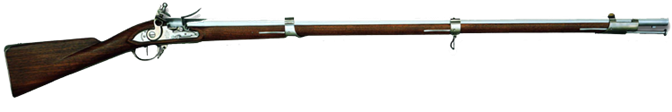

Putting aside the tales of heroics and the enormous personalities, we are at least able to arrive at some good ideas regarding the probable. Though there are very few remaining items that we can point to as direct evidence, we can determine what firearms were used by both sides in the 13-day siege in February 1836. Baker Rifle (NRAMuseum.org image)

Baker Rifle (NRAMuseum.org image)

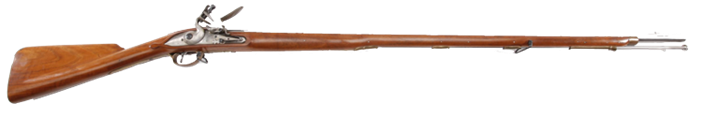

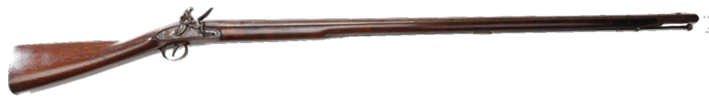

According to military supply records and artifacts found during excavations at the Alamo, the likely Mexican armaments are somewhat easy to identify. The average infantryman would have carried with him an India Pattern musket, a less expensive and inferior version of the British Brown Bess, weighing in at nearly 10 lbs. with a 39” barrel. Under optimal conditions and with proper training, the .75 caliber musket could have accurately hit a target at up to 100 yards and done serious damage to a military formation from as far as 300 yards. But because of the use of blackpowder, the barrels regularly fouled. Factor in the lack of sights, and these smoothbore muskets were wildly inaccurate. Mexican officers were often forced to wait until the enemy was practically on top them before giving the order to fire.

British Brown Bess (top) and Tower India Pattern Musket (NRAMuseum.org images)

Apart from the standard infantry, there was also a light infantry of highly trained Cazadores who were armed with a shorter and lighter version of the above musket, the India Pattern Sergeants Carbine. Fitted with bayonets, they were more suited to the close-quarter skirmishing that inevitably occurred when the same poor-quality powder began causing the familiar clogs in the barrels.

Some Cazadores, however, were armed slightly better, and again with British arms. The Baker rifle was a flintlock of .625 caliber with sights and brown rifled barrel a full foot shorter than the muskets. It had a realistic accuracy out to 100 yards with a much-improved maximum range of up to 250. The British, however, were reporting incredible distances of up to 600 yards with Baker rifles improved upon in later designs. It was designed to use paper cartridges for quicker reloading but it still fired only at half the rate of the India Pattern Sergeants Carbine.

Mexican cavalrymen were known to carry a short-barreled large-caliber carbine in their saddle holsters, the 1812 Tower flintlock, and very likely a matching pistol.

U.S. J. Bishop Model 1812 Flintlock Militia Musket (NRAMuseum.org image)

Aside from the personal sidearms of officers, it is assumed that very few firearms other than the ones listed above were to be found in the Mexican camp. The necessity of transferable parts and ammunition among the army made for little variety.

Mexican artillery was described specifically by Travis in a letter a few days before the fall. “From the 25th to the present date, the enemy have kept up a bombardment from two howitzers (one a five and a half inch, and the other an eight inch) and a heavy cannonade from two long nine-pounders, mounted on a battery on the opposite side of the river, at a distance of four hundred yards from our wall.” The effectiveness of the cannonade was nearly nullified by the reinforced barricades concocted by Travis, as well as his masterful placement of the Alamo’s own cannons: “At least two hundred shells have fallen inside our works without having injured a single man.”

The cannons within the Alamo are also somewhat uncomplicated to assess thanks to a collection of sources, including Santa Anna’s own post-battle report. In all, when the Mexican forces burst through the walls of the Alamo, they found 21 cannons of varying sizes and shapes, three of which had never even been fired. The defenses included the 18-pounder that Travis used to respond to Santa Anna’s call for surrender, a 16-pounder, a merchant ship’s iron 12-pound gunnade, a 9" pedrero, two iron 8-pounders, six 6-pounders, four 4-pounders, and two 3-pounders. By the end of the siege, most of these had become scatterguns, a dearth of shot and shell led to the operators filling the tubes with horseshoes and chains.

Turning to the makeshift army of the Texians themselves, we find that the defenders of the Alamo were a varied lot. Besides the Texas colonists, the men who answered Travis' call hailed from more than 20 other states and territories, from Illinois to Vermont. Davy Crocket brought his volunteers down from Tennessee. Jim Bowie sprang from Louisiana via Kentucky. William Travis from Alabama via South Carolina. Dozens of others found their way into the mission fort from not only Mexico, but also England, Ireland, Scotland, Germany and even Denmark. Their ages were just as ranging. William King was a mere 10 years old when he manned a cannon against wave after wave of Santa Anna’s infantry. Gordon Jennings, 56.

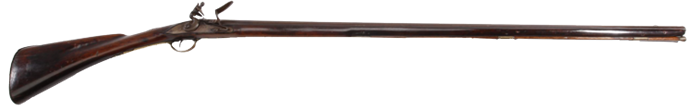

Unlike the regular army of Mexico, such a disparate group that made up this “Army of the People” no doubt brought with them an equally varying array of personal arms. Precisely what small arms were used, though, remains elusive. We do know that the inventory made after the battle listed 816 muskets, rifles and pistols, and 14,600 cartridges being loaded onto a supply train back to Mexico. And we perhaps also know that the official count of firearms on the train should actually have been at least one more. One of those rifles, a Pennsylvania longrifle, was plucked from the ashes by a Mexican citizen of San Antonio who decided to keep it as a memento of the slaughter. The rifle was later given to Frank Johnson, a Texian that had left the Alamo before the siege began. The rifle then changed ownership several more times over the decades until 1947 when it finally ended up back where it belonged, in the Alamo museum.

This specific Pennsylvania rifle, known by many names but most commonly as a Kentucky longrifle, is the only firearm in the Alamo museum today whose provenance can be traced directly back to the battle. However, it is a certainty that it is not the only longrifle to have been fired during the siege.

Kentucky Longrifle (NRAMuseum.org image)

The longrifle was a specifically American invention, developed in the 1700s for hunting the western wilderness of the early colonies. It could fire accurately well in excess of 200 yards thanks to the revolutionary spiral grooving in the bore developed and perfected by Germanic immigrants to Pennsylvania. Suited to its owner, it could be 4 to 6 feet long and was available in calibers from .25 to .62. They remained the most effective and popular rifles for decades, crossing all class barriers. It is undeniable that a great number of these rifles, as well as matching calibered flintlock pistols, found their way south to the Texas colonies in great numbers. Sturdier iterations made in the southern and western states for bigger game, such as the Mountain rifle and the Trade rifle, were likely just as prevalent.

In the five months prior to the siege of the Alamo, the Texians had been steadily battling the Mexican army back towards the Rio Grande. By the time the last Mexicans were pushed across the river, the Texians had collected a vast supply of surrendered Mexican arms. Desperate for any and all spare weapons in their fight for their freedom, the same Indian Pattern muskets and Baker rifles described above would soon be turned on their former owners. U.S. Henry Deringer Model 1814 Common Rifle (NRAMuseum.org image)

U.S. Henry Deringer Model 1814 Common Rifle (NRAMuseum.org image)

Standing out from an otherwise mostly rag-tag group of men at the Alamo were the New Orleans Greys, named after the matching grey fatigues they sported. The 23 volunteers were armed as a regular company of soldiers would be and when they set out from New Orleans, the majority of the men whose lives would end at the Alamo were equipped with the Deringer M1814. Known as the common rifle, these were .54 caliber flintlock muzzleloaders with 36” rifled barrels capable of being loaded with paper cartridges. Their angled stock was intentionally reminiscent of the graceful Kentucky long rifle mentioned above. Those Greys unfortunate enough to have not been issued a common rifle instead carried a U.S. Pattern musket, Springfield Model 1795, taken from the French Charleville design. The .69 caliber flintlocks were essentially only short-range arms good for firing into formations, their accuracy quickly reducing as the target surpassed 50 yards. 1795 Springfield Flintlock Infantry Musket (imfdb.org image)

1795 Springfield Flintlock Infantry Musket (imfdb.org image)

Like the Greys, a preponderance of guns brought in to service during the Texas Revolution came in from along the Mississippi River. The former French colonial Louisiana stretched from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico, and firearms there were as essential as food and water for the hunters, traders and trappers that populated the land. The most common long guns were by far the Fusil de traite, the Fusil fin, and Fusil de chasse, .62, .65 and .69 calibers respectively. Tens of thousands of these flintlocks had been flooding the territories along with half a dozen variations of the Charleville musket for a century before the French departed. These were no doubt well-represented at the Alamo.

French Flintlock Fusil (NRAMuseum.org image)

Any estimation of the Alamo’s defensive capabilities would be incomplete without mentioning fowlers, scatterguns and blunderbusses. These short-barreled shotgun-style smoothbores have always come in a wide variety of flavors and have always been found Texas. Whether flintlock or percussion these escopetas were easy to load and easy to fire. Col. Travis’ arm of choice was a double-barreled shotgun, and witnesses describe him emptying both barrels into the advancing troops seconds before he was lost to the cause. One can imagine that during the final bloody moments of close range combat at the Alamo, the shotgun was a primary actor all around.

U.S. Harpers Ferry 1805 First Model Flintlock Pistol (NRAMuseum.org image)

Although no archeological evidence has been found, no doubt the Texians were armed with typical flintlock pistols of the era, with a typical example being the Harpers Ferry Model 1805.

Along with all of the rifles, muskets and pistols already listed, one’s imagination is the only limit to the possible firearms that saw use at the Alamo. Whatever the cannons and fires hadn’t destroyed, anything in the least way valuable found among the bones and ashes was no doubt secreted away by soldiers and scavengers before it could be added to the official reports. It’s highly unlikely that any specific firearms will ever appear again with a direct link to the battle. One will always wonder though, when one comes across a long rifle at an estate sale or when one sees an old rusted musket barrel for sale in a San Antonio antique shop, if perhaps it had been witness to the siege that sparked the cry, “Remember the Alamo!”