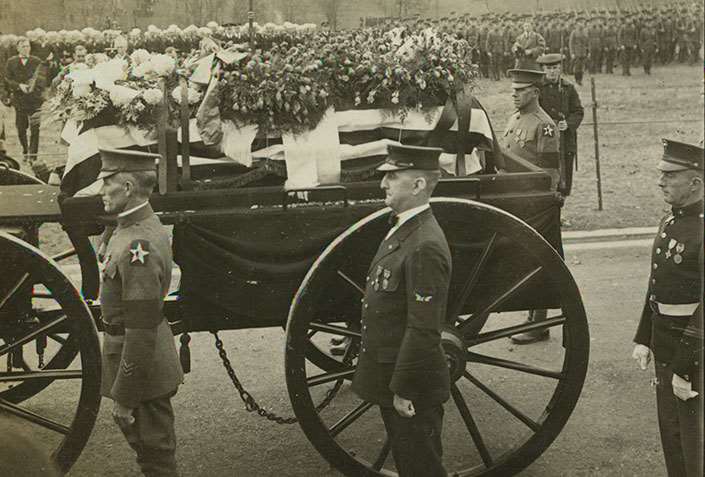

Marines carried their newly issued M1918 Browning Automatic Rifles during their assault across the Meuse River on the last night of the war, Nov. 10-11, 1918. The eagle, globe and anchor insignia that some Marines wore on their helmets denotes them as “Devil Dogs”— a translation of “Teufelhunden” (or, more correctly, “Teufelshunde”), the sobriquet bestowed on them by their German adversaries, according to Marine Corps lore.

As the figures in field-gray uniforms emerged from the woods, formed up in ranks in the field of ripening wheat and began their assault across the field, raspy-throated sergeants, nearly a half-mile away, barked out sight adjustment details to the prone riflemen in forest-green and olive-drab uniforms spread out in front of them on the small ridge. The Marines of the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, lying in the grass at Les Mares farm, carefully adjusted the sliding apertures on their rear sights and dialed in the windage estimations on their Model of 1903 Springfield rifles, while laying out five-round stripper clips of .30-’06 Sprg. ammunition beside them for easy access. When the long line of Germans came to a point hundreds of yards away, the Marines opened up on them and kept on firing, until the repeated German assaults were broken, and the enemy retreated. The attacking Germans never made it to within 200 yds. of the Marines’ position, and this was the closest point that the German army ever came to Paris during World War I.

As Col. John W. Thomason, one of the most famous chroniclers of the Marine Corps, described the action: “Already, around Hautevesnes, there had been a brush with advancing Germans, and the Germans were given a new experience: rifle-fire that begins to kill at 800 yards; they found it very interesting.”

The next day, June 6, 1918, long lines of Marines charged into the fire from spitting muzzles of German Maxim machine guns, as the Battle of Belleau Wood began. More Marines lost their lives on that day than had died in combat during the preceding 120 years of the Marine Corps’ existence. The battle raged for weeks, and many more Marines died, until Belleau Wood was finally declared secure—but this was only the first of a series of five major battles that Marines fought on the Western Front in France during the following six months. The Marines fought these battles mostly with the same small arms and crew-served arms that were also being employed by the U.S. Army, but with a few exceptions.

Foremost in the Marine Corps’ arsenal was the .30-’06-chambered Model of 1903 Springfield rifle. Although Marines would not again have the opportunity to engage the enemy at such ranges as they had at Les Mares farm, they used their Springfield rifles to great effect until the Armistice on Nov. 11, 1918. Marines had begun trading in their .30 Army (.30-40) Krag-Jorgensens for this new rifle as early as 1908, which coincided with the year that saw the Corps’ interest increase in competitive marksmanship. Within a short period of time, Marines were winning interservice matches with the rifle, and they began to form almost a cult reverence for the ’03 Springfield, as it began to be called. Based on a bolt-action Mauser design, the gun was shorter than the Krag, and, like the British Short, Magazine Lee-Enfield (SMLE), it was one of the world’s first “universal-issue” shoulder arms issued to infantry, cavalry and support troops, rather than being provided a carbine for mounted troopers and artillerymen, and a long rifle for infantry.

The ’03 rifle fired five rounds of .30 U.S. ball ammunition from its internal box magazine. It could be sighted for up to 2,700 yds., with a sliding, graduated rear sight that had both an open notch and a round aperture, as well as a flat “battle sight” set at 547 yds. The rear sight also had a dial that was set for increments of 4.4" for every 100 yds. of distance, in order to compensate laterally for windage. The combination of this rear sight and the thin-bladed front sight was a competitive shooter’s dream. The .30-’06 cartridge, now with a 150-gr. pointed (spitzer) jacketed bullet, had replaced the earlier .30-’03 version, with its round-nosed 220-gr. bullet, and it now generated a velocity of 2,800 feet per second (f.p.s.).

While many U.S. Army units (mainly “draftee divisions”) were issued the stopgap .30-cal. Model of 1917 U.S. “Enfield” rifle, the Marine Corps, aside from using a few Enfield rifles for training at the Marine Corps’ new base at Quantico, Va., and at various posts in the Caribbean, almost exclusively used Springfield rifles. Common knowledge since World War I among Marines has been that the 4th Brigade carried only Springfields, but in recent years, documentary evidence has been found to the contrary. In a response to an inquiry after the war, the commanding officer of the 5th Marines’ Supply Company, and later brigade quartermaster, Bennett Puryear, Jr., asserted that Marines of both the 5th and 6th Regiments were issued both Springfields and Enfields. However, the lack of Enfields in any extant photographs of Marines in Europe, or any mention of them in any known memoirs, correspondence or accounts leads one to believe that any issue of Enfields in France was very limited, and most probably only on an emergency replacement basis. Some may have been brought over by the last group of replacements to arrive in France. As such, an Enfield in the 4th Marine Brigade would have been somewhat of a rarity.

Corporal John H. Pruitt is among the many Marines who received decorations for valor while using his M1903 Springfield rifle (serial number 171397). Pruitt’s citation for the Medal of Honor reads: “For extraordinary gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty while serving with the 78th Company, 6th Regiment, 2d Division, in action with the enemy at Blanc Mont Ridge, France, October 3, 1918. Cpl. Pruitt single-handed attacked 2 machine guns, capturing them and killing 2 of the enemy. He then captured 40 prisoners in a dugout nearby. This gallant soldier was killed soon afterward by shellfire while he was sniping at the enemy.”

Slovakian-born Sgt. Matej Kocak, another Marine who was awarded the Medal of Honor, rushed a German machine gun nest with his rifle (serial number 576472) and fixed bayonet during the July 1918 Battle of Soissons, drove off the crew and then led a group of French colonial Senegalese troops in a successful attack on another machine gun nest.

At the same battle, Sgt. Louis Cukela, another recent immigrant—this one from Croatia—also used a Springfield rifle (serial number 381782), with its M1905 bayonet attached, to capture several German machine gun nests. In addition to the M1905 bayonet, with its 16" blade, Marines also used the French Viviens-Bessière (or “VB”) rifle grenades. Originally designed for the 8x50 mm R Model 1886 Lebel rifle, but later adapted to U.S. Springfields and M1917 Enfields, the cup-shaped attachment at the muzzle of the rifle was used to launch cylindrical grenades, with the bullet of a service round going through a small hole in the grenade and igniting the fuse.

While some later ’03s can be attributed to the Marine Corps by certain characteristics, such as “Hatcher holes,” electro-engraved numbers and barrel markings, the Springfield rifles that were issued to Marines during World War I do not bear any identifying markings, as such. Aside from research conducted and published by the late Franklin B. Mallory many years ago, there has not been a serious attempt to analyze official USMC Quartermaster records of the period, and to then compile a listing of known serial numbers. There is no correlation between known serial numbers and dates of issue—for example, Louis Cukela was issued Springfield M1903 rifles with serial numbers 576507 and 215359 in prior enlistments, before being issued rifle number 381782, at least a year before he shipped off for France. It is known that the Marine Corps received pistols that are identified by serial number blocks in the pre-World War I period, but, again, more research needs to be done, in order to identify all of the World War I-era M1911 pistols that may have actual Marine Corps provenance.

While enlisted Marines serving as infantry and as supporting troops carried Springfield rifles, Marine officers, senior non-commissioned officers (NCOs) and gunners of crew-served weapons carried the venerable M1911 Colt semi-automatic pistol—a firearm that hardly needs any introduction here. Again, many U.S. Army officers and men carried yet another stopgap firearm—the Colt or Smith & Wesson M1917 revolver, also in .45 ACP—but, with the exception of a military police company in Paris, Marines were issued the semi-automatic pistols exclusively. Abandoning their .45 Colt M1909 Colt revolvers in 1912, the Corps eagerly adopted one of John M. Browning’s most enduring designs—and soon put it to good use. By the time of World War I, many Marines were carrying their pistols in M1916 leather holsters, although some pre-war officers still retained their M1912 mounted holsters (with some embossed with “USMC” on the flap), while some other senior NCOs wore M1912 dismounted holsters.

As early as 1915, Marines were using M1911 Colt pistols in actions that resulted in awards of the Medal of Honor (“Guns of the Banana Wars, Part Two,” February 2013, p. 42), and numerous Marines were cited for gallantry in actions that involved Colt pistols during World War I. Perhaps the most famous Marine of World War I, then 1st/Sgt. Dan Daly, used his pistol (serial number 151589) in the action for which he was awarded both a Navy Cross and an Army Distinguished Service Cross near Belleau Wood. After his Springfield rifle (serial number 223688) was blown from his hands near Belleau Wood (and for which he grudgingly had to repay the government!), Pvt. John J. Kelly was issued a pistol to replace it, since after recuperating from his wounds Kelly was now assigned as a company runner. Private Kelly used this pistol at Blanc Mont to kill a German machine gunner and capture the gun and its crew—a feat for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor. During an earlier fight at Saint-Mihiel, Kelly also manned Chauchat automatic rifles on at least two occasions, when their gunners were killed or wounded.

Automatic arms proved to be an interesting story in the Marine Corps. In the pre-war period, Marines had manned M1909 Benét-Mercié light “Machine Rifles” and M1895 Colt-Browning heavy “Potato Digger” machine guns (“Guns of the Banana Wars, Part One,” December 2012, p. 54.) However, both of these machine guns left much to be desired. The U.S. Army opted to replace its fragile and unreliable Benét-Mercié machine rifles—and its obsolete M1904 Colt-Maxim heavy machine guns—with the British-designed Vickers machine gun (actually, an improved Maxim design) in 1915. However, the Vickers was a heavy, tripod-mounted and water-cooled gun.

In 1916, (at the urging of Edward B. Cole, the “father” of Marine Corps machine guns) the U.S. Navy decided to adopt the Lewis light machine gun, which was then being manufactured for the British by the Savage Arms Co. in Utica, N.Y. An American invention, but produced and used overseas because of a long-standing feud between its inventor, Col. Isaac N. Lewis, and Gen. William Crozier, the U.S. Army’s Chief of Ordnance, the new American version of the bipod-mounted, shoulder-fired machine gun was, like the ’03 Springfield rifle, chambered in .30-’06 Sprg. Firing 47 rounds out of its distinctive top-mounted drum magazine, the air-cooled Lewis gun quickly became a favorite of Marines training at Quantico, and handcarts were developed (again by Cole) to carry the guns into battle.

However, after landing in France, the Marines’ Lewis guns were taken away from them and replaced with the questionable French Chauchat automatic rifle and the Hotchkiss heavy machine gun. Although, at the time, the Marines were furious at this the turn of events, in hindsight, the change is understandable. Maintaining a supply of replacement parts for Lewis guns would have been more than difficult for the single brigade of Marines within an Army division, and that division being one of at least 40 divisions within the Services of Supply for the entire American Expeditionary Forces. Moreover, Lewis guns were badly needed by the fledgling U.S. Air Service in France, and the Marines’ Lewis guns were used to arm observation biplanes. Marines in the infantry battalions were then issued the French 8 mm M1915 Chauchat light automatic rifle, and while some Marines grudgingly approved of it, others reviled it. Due to its ungainly and utilitarian appearance, some claimed that it had been made of recycled sardine cans. The open sides of the semi-circular magazines admitted dirt, and the automatic rifle was not well set up for accurate marksmanship. Worse, if not held correctly, it could bruise the gunner’s face while firing. Nevertheless, it provided the Marine squad with “walking” fire in an assault and served its purpose throughout the battles of Belleau Wood, Soissons, Saint-Mihiel, Blanc Mont and the Argonne, until being replaced in November 1918.

Marines enthusiastically embraced the M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle, commonly known as the “BAR,” when it was introduced into the American Expeditionary Forces in the autumn of 1918 to replace the Chauchats. Although BARs were not formally issued to Marines until a few days prior to their attack across the Meuse River during the Argonne campaign—and then used literally on the last night of the war—Marines had “borrowed” BARs from the Army’s 36th Division when they fought alongside the soldiers at Blanc Mont, a few weeks before. Marines put the selective-fire rifle to good use during the battle. Firing the standard service rifle cartridge from a 20-round detachable magazine, the BAR gave the extra firepower needed, and was much more reliable—and manageable—than the French Chauchat.

The Marines continued using the M1918 BAR throughout the campaigns in the Caribbean and Central America in the 1920s and 1930s, and had even more success with its successor, the variable-fire (300 or 600 r.p.m.) M1918A2, in World War II and the Korean War, until it finally was phased out shortly before the Vietnam War. Drawing on experience gained on street patrols in Shanghai during the 1930s, the Marines developed the four-man “fire team” concept, and reorganized its infantry squad tactics around the BAR in the later Pacific island campaigns of World War II.

In addition to receiving automatic rifles at the platoon level in the Brigade’s six infantry battalions, the machine gun companies of both the 5th and 6th Regiments, as well as the entire 6th Machine Gun Battalion, were issued French M1914 Hotchkiss machine guns, chambered, like the Chauchats, in 8 mm French Lebel. The tripod-mounted Hotchkiss guns were air-cooled, and fired 24 rounds from a metal clip that fed horizontally through the feed mechanism. This type of feed strip was also used on the obsolescent Benét-Mercié machine rifles, and was later used on several types of Japanese machine guns in World War II.

Like the “One Pounder” 37 mm M1916 Puteaux guns that were held by the regimental headquarters companies, the Hotchkiss guns were carried to the front lines by mule power, but then man-handled into battle. Thankfully, the introduction of the famous Browning M1917 .30-cal. machine gun (that the 4th Brigade received just after the Armistice), paved the way for man-powered machine gun carts, again based on Cole’s original design. While the Puteaux gun subsequently only saw service in the Marine Corps up to the outbreak of World War II, the Browning heavy water-cooled machine gun served Marines well through World War II, the Korean War and through the 1950s.

Another firearm that lasted in Marine Corps service for years after World War I was the shotgun. In fact, modern versions of it are still issued to select Marines today. Just before the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, in September 1918, some Marines were issued the pump-action, five-shot, 12-ga., Model 1897 Winchester shotgun, or as it was termed in its military designation, “Model of 1917 Trench Shotgun.” This short-barreled version of the popular American hunting shotgun was fitted with a ventilated, stamped-steel handguard over the barrel, which in turn, was fitted with a bayonet lug that accommodated the bayonet designed for the M1917 Enfield rifle. While they ostensibly were intended for use in guarding prisoners of war, Marines found them to be an excellent arm in the assault, when loaded with 00 buckshot. The German government lodged a formal complaint, claiming that the use of shotguns violated the international Hague Convention of 1899, which banned non-jacketed bullets. However, the same convention also banned the use of poisonous gas—and the Germans developed, and first employed, poisonous gas in 1915. The Americans, therefore, did not take the German protest very seriously.

By the end of the war, the Marine Corps had proved its value on the battlefields of the Western Front many times over—using the aforementioned arms. Very fortunately, and thanks to the ongoing efforts of the NRA, collectors in the United States are still able to own operable examples of these historic firearms of World War I, unlike the case with military history enthusiasts in many countries around the world. These firearms are the tangible relics of stories of bravery and sacrifice, and they truly are the guns that made the world in which we live today. Museums and public institutions cannot preserve enough of them for future generations, so hopefully, enough of them will survive among private collectors for study and appreciation for years to come. If you think that one of the guns mentioned above is in your gun cabinet at home, please don’t trample the family dog in your rush to check its serial number!

The authors thank the staff of the National Museum of the Marine Corps (especially Joan Thomas), the Marine Corps History Division (especially Kara Newcomer), and NRA Life member Glenn E. Hyatt for their assistance in the preparation of this article.

(Editor’s Note) Ken Smith-Christmas, a frequent contributor to American Rifleman and commentator on “American Rifleman Television,” served on the staff of the Marine Corps Museum for nearly 30 years, and brought Mark Henry, author of several volumes in the “Osprey” series (including one about Marines in World War I), onto the museum staff in 2003. Together, they played an instrumental role in the conception and development of exhibits in the National Museum of the Marine Corps, 18900 Jefferson Davis Highway, Triangle VA 22172; usmcmuseum.org.