The saga of the Rigby Big Game rifle has taken remarkable twists since Aug. 29, 1912, the day Col. Sir Aubrey Woolls Sampson, hero of the Anglo-Boer wars, took delivery of the first of the famed dangerous-game guns. The big .416 Rigby, built on the Mauser Magnum action, was slow to catch on. Only 189 are believed to have been produced through 1940, at which point World War II halted supply of the key component from Germany. When post-war manufacture resumed, relatively few could be produced, so the London gunmaker attempted to modify surplus 98Ks or utilized derivative actions such as the French-made Brevex or the BRNO from Czechoslovakia when they could be obtained.

Help came unexpectedly when American writer Robert Ruark made the Rigby a virtual character in his popular works, Horn of the Hunter (1953) and Something of Value (1955), in admiration of the way professional hunter Harry Selby wielded his Rigby during safaris in East Africa. Around campfires worldwide, that spotlight elevated the .416 over other magazine-rifle calibers, accruing acclaim that would pay dividends in future demand.

Rigby remained a London fixture until the 1990s, but then a series of ownership changes, along with a trans-Atlantic legal fight, resulted in competing production in both the U.S. and in England. The turmoil came to an abrupt halt in 2013 with the acquisition of Rigby, and all of its marques and records, by the Swiss/German L&O Group, whose portfolio includes SIG Sauer, Blaser and Mauser. In effect, the clock was turned back a century to when Rigby, as Mauser’s exclusive London agent, persuaded the Germans to enlarge their action so that it could compete with big-bore double rifles.

Rigby remained a London fixture until the 1990s, but then a series of ownership changes, along with a trans-Atlantic legal fight, resulted in competing production in both the U.S. and in England. The turmoil came to an abrupt halt in 2013 with the acquisition of Rigby, and all of its marques and records, by the Swiss/German L&O Group, whose portfolio includes SIG Sauer, Blaser and Mauser. In effect, the clock was turned back a century to when Rigby, as Mauser’s exclusive London agent, persuaded the Germans to enlarge their action so that it could compete with big-bore double rifles.

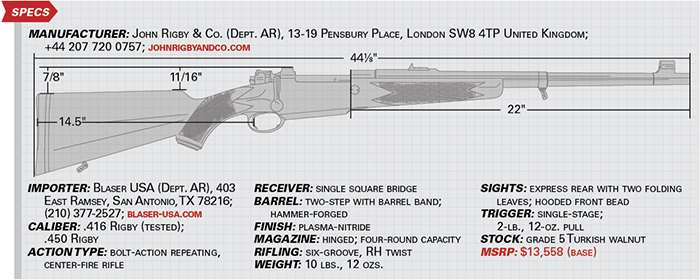

Since the 2013 restoration, orders for the Big Game have exceeded the entire pre-World War II production. Two models are offered, both single- and double-square-bridge variants. The former—including the sample we received—is made in traditional express rifle mode, lacking provision for scope mount and featuring a folding-leaf rear sight and over-the-top safety. The double-bridge variant is intended for use with optics and accordingly sports a lateral swing safety.

Today’s barreled actions from Mauser differ from the originals only in minor respects. Present is the familiar bolt fitted with full-length claw extractor and twin opposing locking lugs, the left one split to straddle a fixed, blade-type ejector. A functional third lug is found on the bolt stem, which locks into a cut in the receiver tang. Further strength comes from internal structure. Both action screws protrude through steel pillars that bear directly on the flat-bottomed receiver, and the integral recoil lug extending beneath the receiver ring engages a rectangular, case-hardened, steel bolster contained within the stock. This rigid, steel-on-steel foundation all but ensures consistent bedding pressure, thus minimizing possible effects on accuracy and feeding caused by overtorqued screws and wood shrinkage or swelling.

Today’s barrels are hammer-forged, and at 22" are 2" shorter than original issue. They come in a two-step contour, narrowing from 0.952" at the barrel band sling swivel mount to 0.785" at the muzzle. The rear sight teams a fixed 65-yd. blade with folding 150- and 250-yd. leaves, mounted on a quarter rib fronting the receiver bridge. Affixed to an over-sleeve extending back from the muzzle, the hooded front sight ramp is fitted with an interchangeable brass bead.

The rifle’s ovular trigger guard attaches to a hinged floorplate covering a dropped-box magazine that bellys about a quarter-inch below the stock, thus creating sufficient capacity for four of the beefy .416 cartridges.

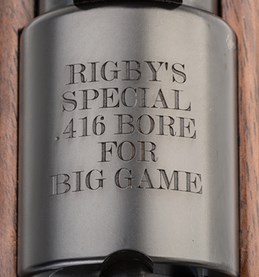

Stampings proudly echo the gun’s heritage. The front bridge bears the same inscription it wore in 1912: “RIGBY’S SPECIAL .416 BORE FOR BIG GAME”; while the left side of the receiver states: “MAUSER M98 MAGNUM Made in Germany.”

Our test rifle’s notably stout stock was streaked with straight-lined, dark figure, mindful of the tendency of heavy-kicking guns to crack along pronounced burl. It was very attractive, though not so showy as high-grade stocks often adorning less powerful rifles. The wide-radius pistol grip and fore-end were bracketed with hand-cut, 22-line-per-inch, bordered checkering, both areas providing ample handholds that complement the recoil mitigation afforded by the stock’s high, rounded comb and stiff, red rubber buttpad. The satin finish was near perfect, but more attention could have been devoted to fill on such a costly gun. Wood-to-metal fit was superb. An added feature is a small compartment accessed through the color-casehardened grip cap.

Shooting the Big Game, which delivers 58 ft.-lbs. of recoil energy (three times greater than a typical .30-’06 Sprg.), was thrilling and jarring, but tolerable thanks to the smart stock design and a weight of 10 lbs., 12 ozs.

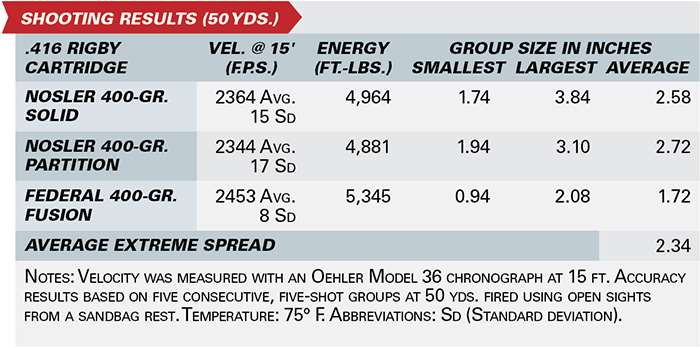

We test-fired the rifle from the bench utilizing a Caldwell Lead Sled 2, as well as from sticks and offhand. Groups at 50 yds. were disappointing, at least in part because of the difficulty in shooting such a hard-recoiling, open-sighted gun from a benchrest. The groups tended to widen with the last couple shots, and often we observed three-shot clusters of about an inch. Such rifles are predominantly fired from the standing position and we noted accordingly that first-shot accuracy from sticks was comparable to our bench results. When cycling through the magazine freehand at distances ranging from 15 to 40 yds., we were able to hit milk jugs without fail, and there were no misfires or failures to feed or eject spent cases. Bench accuracy results notwithstanding, this rifle is highly capable of the close-range work for which it is intended.

The over-the-top safety requires attention. In the “3-o’clock” position it securely locks both firing pin and the closed bolt against unintended operation. With the “flag” up, the firing pin remains locked but the bolt can be retracted for clearing the chamber safely. This position also blocks the sight line, thus serving as a reminder that the safety is on. At “9-o’clock” the gun is ready to fire.

The Rigby Big Game is a highly specialized and expensive tool for meeting the needs, tastes and sensibilities of a unique subset of firearm owners. Beyond that, it is a living artifact of an era that exerted profound influence over shooting culture and the freedom inherent to firearm ownership and hunting. That it has been resurrected in a near-mirror image of the original production can only be seen as a positive, “canary in the coal mine” indicator of how that freedom endures.