image: Leupold Optics Academy

The term “trajectory” is often bantered about in discussing ballistics, but few truly understand it. In its most basic and broadest sense, trajectory is the path an object takes as it moves through space, as a function of time. A trajectory can be circular, as in the path most moons describe about their planet; it can be elliptical, as most planets describe about the sun; and, theoretically, a trajectory can be linear as an object traveling through space without any gravitational influences.

Here on Earth, and as it relates to projectiles launched from a firearm, a trajectory is almost always a portion of a parabola—a two-dimensional U-shape path with a mirror symmetrical curve. That’s not wholly true, as bullet trajectories can be influenced by wind, bullet spin (often referred to as spin drift); even the turning of the Earth (Coriolis effect).

Image: NRA Firearms Source Book

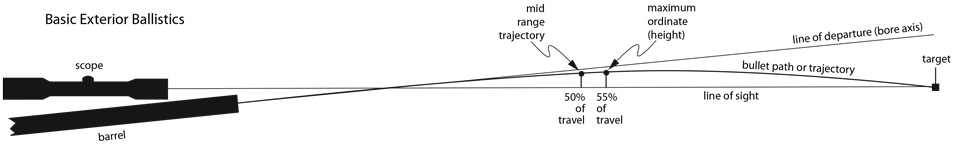

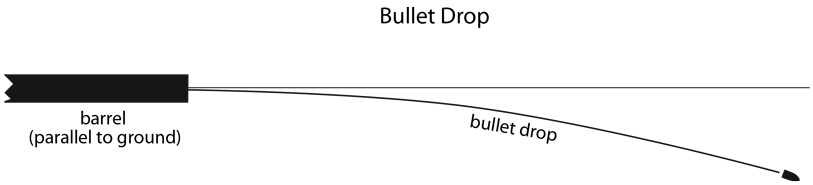

A foundational axiom we must understand before going any deeper is: If you had a firearm with its barrel perfectly perpendicular to the center of the Earth at a given distance from the Earth, and you were able to release a bullet separate from the firearm but at the instant and exact same height from the ground the first bullet cleared the muzzle, both bullets would hit the ground at the very same instant—provided the ground was flat. The distance from the firearm that the bullet was launched from is a function of the velocity of the bullet and time. It is important to understand that a bullet begins falling away from the centerline of the bore the instant it clears the muzzle. This is true whether the centerline of the bore is perpendicular to the Earth or it is elevated slightly—what we call “angle of departure.” It is also vital that a shooter understand the difference between line of sight—a straight line—and the trajectory of a bullet, which is parabolic.

If the angle of departure is 0 degrees—i.e. perpendicular to the earth—the shooter would always have to hold over his target in order to get a hit. However, if the shooter can elevate his muzzle slightly, it is possible to hit at two different distances. If the firearm has adjustable or telescopic sights, the shooter can sight the firearm in, or set it so that he can make hits at a range of distances repeatedly.

Hunters can take advantage of this phenomenon of having the same point of impact at two distances. By adjusting his sights correctly, he can virtually guarantee effective hits over a pretty fair distance. We call this Maximum Point Blank Range (MPBR)—whereby he can place his shot within 5 - 6" of his point of aim. Visualize a volleyball in the center of the chest of a deer or elk. Any shot that penetrates that sphere is going to result in a dead animal. To achieve this sight setting, most hunters utilizing the MPBR method usually set their sights so that at 100 yards their bullets will impact 2 1/2 to 3" high. Depending on the cartridge and bullet weight, this hunter does not need to concern himself with the exact range until his game animal is more than 250 to 300 yards away.

Some varmint shooters employ this method but with a narrower range, say within plus-or-minus 2" of point of aim. A lot of modern-day varminters and precision shooters require even more precise aiming in order to hit their objective. As the distance from the target increases, the need for more precision becomes necessary.

Image: NRA Firearms Sourcebook

Although there ammo companies now manufacturing better loads suited for long-range shooting, Long-range-precision shooters—which includes varmint shooters—almost universally handload their ammunition. Precision is the keyword here, and only by handloading and knowing the velocity of their load and the precise distance of their target can they utilize the components of their rather specialized equipment to its maximum effectiveness. Such precision relies on good dope—the ballistic factors of a given load—as well as the shooter maintaining proper shooting discipline.

A term that you will likely hear when a bunch of shooters get together for a discussion is “mid-range trajectory.” It is sort of a misnomer, but it means that point in the trajectory of the bullet where it is at its highest point relative to the line of sight. Let me give you a somewhat obtuse example to illustrate. A few years ago I was at the NRA Whittington Center with a group known as The Shootists. It’s a gathering of dedicated shooters, and it’s a great place to go and learn little-known tidbits about shooting and guns.

Several of us retired to the silhouette range where, well beyond the normal silhouettes, at 1,123 yards, is a life-size steel target of an American bison. In what would be the chest area of the bison there is a 24" diameter by 2" center target on a vertical axis. I was shooting my Sharps replica chambered in .45-90-2 1/2. Muzzle velocity for my 520-gr. Postell bullet is 1,150 fps. In order to hit the bison, I have to elevate the rear sight to within a quarter-inch of topping out. With the sight that high, you don’t cheek the comb, you chin it. If the wind wasn’t blowing, I eventually—after about 10 shots—got to the point where I could hit the 2" center on demand, from the bench. Back home, I ran the particulars through my Oheler Ballistic Explorer software and found that my bullets had to rise and fall 66 feet from muzzle to target. Ergo, the midrange trajectory for that shot is 66 feet.

Of course, with modern cartridges the mid-range trajectory for a shot like that would be much less. Mid-range trajectory is usually important to hunters who are searching for their perfect sight setting for MPBR. After all, you don’t want to shoot over the deer with a center hold.

All of this except the bison target example assumes the bullet is flying in a vacuum. Air resistance, wind and other factors contribute to the actual flight of a bullet. However, what you have read here will be critical to understanding the other factors as they relate to accurate predictions of a bullet’s flight.