Originally published in American Rifleman, September 1991

By Charles E. Petty

I write this less than a year and a half after the announcement, at the 1990 SHOT Show, of the creation of a new cartridge, the .40 Smith & Wesson. In those early days, ammunition was the private patch of Winchester, which had collaborated with S&W in development of the cartridge.

In fact, I had .40 S&W ammo long before I had a gun that would shoot it. But the events of the last year have flown in the face of ammunition history.

Most new cartridges progress slowly, and we don't have to look far back in history to find examples of the way things typically work. For every splashy success like the .243 Win. or 7 mm Rem. Mag., there is a clinker like .256 Win. Mag. or 5 mm Rem. Mag.

Consider the .45 Win. Mag., 9 mm Win. Mag., the .32 H&R Mag. or the .357 Rem. Max. Each was produced by a single manufacturer and still is…and none can be called sparklingly successful, although the .32 H&R Mag. is doing better now that: there are a couple of different guns that shoot it.

Ammunition manufacturers usually adopt a "wait and see" attitude toward new rounds because the costs of tooling and development are high and, after all, they're profit oriented. If they can't predict reasonable sales, they aren't interested.

So the comparison of new guns to new ammunition is often a chicken-and-egg question. Gunmakers aren't interested in producing something for which you can't get ammunition; and ammo makers, logically, don't want to produce ammunition for which there are no guns. As both wait to see what everyone else is going to do, it isn't unusual for decades to pass.

The .40 S&W. by contrast, has experienced phenomenal acceptance. By the time of the 1991 SHOT Show, every major American ammunition manufacturer had one or more loads either in production or scheduled, and gun companies adding it to their lines were almost too numerous to count. How, in an industry that frequently moves at a pace snails would find slow, does a combination get on the fast track? There are a lot of reasons, but I think much of it gets back to the FBI space program.

Without repeating the whole long story, the FBI began a series of ammunition, tests and concluded that a reduced load for the 10 mm Auto firing a 180-gr. bullet at 950 (later 980) f.p.s. was the choice for a new pistol for the nation's premier law enforcement agency (June 1990, p. 35).

The FBI tests showed that a heavy, large-diameter bullet had a better chance of penetrating deeply enough to insure that vital organs or major blood vessels were struck. A wound ballistics seminar found that this is the single most important element in handgun wounding effectiveness, a change from theories of the 1970s.

Some credible medical evidence suggests that the theory of temporary wound cavity size is not meaningful in predicting the outcome of an armed encounter where handgun velocities are involved. Direct trauma and associated blood loss are much more important.

The small, light bullets that enabled the 9 mm to produce large temporary wound cavities did not have the ability to penetrate deeply enough to perform well in the FBI test series course.

The most important factor in the .40 S&W’s dramatic ascendance is that it duplicates the ballistics of the FBI’s chosen 10 mm load in a smaller firearm package. (See “Top Cop Cartridge,” August 1991, p. 50)

The FBI ammunition study convinced many that a bigger bullet moving at relatively sedate velocities is more effective than a light bullet that moves much faster. Of course, not everyone agreed with that conclusion and a heated, sometimes bitter, debate ensued and continues.

The evidence suggests, however, that the arms and ammo manufacturers have concluded that something must be right about the combination, and they have jumped aboard the .40 S&W bandwagon with remarkable speed.

What's right, as I see it, is not any one attribute of the gun or ammo, but the combination of a cartridge of significant caliber fired from a pistol whose size is comfortable for most shooters.

The 1980s was the decade of the "wondernine" as a whole class of pistols chambered for that cartridge evolved from bulky, inaccurate things to sleek, comfortable pistols.

Shooters have learned to love them and manufacturers have responded by offering us a nearly bewildering variety of pistols that have either size or magazine capacity as their primary selling points. How¬ever, more than a few authorities have questioned the 9 mm's ability to produce rapid incapacitation of a human target.

Just about anybody with more than a passing interest in pistols immediately noticed the similarity between the FBI's 10 mm "lite" and the .45 ACP, and many a gunshop ballistician has denigrated the choice on those grounds.

The FBI's reason for rejecting the proven .45 was that it was, in the words of one official, "topped out developmentally" after 80 years of use. The potential of the 10 mm, on the other hand, is just beginning to be explored.

This point leads to perhaps the largest negative in the .40 S&W story. While the developmental goal—to duplicate the FBI 10 mm load in a package suitable for use in a smaller pistol—was met, the cartridge that came about is also at or near the maximum pressure and recoil levels that can be accommodated by pistols of the appropriate size and design.

The reduction of case capacity leads to generally higher pressures, and the .40 is emphatically not a small 10 mm. While I am sure that somewhat higher velocities may be attainable, handloaders who think of the .40 as a candidate for hotrodding should put that notion aside. Pressure for the .40 S&W cartridge has been standardized by SAAMI at 37,400 p.s.i.

Perhaps the largest appeal of the .40 S&W lies in the law enforce¬ment community. The ink was hardly dry on S&W's announcement before the first major agency, the California Highway Patrol, announced that it was adopting the cartridge and the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division (SLED) quickly followed.

The Charlotte (N.C.) Police Department became the first large municipal agency to purchase. .40 S&W pistols (see May 1991, p. 24). Then the U.S Border Patrol adopted it as well. Small agencies adopted the round or permitted their officers to purchase pistols chambered for it, and rumors flew that an-other major Federal agency would switch. That one has yet to materialize, but there is little doubt that large numbers of agencies are interested.

Two of the few negatives that the law enforcement community faced were the avail¬ability of and the cost of ammunition, but these problems have diminished. Many law enforcement agencies now require their offi¬cers to qualify with duty ammunition, but many use reloads or less expensive factory ammunition for training.

The first generic .40 S&W ammunition is now available from Winchester in the form of a 180-gr. full-metal-jacket (FMJ) load that duplicates its more expensive hollow-point (HP) ammo, and CCI has a considerably less expensive 180-gr. plated hollow-point (PHP) load in its Blazer line of aluminum-cased ammunition. Federal has just announced a '"training" round for the .40 S&W that uses a swaged lead 180-gr. semi-wadcutter (SWC) bullet. It is only a matter of time before commercial reloaders can provide the quantities needed for training.

Although the cartridge's supporters are legion, there are also detractors who raise some valid questions. How, they ask, can anyone adopt a cartridge that is un-proven on the street?

I think this is a reasonable concern, but there is nothing in any of the tests I've reviewed to suggest that there will be problems. How a bullet will perform in an actual shooting situation is diffi¬cult to predict because ho two are alike. There well may be "failures" but these must be carefully studied in terms of medical evidence before any conclusions can be drawn.

The FBI uses very stringent test methods that stress a bullet far more than most actual shootings, and it finds a "success rate" of 87.5 to 95% for the .40 S&W loads they've tested to date. The top performer was the Federal Hydra-Shok (95%), followed by the same firm's 180-gr. jacketed hollow point (JHP) (90%) and Winchester's original load at (87.5%). There already have been a couple of actual shootings, and the information I have is that the cartridge performed as predicted.

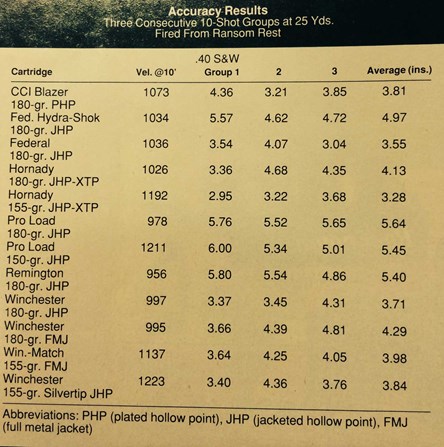

In order to evaluate the accuracy of the loads now available, I tested all that I could by firing three 10-shot groups at 50 yds. from a Ransom rest. The test pis¬tol was the new "Tactical Pistol" from Smith & Wesson's Performance Center. This is a custom shop headed by Paul Liebenburg and John French that will provide specialized pistols and revolvers for the members of Team S&W as well as the general public.

The Tactical Pistol looks very much like the Model 4006 but is actually built on a different frame and slide that are made to the specifica¬tions of the Performance Center and are somewhat oversized to allow for proper fitting.

The pistol uses a 5" Bar-Sto barrel and a novel spherical barrel bushing. When I first shot the pistol at 25 yds. from a sandbag rest, it delivered very good groups, and I elected to use it for the more exhaustive test. The 5" barrel accounts for the velocities being slightly higher than those readers may have seen published previously.

The first available Tactical Pistols will be sold exclusively by Lew Horton Distribution Co., but they will eventually also be available from the Performance Center.

Twelve different loads were tested for accuracy in the Tactical Pistol, and the results are presented in the accompanying table. The average accuracy was 4.34" for all loads tested, and if there is a surprise in the data, it is that no single load emerged as a clear-cut winner.

The "smallest average came from the Hornady 155-gr. JHP, followed very closely by the Federal 180-gr. JHP.

The primary use of the .40 S&W cartridge is, at least for now, as a law enforcement and defense round. It may find a place in International Practical Shooting Confederation (IPSC) competition somewhere down the road, but is already in use on the streets of the nation by more than 50 law enforcement agencies.

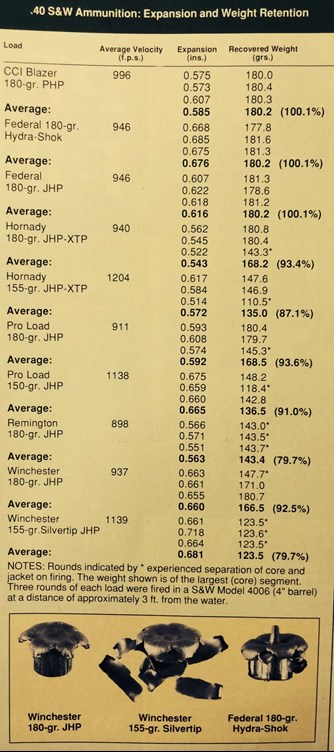

While it would have been nice to evaluate the incapacitation potential of the many hollow-point rounds using the methodology established by the FBI, it simply wasn't possible for this story. In¬stead, I elected to measure expansion by firing three test rounds into water.

While ballistic gelatin may be a better test medium, it is not without draw¬backs, not the least of which is the time and cost required to produce the quantities of gelatin blocks needed for a comprehensive test of this nature. My experience has been that a bullet that expands well when fired into water will probably expand almost as well in tissue or gelatin, but a bullet that does not expand in water will almost surely fail to expand in flesh. The flaw with water as a test medium is that there is.no easy way to measure penetration.

I was able to fire a few rounds of Federal Hydra-Shok ammo into bare 10% gelatin, and when the expanded diame¬ters of those were compared with the bullets fired into water, I was surprised to learn that the bullets fired into gelatin actually expanded a little more (0.699") than did those fired into water (0.676").

I doubt that the difference is significant, but my confidence in the use of water to judge bullet expansion was bolstered. It certainly won't take the place of gelatin but seems to be suitable for this sort of investigation. Besides the lack of penetration data, the only other problem is that you get wet.

The other important factor in judging bullet performance is weight retention. A bullet that fragments on impact loses so much energy in the process that it may not be able to penetrate adequately. In this case, water is an excellent test medium because it provides greater resistance and, therefore, is more likely to pro¬duce bullet fragmentation than tissue. A bullet that expands well in water and retains most of its weight is likely to be effective.

Weight loss was sometimes caused by the jacket separating from the lead core, but there were a few cases where only a portion of the jacket separated. All the hollow-point bullets currently available for the .40 S&W have some form of scoring at the nose where lead and jacket material meet. This scoring is to promote expansion, so there were several instances where one "petal" of the jacket peeled back and was lost.

For the purposes of this test, three rounds were fired and the recovered bullets measured for expansion by taking three equidistant diameter measurements and then averaging them, since expansion is sometimes uneven. The recovered bullets were weighed, and those numbers were also averaged.

Although fragments were recovered, they were not included in the weight if they were completely separated.

The percentage weight retention was calculated based upon the published bullet weight, and it is important to note that those numbers are nominal, ex¬plaining how some bullets actually "gained" weight. The expansion test was fired using a standard S&W Model 4006 pistol with a 4" barrel, and those velocities are also included in the table.

In addition to the loads tested, there are several other specialty loads avail¬able in .40 Smith & Wesson. These fall into the category of "prefragmented" bullets such as the Glaser Safety Slug, MagSafe and the Genco Core Shot which use a charge of shot in place of the conventional lead core.

Because of their extremely high cost, these were not tested. The only one with which I have any experience is the Mag-Safe 84-gr. “Defender” load, which uses No. 2 shot instead of the smaller sizes used in the other loads.

I was able to chronograph a small sample of these and read velocities of 1756 f.p.s. from the 4" barrel of an S&W Model 4006. These are specialty .loads not intended, or suitable, for everyday use. In addition to these, Black Hills Ammunition offers two 40 S&W loads with 155- and I80-gr. bullets, but I was not able to obtain these in time.

I have been fortunate to participate in the testing of the .40 S&W from the beginning, and I've never seen anything like it. Nothing I've seen can compare to the pace of development the shooting world has seen in the .40 S&W story.

Even though the evidence suggests that the 40 S&W is, indeed, one of the best possible choices for law enforcement, we must be careful not to taint it with the "magic bullet" brush. No cartridge can provide a substitute for adequate marksmanship skills.