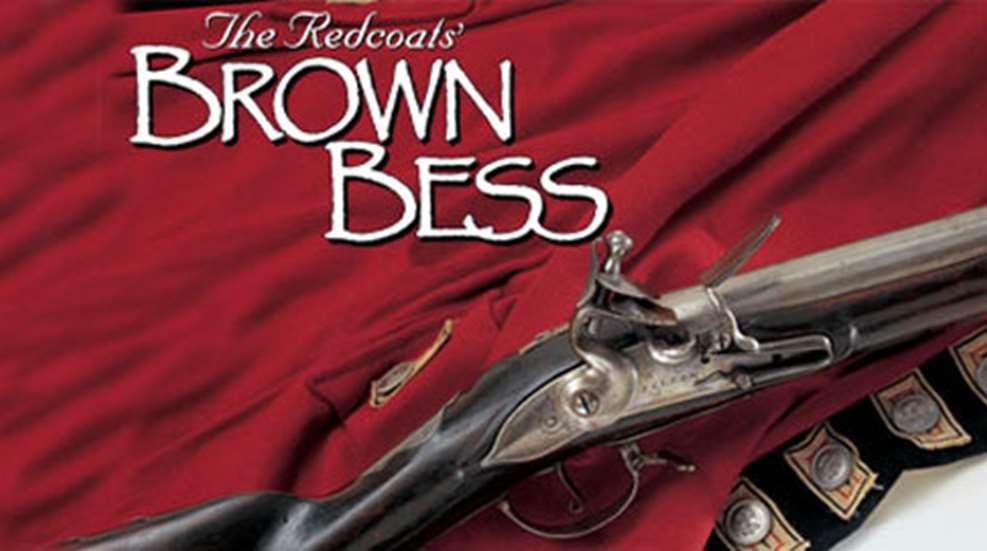

It began with a contract by Britain’s Royal Board of Ordnance dated September 15, 1714. The document’s purpose was not to authorize additional arms, but to develop a system of manufacture and control. The board would accumulate components of a new standard longarm pattern and inventory them at the Tower of London armory for release to private contractors in time of need. They, in turn, would provide the stocking and finishing of the final arms in conformity with a prototype musket (usually bearing an official wax seal). Locks, barrels and other iron components were to originate largely from Birmingham, while most brass furniture, stocking and assembly would be centered in London. All of the parts would then be subjected to close quality and tolerance inspections by the Board of Ordnance.

The new procedure was a brave attempt to remedy the chaos of arms diversity that England faced at the conclusion of the war of the Spanish Succession in 1713. Unfortunately, it challenged some of the most powerful groups in highly stratified English society. The majority of army regiments were controlled by colonels who were important private individuals with established economic and political power. Each would be given governmental funds to recruit, equip and maintain a regiment. Any money remaining was considered his to keep. Prior to this date, the colonel was constrained only by vague requirements limiting barrel length and bore size for his regiment’s longarms. As a result, he arbitrarily chose among a wide range of domestic and foreign patterns of varying quality and price.

Further opposition came from the entrenched, private London Gunmakers’ Company that saw this change as a threat to its traditional control of the design, specification and production of England’s existing arms industry.

As might be expected, the new system was strongly opposed and then deliberately ignored. Nevertheless, the board’s patient yet focused efforts finally resulted in a new musket design in 1722 called the “King’s Pattern.” Resistance to the new discipline along with the absence of wartime pressures delayed its production until 1728. The new standard musket that ushered in England’s organized ordnance control was first issued in 1730 as the “Long Land” pattern. It was the beginning of the famed “Brown Bess” series that would become a legend through its contribution to the winning of Britain’s empire and to America’s eventual freedom.

Firearms Capabilities:

The 18th century musket was essentially a large smoothbore shotgun. After loading from the muzzle with loose blackpowder and a round lead bullet from a cylindrical, paper-wrapped cartridge, the musket was fired by the flintlock action above the trigger. A rotating cock holding a piece of flint snapped forward to strike a pivoting L-shaped frizzen or “steel.” That action created sparks that ignited a small portion of priming powder in a projecting flashpan sending flame through the barrel’s touch hole to reach the main charge. Obviously, it would not perform in the rain and depended upon a sharpened flint and properly hardened steel frizzen for reliability.

The real problem, however, was the blackpowder quality. Follow-ing each firing, roughly 55 percent would remain as a black sludge that built up inside the barrel clogging the touch hole and coating the lock. To cope with this fouling residue, the average ball was four to six hundreds of an inch smaller than bore size. Upon ignition, the undersized ball bounced and skidded up the barrel and proceeded in a direction determined by its last contact with the bore. Beyond 60 yards, the ball would lose its reliability to hit a man-size target.

These limitations determined 18th century battle tactics, which employed long lines of men trained for speed of loading rather than accuracy. They were expected to average four rounds per minute. The soldiers typically pointed their arms and fired in controlled volleys at enemy troops positioned 50 to 60 yards away. The typical battle was decided by a disciplined bayonet charge ending in a hand-to-hand melee.

To meet these combat conditions, the new British Brown Bess standard musket was designed to deliver a large bullet at low velocity. It employed a sturdy stock for use as a club in close fighting and had an overall length that combined with a long, socket bayonet to create a spear or pike for impacting an enemy’s line. It was also designed to be durable and to withstand the rigors of years of active campaigning. The Brown Bess was to successfully fulfill all of these demands.

Britain’s military long arms during the 18th century were officially considered in two groups: Land Service and Sea Service. We are concerned with the former. The unofficial term, “Brown Bess,” has various claims for its origin, but a mention in the April 2-9, 1771 issue of the Connecticut Courant verifies the name’s acceptance in America preceding our War for Independence.

The basic Brown Bess musket mounted a round, smoothbore, .75-cal. barrel on a walnut “heart wood” stock held by a vertical screw through the breech plug tang plus lateral cross-pins that pierced tenons brazed to its underside. The upper stock terminated 4 inches below the muzzle to permit attaching a bayonet. A rectangular top stud behind the muzzle secured the bayonet after sliding through slots in the socket and also functioned as an aiming guide. There was no rear sight.

Its butt included a round wrist extending back to a handrail form beneath the comb. The ramrod, in turn, slid into a bottom stock channel and was retained by four pipes. Just below the bottom pipe was a stock swell intended as a forward “hand hold.” All of the attached accessories (or furniture) were of cast brass. The two-screw lock had a rounded base plate that mounted a swansneck cock. Two swivels for a shoulder sling were also included. Its weight totaled 10 to 11 pounds.

Like the soldiers who fired them, traditional British arms designs were known for their consistency. These fundamental features would persist until the late years of the 18th century despite an interim reduction in length and a gradual simplification of the lock and furniture. Official control and proofing sources for the King’s arms were the Board of Ordnance at the Tower of London and the less disciplined Dublin Castle armory supplying troops in the “Irish Establishment.” During war-time, supplementary contracts were often made with continental European manufacturers. Similar muskets approximating this design were also ordered directly from private contractors in England by some British regimental colonels, local militias, private trade organizations and various American colonies.

The Brown Bess patterns employed in the Revolutionary War are best considered in two categories that are most easily identified by their barrel lengths: the 46-inch “Long Land” and the 42-inch “Short Land” muskets. They are also named by some modern collectors as the “First” and “Second” patterns. (A “Third” pattern is often included, but refers to a 39-inch-barreled musket privately produced in England for the East India Co. Army in India. It did not officially reach America during the Revolution, but it was finally adopted by the British government in the 1790s.)

Long Land Brown Bess (“First Pattern”):

There were three fundamental variations of this first category: the 1730, 1742 and 1756 patterns.

Long Land Pattern 1730:

Considered the first of the Brown Bess series, it included a 46-inch barrel (.75 cal.) with a baluster-shaped breech pinned to a walnut stock, a curved banana-shaped, rounded lock bearing a single (internal) bridle, heavy brass furniture, a wooden ramrod, plus raised stock carving around the lock and sideplate. The arm was issued without a nosecap, although some regiments added a brass end band. Its total length was approximately 62 inches. After the War of Jenkins Ear commenced in 1739, a special effort was made to replace most of the remaining non-conforming “colonel’s” muskets with this 1730 design.

Long Land Pattern 1742:

As the fighting expanded into the War of the Austrian Succession (ending in 1748), this updated version added an exterior bridle joining the lock’s flashpan and frizzen screw, introduced a new trigger guard, reduced the raised stock carving, and defined the final beavertail shape carved around the barrel tang. Its basic form remained unchanged. These 1730 and 1742 Patterns were the primary British infantry firearms used in America during the French and Indian War (1754-1763).

Long Land Pattern 1756:

In the late 1740s, further improvements were initiated based upon wartime experience. They were incorporated into this last of the three Long Land Brown Besses and included: a steel button-head ramrod now accompanied by a lengthened 4-inch upper rammer pipe having a flared front opening; the former banana-shaped lock was straightened along its bottom edge; and the raised stock carvings (including the forward hand hold) were further reduced. A cast brass nose cap at the end of the fore-end was also adopted. The 1756 Long Land musket experienced most of its North American usage in the Revolutionary War.

Short Land Brown Bess (“Second Pattern”):

This second and shorter of the two Land Pattern categories is best defined in three stages: The Marine or Militia, 1768 and 1777 patterns.

Marine or Militia Pattern 1756 and 1759:

The need for a lower cost musket to arm the Marines and English militia led to the adoption of this arm in 1756. It retained the Brown Bess form, but reduced the barrel to 42 inches (still in .75 cal.), used a wooden ramrod and economized further by omitting the nose cap, tail pipe and escutcheon. Moreover, the rounded sideplate shape of the Long Land design was now flattened while the prior 6-inch long brass butt tang was shortened to 3 3/4 inches and included a distinctive upper screw head. In 1759, it was upgraded by replacing the earlier version’s wooden ramrod with a steel button-head form and adding a tailpipe, nose cap and lengthened upper pipe.

Short Land Pattern 1768:

The British infantry was already leaning toward a shorter arm. (Many 4-inch sections of sawed-off Long Land barrels have been excavated from French and Indian War sites.) Impressed with the success of the Marine or Militia musket, they adopted the 42-inch barrel to create a new Short Land standard infantry Brown Bess in 1768. This configuration retained many features of the previous Long Land Pattern 1756 design, but with the reduced 42-inch barrel length, flattened side plate, shortened butt tang (no top screw) and reduced stock carving.

Short Land Pattern 1777:

As an adjustment to wartime demands, two changes were authorized for the Short Land Brown Bess in 1777. A less expensive lock then specified for the private East India Co. was adopted and the second ramrod pipe was changed from the previous barrel shape to a straight sloping profile with an expanded front opening (“Pratt’s Improvement”) already in use.

The Brown Bess’s Role in the American Revolution:

As with any country suddenly involved in a war, the American Colonies in 1775 had to acquire a great number of arms quickly. Their immediate supply was already in the militia system of each state that required men from 16 to 60 years of age to own a longarm plus a bladed secondary arm such as a sword, bayonet or belt axe. Those and other flintlocks they pressed into service included a broad mixture of various locally made hunting and military designs using assorted old and new parts, commercial arms contracted from private makers, inventories of provincial arsenals, confiscated Loyalist arms, state purchases of spare guns from civilians, surplus supplies from European dealers and muskets issued here by the British during prior wars. These latter arms were largely obsolete and repaired arms, and in many cases were vintage Dutch, Liege and other European cast-offs. Thus, the few Brown Besses initially in American hands were usually worn versions of the early Long Land 1730 and 1742 designs, which were later supplemented by at least 17,000 more recent patterns captured during the conflict (Moller, Ref. 5).

The majority of locally manufactured rebel arms followed the English pinned barrel format prior to the heavy import of French and other European military aid beginning in 1777, which supplied most of the Continental Line for the remainder of the war. Yet the Brown Bess remained a major share of the arms carried by provincial forces through 1783—both as complete muskets and as surviving components remounted on the large number of locally assembled American arms.

At the beginning of hostilities, the Royal forces had at least 5,200 muskets in storage mostly in New York and Quebec (Bailey, Ref. 1,2). They were primarily wooden ramrod Long Land 1730s and 1742s. Most active British regiments here were equipped with the later 1756 version having the steel ramrod. Through the war’s first two years, the Long Land remained the primary British arm in America, and earlier wooden ramrod patterns were normally given to Loyalist units or as replacements to Hessian troops. Some Short Land muskets arrived early with a few of the new regiments from Britain, and they became the British army’s principal arm after 1777. The English carbines and fusils, although not covered in this article, usually adopted the Brown Bess configuration in reduced dimensions.

During the American Revolution’s eight years, England produced more than 218,000 Land Service longarms and contracted for another 100,000 of the Short Land Pattern 1777 from Liege and German sources after France entered the hostilities in 1778 (Bailey, Ref, 1,2). Created as the beginning of a new system for standardization and quality control, these venerable Brown Bess muskets became the workhorse that was instrumental in determining the future of North America and much of the world. Today, they remain as icons reminding us as collectors and historians of the courage and sacrifices during those formative years of our heritage.

Special appreciation is extended to Joseph C. Devine for his generosity in photographing the arms for this article at his J.C. Devine, Inc., facilities.