Henry Repeating Arms was founded in 1996 by the late Louis Imperato, and his son Anthony has been president of the firm since its inception. The company now ranks among the top five manufacturers of long guns in America, and it produces more center-fire and rimfire lever-action rifles than any other American company. Each year more than 500 employees produce in excess of 300,000 firearms at the Bayonne, N.J., and Rice Lake, Wis., factories under the slogan “Made In America Or Not Made At All.”

The company name comes from Benjamin Tyler Henry who, in 1860, completed the design of the lever-action rifle bearing his name. With a capacity of 16 rounds, it was a highly desired, although rather scarce, firearm during the American Civil War. The Henry is easily recognized by a number of features, including a brass frame and front loading of its tubular magazine.

Soon after Oliver Winchester bought the manufacturing rights to the Henry rifle, it was modified a bit and re-introduced as the Winchester Model 1866. After more improvements it became the Model 1873. All share the same toggle-link breechbolt locking system and, while not as sturdy as lever-action designs introduced from 1886 on, it was plenty strong for handloads and factory ammunition loaded to original blackpowder chamber pressures.

The New Original Henry

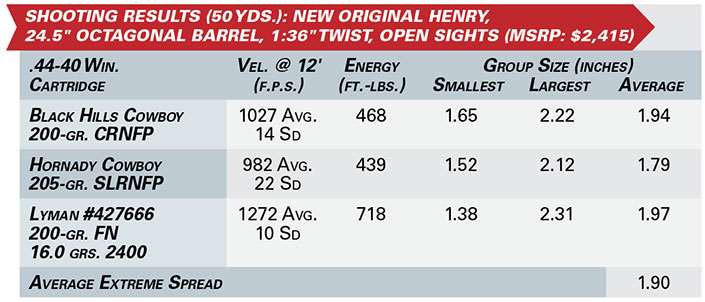

Rifles originally designed and manufactured in America and now being built in other countries are commonly classified as replicas. The Henry was designed and built in America during the 1860s, and a rifle being built to the exact same design and dimensions today by Henry is often described as the real thing. But there are differences. The 24.5" barrel of today’s version, called the New Original Henry, is chambered to .44-40 Win. rather than the long-obsolete .44 Henry Rimfire. Original barrel-groove diameter for the .44-40 is 0.427", but the Henry’s bore measures 0.429", matching the diameter of most .44-cal. jacketed bullets available today. A .45 Colt option was also recently added.

The New Original Henry was introduced in 2013, and building it is a costly operation, even on today’s computerized machinery. Whereas the tubular magazines of lever-action rifles are commonly made separately and then attached to the barrel, the magazine of the Henry is an integral part of its barrel. The machining operation starts with a bar of steel measuring about 26" long, 1.5" thick and 2" wide. Deep-hole drills are used to hollow out the magazine tube and to bore the barrel. Rifling is then formed inside the barrel by the button process.

The New Original Henry rifle, with hardened brass receiver, has a magazine capacity of 13 rounds of .44-40 Win. A new carbine version, with a 20.5" barrel, has a capacity of 10 rounds. A one-of-1,000 series of rifles was introduced in 2013 with Serial No. 1 bringing $83,000 at the NRA Foundation auction held during the previous year. They quickly sold out, and a second one-of-1,000 series was announced in 2015. The hand engraving replicates that found on Serial No. 18, built around 1862. A few of the original Henry rifles had iron receivers, and today’s “Iron-Framed” rifle is the same except for its steel receiver and casehardened finish.

Loading begins with turning the Henry upside down and hooking a thumb around the ovular tab of a spring-loaded brass follower riding in a full-length slot in the bottom of the magazine tube. After the follower has reached the limit of its forward travel, it is held there while a metal sleeve now containing the follower and its fully compressed follower spring is rotated far enough to expose the open end of the magazine. With the magazine filled, the sleeve is rotated back into position and the follower slowly released to apply pressure on the stack of cartridges. The spring is quite strong, and, if the magazine is only partially filled, the follower should be eased back against the cartridges rather than allowed to fly back with considerable force.

True to the 1860 design, today’s New Original Henry rifle has a half-cock notch on its hammer but no manual safety of modern design. Pulling the trigger and then releasing it while lowering the hammer puts it in its half-cocked position. Should the hammer be allowed to travel beyond that point, it will rest against the firing pin, and a blow on the hammer could cause the rifle to fire if a round is in the chamber. That design detail was used in lever-action rifles later built by Winchester, Marlin and other companies, and remained popular until the advent of the inertia-driven firing pin and the transfer-bar system. Despite a design going back more than 150 years, the accuracy of today’s New Original Henry is as good as, and sometimes better than, some more-modern lever-action rifles. It may also be the most fun to shoot.

The Golden Boy

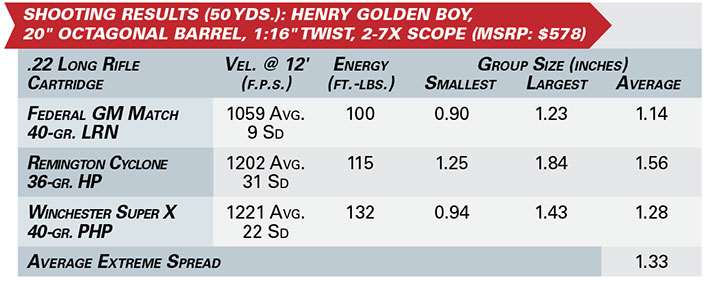

Returning to the beginning of today’s Henry Repeating Arms, the .22 rimfire Golden Boy was introduced in 1997 and is now available in three chamberings. Capacities are 16 rounds of .22 Long Rifle, 12 for the .22 WMR and 11 for the .17 HMR. Depending on the model of Henry rimfire, barrels are either round with a muzzle diameter of 0.590" or heavier octagon measuring 0.680" across the flats. Golden Boy barrels are either 20" or 20.5" long depending on the chambering. A .22 Long Rifle Golden Boy tips the scale at 6 lbs., 12 ozs. Henry offers youth and carbine rimfire models with 16.25" barrels, but not under the Golden Boy name.

Lockup of the Golden Boy action is identical to that of the Marlin 39A, and is accomplished by pressure exerted against the breechbolt by the forward end of the finger lever when it is closed. Its receiver consists of a light alloy casting enclosed by a thin metal cover, the latter with a brass-colored finish called Brasslite. The cover is held in place by four screws. The receiver is accessed for cleaning by turning out those screws, removing the buttstock and detaching the cover to the rear. The cover is a tight fit, and if a bit stubborn about budging, a light tap or two on its front end with a small rubber mallet will break it free without marring the finish. The curved buttplate and barrel band of the Golden Boy are solid brass. Henry’s standard rimfire rifles have a receiver cover, hard rubber buttplate and barrel band with a black finish.

The receivers of the black rifles have 3/8" grooves for scope mounting but the brass Golden Boy does not. A barrel-attached, cantilever-style base is available, but it positions a scope quite high above the receiver. That, along with considerable drop in the stock, prevents a shooter’s cheek from contacting the comb when looking into the scope. My guess is most who buy that model are traditionalists who prefer to stick with open sights as I sometimes do. Due to less drop in the stock and lower scope mounting, the “black” rifle is a better choice for those who prefer a scope, and the Varmint Express model features a raised comb.

I grew up shooting a Marlin 39A, and my standard procedure for unloading it is to first open the lever to remove a cartridge from the chamber with the lever remaining open during inner magazine removal. The magazine is then emptied, but a cartridge remains on the carrier of the action. Re-inserting the empty magazine, pointing the rifle in a safe direction and operating the lever several times removes that round and assures the rifle is totally free of cartridges. The same procedure works equally well for the Henry Golden Boy. Like the Marlin 39A, its hammer has what the company describes as a half-cock safety notch that should be used anytime a cartridge is in the chamber.

The Big Boy

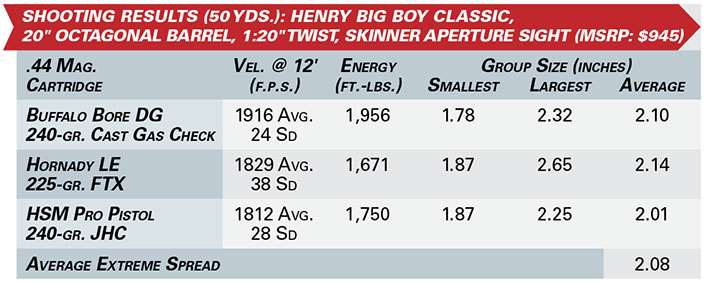

Moving up to center-fire rifles, we have the Big Boy introduced in 2003. It is available with blued, silver, color-casehardened and industrial-grade chrome metal finishes, but cowboy action shooters often prefer the hardened-brass receiver, which is said to be equal in strength. All steel-frame rifles come with quick-detach single swivel posts installed, but those with brass frames do not. With the exception of the New Original Henry, all center-fire rifles are drilled and tapped for scope mounting. For those of us who often use aperture sights on lever guns, Skinner Sights offers them for Henry rifles, and they utilize holes drilled and tapped into the roof of the receiver at the factory. I have several; the quality is top-notch, and I installed them on a number of the guns used during accuracy testing.

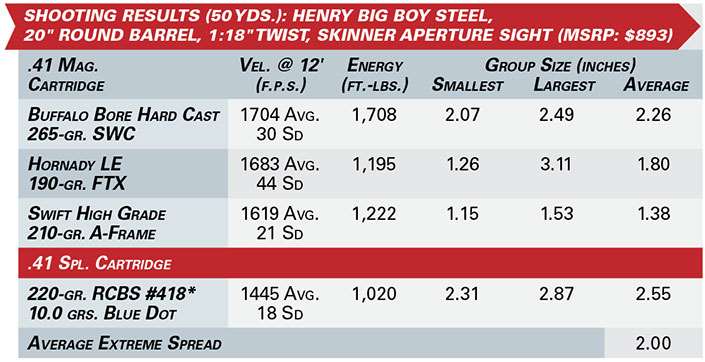

Big Boy chambering options are: .327 Federal Mag./.32 H&R Mag., .357 Mag./.38 Spl., .41 Mag./.41 Spl., .44 Mag./.44 Spl. and .45 Colt/.45 Schofield. The receiver is scaled to size for those cartridges and measures 2" tall and 5.75" from front to back (not including the upper tang). Receiver height is the same as for the Marlin 1894, but slightly greater length enables the Henry to handle loads with bullets seated to longer overall cartridge lengths. As an example, SAAMI maximum for the .41 Mag. is 1.590", but the Big Boy gobbles up the Buffalo Bore 265-gr. Hard Cast load measuring 1.705".

Standard Big Boy barrel lengths are 20", but carbine versions with 16.5" barrels and big-loop finger levers are also available. Overall weight of the rifle with 20" barrel depends on whether the barrel is round or octagonal, and what material the receiver is made of. The .41 Mag. I shot had a blued steel frame and round barrel, and it weighed exactly 7 lbs., while the brass-frame .44 Mag. with octagonal barrel weighs 8 lbs., 11 ozs. The round barrel measures 0.740" at the muzzle while the octagonal barrel is 0.830" across its flats. Rifling twist rates are 1:18" for the .41 Mag. and 1:20" for the .44 Mag., and magazine capacity is 10 rounds.

Open sights are made by Marble’s Gun Sights, a company that was founded in 1887. Dovetailed to the barrel, the semi-buckhorn-style rear sight is adjustable for elevation by way of a ladder and for windage by drifting it in its dovetail slot. A simple blade dovetailed to the barrel up front has a 0.095" gold bead.

Lever-Action

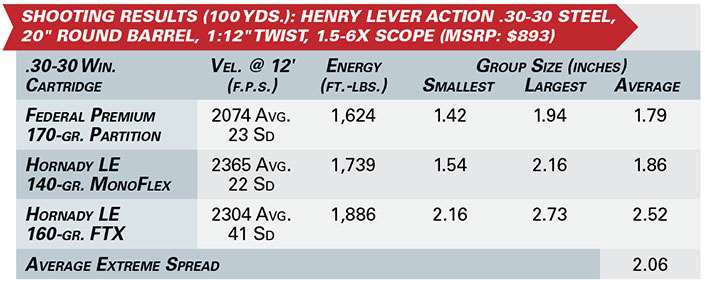

One might expect a rifle chambered for longer cartridges to be called Bigger Boy, but it is listed in the catalog as Lever Action .30-30 and Lever Action .45-70, introduced in 2008 and 2012, respectively. The receiver measures 6.75" long and 2" tall. Barrel lengths range from 18.43" to 22" and, again, overall weight depends on the type of barrel. The steel-frame .30-30 Win. with 20" round barrel weighs 7 lbs. compared to 8 lbs., 5 ozs., for the brass-frame rifle with octagonal barrel of the same length. The brass buttplate and barrel band on the latter also add a few ounces. Muzzle diameter of the round barrel is 0.655" while the octagonal barrel measures 0.830" across its flats.

I compared drop in the stock of the Henry .30-30 to that of my 1940s Winchester Model 94 in .32 Win. Spl. It was 2" at the combs of both rifles, but drop at heel was 2.5" for the Winchester and 3" for the Henry. When shouldered, one rifle felt as good as the other. Comb height of the Henry is low enough for use with its open sights and high enough for a firm cheek weld if a scope is attached with low rings.

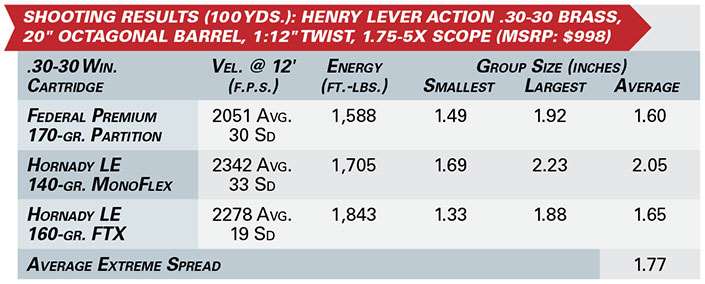

Curious to see what effect barrel weight might have on accuracy, I shot two rifles in .30-30 Win. with 20" round and octagonal barrels. The latter rifle proved to be more accurate with most loads, but accuracy of both was plenty good for bagging a buck as far away as most hunters take them with .30-30 rifles. Additional weight made the rifle with a curved brass buttplate about as comfortable to shoot as the lighter rifle with its rubber recoil pad. Magazine capacity of both is five rounds.

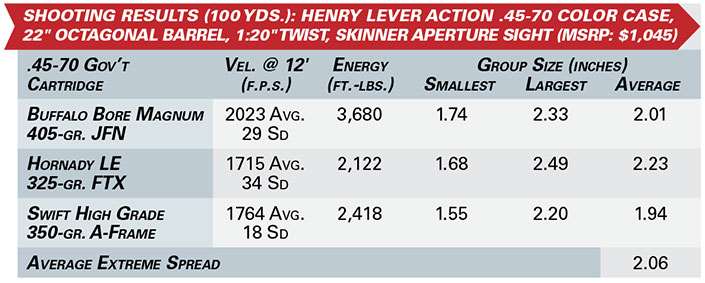

Moving up to the .45-70 Gov’t, Henry offers four lever-actions: a brass-receiver gun with a 22" octagonal barrel; a steel-receiver model with an 18.43" round barrel; a hard-chrome-plated All-Weather rifle with the shorter 18.43" round barrel; and a steel gun with a color-casehardened finish and a 22" octagonal barrel. The .45-70 I shot was an example of the latter, weighing exactly 8 lbs. with a magazine capacity of four rounds.

Feeding

In lieu of a loading gate in the side of the receiver, as seen on lever-action rifles made by Winchester and Marlin, center-fire rifles built by Henry are front-loaders. As previously described, the New Original Henry has a different front-load system while the others utilize the same tube-in-tube magazine design we are accustomed to seeing on rimfire rifles. A brass inner magazine containing a cartridge follower and its spring is enclosed by a steel tube. The tube is secured in place by a bracket dovetailed to the bottom of the barrel. Engaging a pin on the magazine of .22 rimfire rifles with a groove machined into the outer tube locks it in place. Due to the recoil of center-fire cartridges, the pin engages a groove in a heavier mounting bracket rather than in the outer tube.

Due to a few decades of hunting with Marlin and Winchester lever-actions, I tried my best to dislike the front-loading feature of Henry rifles. But while trying it, more positives than negatives were discovered. I found loading the magazine to be much easier, with not a single broken thumbnail. It is also equally friendly to both right- and left-handed shooters. Another plus is that the magazine can be emptied without cycling cartridges through the action. (It can also be done with other tube-magazine lever-actions, but not as easily.)

As mentioned earlier for the .22 Golden Boy, when unloading the magazine a hand is necessarily in close proximity to the muzzle. So, prior to moving up front, the chamber should be emptied and the lever left open. Then completely remove the inner magazine tube. Tilt the muzzle downward, and cartridges will slide out the “muzzle” of the outer tube. But remember that with the lever open, a cartridge remains on the carrier of the action. Re-inserting the empty magazine, pointing the rifle in a safe direction and cycling the action several times will remove that cartridge and make doubly sure the rifle is safe and clear.

The magazine is loaded only after making sure the chamber is empty. Several fellow members of my gun club have Henrys chambered for various center-fire cartridges, and I have observed a couple of them loading a rifle by holding it muzzle up, placing cartridges through the loading port in the bottom of the magazine and allowing cartridges to free-fall down the tube. Seeing the primers of cartridges impact against those already in the magazine makes me very nervous. I recommend holding the rifle horizontally and upside down with its muzzle pointed in a safe direction, but tilted just enough to allow cartridges to slide slowly down the tube.

The inner brass tube does add a bit of weight (6 ozs. for the .30-30 and 7 ozs. for the .45-70), but that’s not a bad thing when shooting stout .45-70 Gov’t loads. A partially empty magazine is not as quickly and easily topped-off as a side-loading design. Shoot the rifle dry, and it is slower to reload, but if a deer remains unscathed after a magazine full of cartridges is fired, it is doubtful that any rifle can be reloaded fast enough to prevent dinner from escaping.

Size & Safety

Whereas the Big Boy action is a scaled-down version of the Marlin 336 action, the longer Henry action pretty much duplicates its size and shape. Both also have a two-piece firing pin. Closing the finger lever elevates a hefty locking bolt at the rear of the action, and as its top end engages a deep notch in the bottom of the round breech bolt, it pushes the rear, spring-loaded section of the firing pin into alignment with its front section. That prevents the rifle from firing before the breech bolt is fully locked up. The extractor and ejector are also the same as on the Marlin. Whereas the carrier of the Winchester elevates a cartridge when the finger lever is pushed forward, the Marlin and Henry rifles do so as the lever is closed. Hunters have long debated which of the two is better, but I consider one as good as the other.

The passive safety system design of the .30-30, .45-70 and the Big Boy rifles appears to be simple enough, but to make sure I was on the right track I discussed it with Peter Etlicher who is the senior design engineer at Henry Repeating Arms. To begin, the hammer does not have a half-cock position. With the hammer cocked, pulling the trigger cams a steel transfer bar upward into a vertical slot in the face of the hammer. As the hammer speeds forward, the bar remains in position to transfer the blow from the hammer to the firing pin as long as the trigger is held back. If the trigger is released just as the hammer is manually moved forward, the transfer bar drops to its lowered position and the hammer is unable to make contact with the firing pin. If the trigger is held back while the hammer is being carefully lowered to its full-forward position, the transfer bar remains in its elevated position and will contact the firing pin. But since the firing pin is inertia-driven, it should not be long enough to make contact with the primer of a chambered round. Releasing the trigger at this point allows the transfer bar to drop to its safe position. In addition, a trigger block prevents the trigger from being pulled until the finger lever is completely closed.

Range Time

Not a single malfunction was experienced during my shooting tests. Wood-to-metal fit of all Henry rifles is uncommonly close, and overall finish is as good as it gets in mass-produced firearms. The stocks and fore-ends of steel-frame rifles have 16-line-per-inch cut checkering, and it is perfectly executed with no border run-overs or diamonds left begging to be pointed up. As lever-actions go, trigger quality is quite good. Average pull weights of the rifles you see in this report were 3 lbs., 13 ozs., for the .22 and 5 lbs., 12 ozs., for the center-fires. Cycle the New Original Henry and the Golden Boy actions, and you will swear their bolts are on greased roller bearings. The Big Boy and its long-action mates in .30-30 Win. and .45-70 Gov’t are not far behind them in smoothness.

The fact that the 535 employees at Henry Repeating Arms take great pride in their work is evident by the superb overall quality of rifles produced by their talented hands.