Despite the ongoing attacks on our Second Amendment rights, we gunners are actually pretty blessed with an array of accessible firearms. Modern manufacturing capabilities and new lightweight and extremely strong materials can be made into guns that only existed as a dream a generation ago. But with so many guns on the market, it can be a daunting task to find the right one to get started. Take handguns, for instance.

New handguns are introduced throughout the year, and every manufacturer tries to tout each new gun as the answer to a vision of the ultimate pistol or revolver. It’s called business, and we couldn’t get along without it.

Nevertheless, the beginning handgunner can easily be inundated with marketing speak and then find themselves in an untenable position of trying to learn to shoot a gun that they probably can never truly master because the pistol does not properly fit him or her. Much is written and videoed about rifle and shotgun fit, but handgun fit is largely ignored. Consequently, many people who go to a gun store looking for their first handgun find they are overwhelmed.

The author's relatively short fingers cannot properly reach the trigger of many double-action or striker-fired semi-automatics, thus he carries a Model 1911 like this custom Colt Commander from Novak’s.

Handguns are small, relatively lightweight and have limited points of contact with the shooter, thus they can take longer to master. Even a rimfire handgun can be a problem if the shooter cannot maintain a consistent and repeatable grip on the gun. Whether simply handling the gun, acquiring a sight picture, shooting it, controlling and recovering from the recoil and reacquiring the sight picture, all of these tasks are demanded of relatively long, unsupported limbs with multiple joints, quivering muscles and jittery nerves. It only makes sense that the gripping surface of the handgun be in intimate contact with the shooter’s hands. If you still think this is much about nothing, consider the competitive slow-fire shooter. His or her stocks are often custom made to fit their hand and full of swells and curves mimicking the profile of their hand in order to maximize the contact surface and minimize movement. Such stocks are not practical for an everyday carry or even a hunting handgun, but that doesn’t mean that we can’t do as much as possible to make the handgun fit our hand(s).

When the single-action revolver debuted, the grip frame and stocks were pretty basic. The grip frame is shaped much like an old plow handle. Besides being wickedly elegant, it was and is a remarkably efficient shape given the way a single-action revolver is deployed. The rounded plow handle tends to rotate in the hand during recoil and does a couple of things. First, the recoil energy is dispersed making it less punishing, especially in heavier chamberings.

Secondly, the hammer is positioned right where it needs to be to be re-cocked should an additional shot be necessary. The size and shape of the classic Colt SAA grip and its subsequent clones is almost universal because of the way the revolver is handled during shooting. Since trigger movement is minimal to fire the revolver, there are no issues with the distance between the web of the shooting hand and the position of the trigger finger pad, unless your hand is exceedingly large and you have very long fingers. If that is the case, to correct that, there are plenty of aftermarket grip or stock makers who can create an oversized set of stocks.

However, the problem becomes more complex with double-action revolvers and semi-automatic pistols—whether double action or striker fired. With these handguns, the trigger must travel a longer distance in order to discharge the gun, and that trigger must be thoroughly controlled throughout its travel. Too, if the pistol has a double-column magazine or the frame of the revolver is quite large, it can be difficult for a person with shorter fingers to position the piece in their shooting hand to properly address the recoil. What usually happens is that person must rotate their shooting hand in such a way that their thumb is forced to absorb the recoil of the gun. This is a poor choice at best. First, it can be painful if the pistol or revolver is chambered in a powerful cartridge. And even if it isn’t, the movement of the thumb during recoil is an impediment to accuracy because it introduces an inconsistency in the way the gun is gripped.

Larger hands with long fingers allow some shooters a wider latitude of pistols to choose from. While the author's hand (top) doesn't quite offer a proper fit, the other shooter (bottom) has enough reach to center the trigger on the first pad of his trigger finger despite the double-column magazine of .45 ACPs in his Heckler & Koch USP pistol.

I have a very good friend and shooting buddy who is blessed with hands along the size of a fielder’s glove. He can wrap his fingers around the outsized—at least for many of us—grip frame of a double-column, .45-cal. H&K USP pistol as if it were designed specifically for him. Yet if you hand him a small-framed revolver, like a Smith & Wesson J-frame with the standard skimpy stocks, it will rattle around in his big old paw like a pea in a barrel. The handling difficulties this introduces is just as frustrating as it is with the petite gal trying to manage a double-wide Glock. I have short, thick fingers aboard a fairly wide but thick palm. This makes a Glock a non-starter for me. That’s not the fault of the Glock, it’s just my bad luck in the hand gene department. For that and another reason, I have to stick with my tried-and-true 1911s—and they must have the old short trigger.

With the double-action revolver, a similar problem exists. The distance between the rear of the grip frame where the web of the shooting hand goes to the center of the trigger at rest—the length of pull, if you will—determines to a large extent whether you will be able to handle and shoot the revolver effectively. A revolver’s stocks can be made thinner or thicker to a point to make it easier to handle the piece, but the overall distance of the grip frame to the trigger sets the parameters.

Standard target stocks are just too much of a good thing for the author. Note how just the tip of his finger makes it to the trigger.

An N-frame Smith & Wesson with factory target stocks is almost impossible for me to handle with my thick palm and digits. For years I fiddled and fidgeted with aftermarket stocks. In my effort to be able to properly address the trigger, I searched for stocks that were considerably thinner than factory target ones. Some were so thin that recoil in my .44 Magnums became painful. Now with custom stocks from Herrett’s, I have found the best compromise. It still is a bit of a stretch, but I am able to manage it.

With custom-made stocks built to fit his hand, the author is able to shoot large frame guns like this Smith & Wesson .44 Spl. Handgun fit is critical in being able to learn how to control and manipulate the gun.

When it comes to the very popular small revolvers—epitomized by the Smith & Wesson J-frame—the opposite problem arises. The tiny grip frame of these revolvers means that contact with the shooting hand—especially in the palm where most of the recoil should be addressed—is minimal. This makes controlling these little gats a real problem, even more so when powerful +P ammo is used. Again, aftermarket stock makers come to the rescue. The best I have found come from Craig Spegel. His Boot Grip completely redefines the handling characteristics of my J-frames. Be forewarned, however, Spegel is often backordered, so getting your pocket revolver suitably cloaked may take a while.

For most men and a lot of women, the factory round buttstocks on Smith & Wesson J-frame revolvers are too skimpy to allow the shooter to control the gun. Craig Spegel’s Boot Grip stocks fill the palm providing more surface to distribute recoil and establish better trigger control.

The last consideration for handgun fit is the angle of the grip relative to the line of the barrel. When double-action revolvers and semi-automatics were first produced, American gun makers believed—correctly, in my not-so-humble opinion—that handgun shooters would naturally want their guns to shoot as if they were pointing their index finger toward the target with a straight and locked wrist. Smith & Wesson and John M. Browning both found that a grip angle of 118 degrees from the centerline of the barrel to be the most comfortable and natural angle. With this angle, the piece comes up and the sights are immediately visible and ready for fine adjustment onto the target.

H&K P7 and Glock 19

The Europeans, of course, are different. Georg Luger, the folks at Steyr, H&K with its P7 and Gaston Glock insist that a sharper angle of 122 degrees to be better. Browning played with the notion with his .22 Automatic—later to be called the Colt Woodsman—but returned to his original angle for the P35 Hi Power pistol. Fact is, you can learn to shoot either well, which is likely a statement to the resiliency of humans rather than any “magic angle.” I still prefer the 118-degree grip angle on my 1911s. Could I learn to adjust to a Glock? Probably, but after shooting with a locked wrist for nearly 50 years, I simply do not want to relearn how to shoot a pistol. As they say, your mileage may vary.

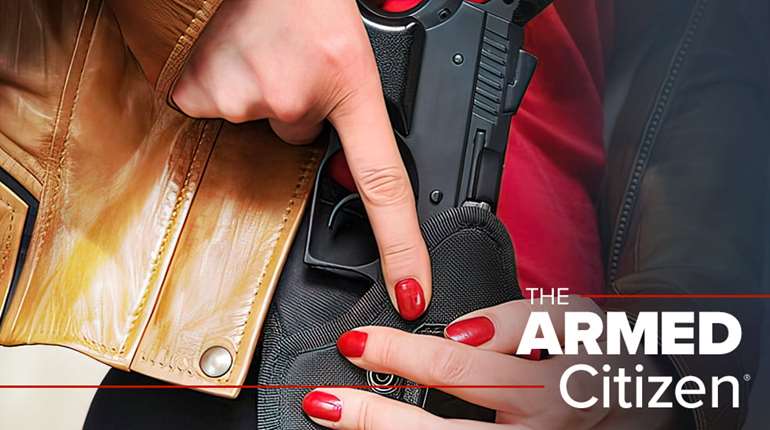

Those of you preparing to purchase your first handgun—revolver or semi-automatic—or who may be assisting a friend or significant other with their first purchase, would be well advised to pay more than casual attention to the fit of your prospective purchase in your hands. That striker-fired, double-wide semi-automatic that carries half a box of cartridges in its magazine may be what the cool kids are packing, but if you cannot wrap your hands around it enough to control it—especially under the stress of a fight—perhaps another pistol may be in order.