World War I was the first time in history where all sides applied science, innovation, inventions and mechanization to the battlefield to get the upper hand. One of the forgotten stories of the Great War is that of Jan Olieslagers, a well-known figure in aviation and racing at the turn of the century.

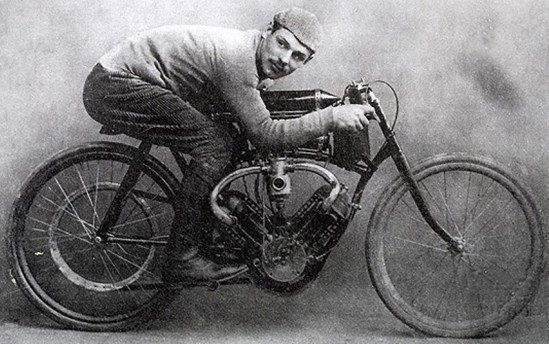

At the age of 14, Olieslagers was captivated by speed. Growing up in Belgium in the 1890s, he had the opportunity to work for a bicycle manufacturer, and he repaired racing bicycles at a local velodrome. As bicycles became motorized, the invention of the motorcycle intrigued him, so Olieslagers took a position with a motorcycle manufacturer. He started racing—and winning. By 1906, he was competing throughout Europe, specifically in Paris, France. Olieslagers’ prowess on the racetrack quickly earned him the nickname “The Devil of Antwerp,” referring to his hometown in Belgium. He often broke speed records and was recognized several times as the world speed champion, holding the world speed record between 1903 and 1908. Throughout this period, he was also involved in competitive pistol shooting.

Jan Olieslagers on a racing motorcycle, shortly after the turn of the century. The bike is reported to be a Minerva.

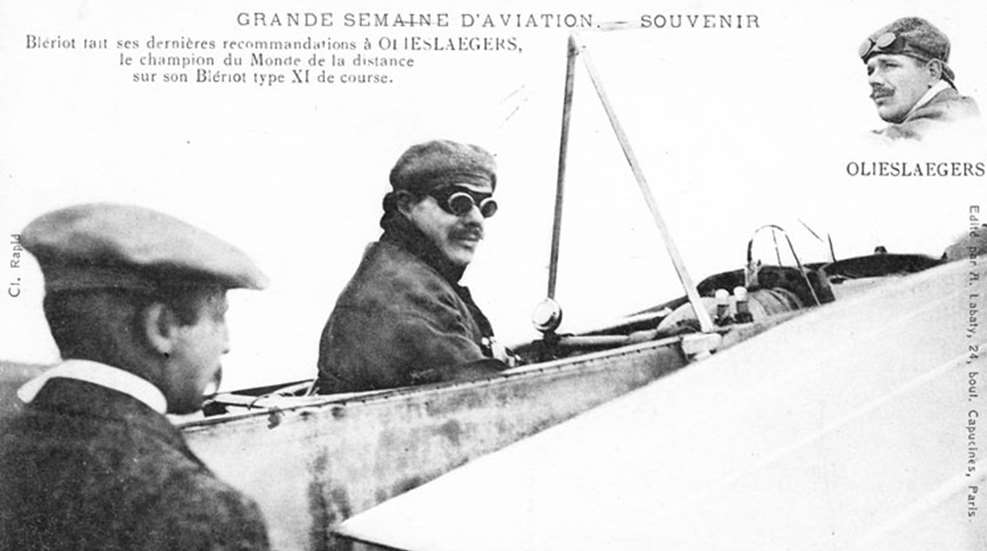

Simultaneously, the French press touted the exploits of aviation pioneers like Alberto Santos-Dumont, Henri Farman, Louis Blériot, Gabriel Voisin, and others. Olieslagers, fascinated by these aviators, set out to meet them. A bit shy, he was overwhelmed by the kindness of the Brazilian Santos-Dumont. A life-changing experience, Olieslagers decided to become a pilot.

Olieslagers met French aviator and airplane builder Louis Blériot, resulting in Olieslagers’ desire to purchase Blériot’s new Type XI monoplane. But Blériot was popular and could not produce the planes fast enough, so he offered Olieslagers his personal plane that he had crashed in Germany. Blériot would refurbish the plane and Olieslagers, an excellent mechanic, would work on the engine. The deal was struck, and in 1909 Olieslagers paid Blériot an astronomical price of 12,500 French francs.

Olieslagers never got any formal flight training, so he questioned Blériot’s chief mechanic, who offered some rudimentary tips on how to operate the flying machine. His maiden flight started well, but his landing was too hard, breaking the landing gear and damaging a wing. Blériot’s mechanic was present and reassured him that the damage was minor. Blériot himself visited to see the damage and congratulated Olieslagers on his flight. Olieslagers learned from his mistake and he returned home with his new plane, becoming the first man to fly in Antwerp, Belgium. Within a few months, he successfully learned to master his flying machine.

Jan Olieslagers with his first Blériot Model XI plane in 1909.

During this time, he met several businessmen who were interested in exploring natural resources in Algeria. Olieslagers was contracted to do geographical surveys from the air. He departed for the port city of Oran, Algeria, in November 1909 with his brother, Max, his mechanic and his plane. The expedition was well organized; one of the first tasks was to locate a suitable area for a landing strip. A location was promptly selected, and he supervised 200 workers in grading a 500-meter-long landing strip. Unbeknownst to Olieslagers, he was the first to create an airport on the African continent. The local population was terrified by the plane, but this quickly turned to curiosity and exhilaration. As a result, crowd control became problematic every time he landed.

In Algeria, Olieslagers tried aerial acrobatics for the first time. His attempt to do a figure eight turned into disaster when the plane snagged a telegraph wire. He crashed and the plane caught fire. Olieslagers escaped with burns, and lost his eyebrows and signature moustache. The engine was salvaged and the rest of the plane was abandoned. The press was quick to cover Olieslager’s exploits, including his accident. A fundraiser was promptly organized in Algeria; Olieslagers had gained celebrity status.

Olieslagers immediately placed an order with Blériot for a new plane. In the meantime, he was invited by the Spanish government to receive an order of planes for the government. They ordered him to fly to Seville for the first aerial meet in Spain. He did not miss the opportunity and won the first Coupe of Seville. Spectators were thrilled, and his fame and wealth grew exponentially.

Aerial meetings were being organized throughout Europe, and the demand exceeded Olieslagers’ abilities to transport his plane from one location to another, so he ordered a second plane with Blériot in 1910. His winning streak throughout Europe continued, often winning large purses offered by organizers. These prizes were generally linked to world speed and distance records.

Competition was fierce and, within the year, Olieslagers’ ordered a third Blériot plane; the latest and fastest model. By then, Olieslagers and Blériot were inseparable.

Olieslagers ventured into manufacturing in 1912 with both his brothers. The trio started building a plane based on a Blériot design. A rousing success, Olieslagers offered the plane as a gift to the Belgian military. To his surprise they turned him down as the monoplane was viewed as inferior to biplanes. Olieslagers anticipated war when the German ultimatum was announced in 1914.

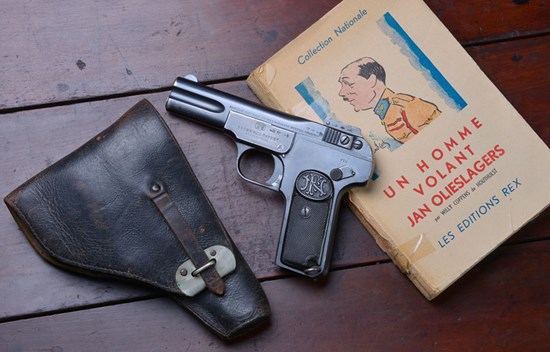

He telegraphed the Belgian Minister of War on August 1, and put himself, his planes, cars and staff at the disposal of the military. The minister replied and asked Olieslagers to report immediately. He was issued a new uniform and an FN Browning Model 1900 pistol. The only other pilot present at the barracks was his old friend and competitor, Jules Tyck. Both had been civilians, and they were now corporals in the Belgian Company of Aviators. Two days later, on Aug. 4, 1914, German forces invaded Belgium. Early that morning, Olieslagers was taken to the Belgian general staff. The commanding general asked if it was possible to drop a bomb from his plane on a German warship, which was making its way up the Scheldt River toward Antwerp. The notion of dropping bombs from a plane was radical and unconventional. Olieslagers confirmed that it was doable, but his plane was not nearby and needed to be transported first. This was done in record time, but arrived too late to complete the bombing run.

The Battle of Liège was raging, and Germans were moving into the countryside. In 1914, planes were not considered weapons, simply being thought of as observation vehicles. Pilots filled the traditional role of reconnaissance and observed troop movements. Encountering an enemy aircraft was unusual and, if it happened, airmen would exchange a wave or a salute. This was a gentleman’s code of conduct and, as many of the pilots were aristocrats, the code was strictly adhered to.

Such decorum was shattered on Aug. 10, 1914, when Olieslagers intercepted a German two-seater flying reconnaissance near the city of Leuven. The German crew spotted Olieslagers in his Blériot sport plane and, in traditional form, waved him a salutation. But the gesture had the opposite effect of what was intended, Olieslagers was offended and, in a moment of anger, drew his FN Browning 1900 pistol from his holster and fired at the Germans, emptying the magazine. The Germans, perplexed at what had happened, made a quick get away.

This seemingly small act would lead to the birth of aerial combat. There had been armed skirmishes between pilots before the war, yet none had led to any consequences. Olieslagers filed his report, and the word of armed conflict between pilots spread. Olieslagers was well aware that his first armed encounter had little more than a psychological effect.

Within days, Olieslagers became an instructor and flew two-seaters, while his brother flew the Blériot. The Belgian pilots were now taking FN Browning Pistols up in the air with bags of spare magazines. Some now mounted pistols to the inside of the cockpit to be more accessible. Word of aerial shootings spread quickly to the Allies.

Enemy planes were spotted more easily during the Battle of the Yser. Olieslagers met up with Allies and discussed air combat with a British officer, who gave him a handy carbine. A French NCO named Raffalovitch, an expert marksman, proposed to fly with him and try out the carbine. As a result, both men become committed to engage the enemy in the air. But Olieslagers’ commanding officer got wind of their plans and issued a direct order not to engage the enemy with arms or take part in any form of acrobatics. Olieslagers clashed with his commander, who was tiring of his fame and unconventional ways.

Despite disapproval from some officers, on Nov. 27, 1914, King Albert I awarded Jan Olieslagers the Order of Léopold, the country’s highest distinction. This further fueled conflict and renewed jealousy from superior officers who had denied him any promotion.

Olieslagers finally found an opportunity to get away from his jealous commander and joined a new squadron made up entirely of Blériot planes, including the plane he offered to the military in 1912. The 5thSquadron had only five pilots, and Olieslagers spent his days doing reconnaissance and transporting officers, dignitaries and training pilots. Olieslagers remained frustrated that he was not engaged in combat but he was finally recognized by his new commanding officer, and was himself promoted to officer.

Shortly afterwards, King Albert summoned him to his beach cottage at La Panne (the royal residence during the war) and decorated him again. King Albert, known as the King Soldier, was all too familiar with breaking protocols, and recognized Olieslagers as a true pioneer.

In March 1915, Olieslagers and his spotter reported that the Germans built a new bridge over flooded grounds, but another spotter contradicted Olieslagers’ report. Eager to prove his findings, Olieslagers took to the air with a 9”x12” sheet film camera and photographed the bridge. It marks the first time that photographic reconnaissance was used in the Belgian air force.

Despite his common-sense innovations, Olieslagers remained troubled by his lack of combat, as airmen were now downing German planes. The French pilot Roland Garros was the first to mount a machine gun on his plane. The gun was fired through the propeller. There was no timing device, so the propeller was reinforced with steel plates to deflect the bullets. Garros downed his first enemy plane with machine gun fire in March 1915 near the Belgian lines. Olieslagers eagerly inspected Garros’ machinegun setup. In contrast, the Belgian Blériot planes were still equipped with FN Browning 1900 pistols and various (sporting) carbines.

The summer of 1915 brought changes to the command and policies of the Belgian air force. Olieslagers was given a new Nieuport biplane, and the role of the spotter was now changed to spotter and machine gunner. The machine gun was mounted on a circular rail. Olieslagers disliked this configuration—the heavy machine gun impacted the balance of the plane and its size had a tendency to mess up aerodynamics: it made the plane brake depending on how the machine gun faced the wind and airflow.

Olieslagers’ new machine gunner lacked the drive for early sorties and combat, so Olieslagers took the matter in his own hands and started flying solo. He modified the mount to where the machine gun was static to his right. He could then operate the gun with his right hand, while flying the plane with his left. This was still not as efficient as Roland Garros’ setup, but Olieslagers worked with the tools that were available to him. He made numerous sorties each day and, between flights, spent his time in the hangar ready to intercept enemy planes.

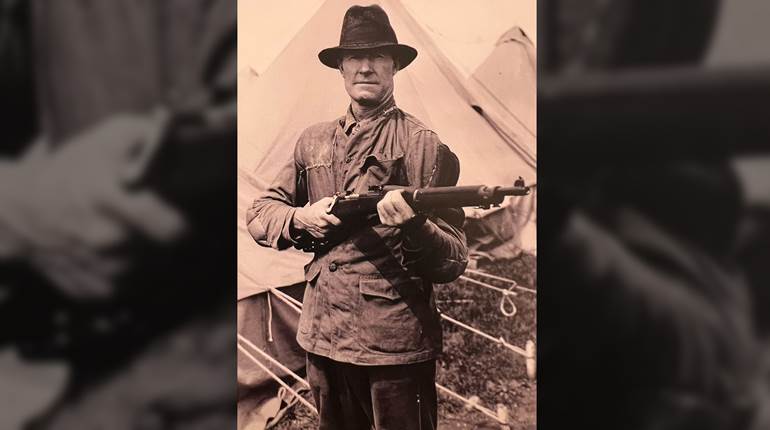

Olieslagers lobbied for a better plane—he desired a single-seater and communicated with the Nieuport factory in Issy-les-Moulineaux, France, which ended up converting his own plane to his specifications. The machine gun mount was improved, and Olieslagers was given a Lewis Gun as a special gift. He immediately set out to modify the gun—the barrel shroud, which added weight and interfered with aerodynamics, was removed and he focused on other weight saving alterations. Olieslagers discovered that the gun jammed under certain wind conditions and found a remedy. His alterations and improvements were communicated to BSA, which adopted them for their new aircraft model. Olieslagers’ recommendation that the magazine capacity be enlarged was also accepted.

Olieslagers lobbied for a better plane—he desired a single-seater and communicated with the Nieuport factory in Issy-les-Moulineaux, France, which ended up converting his own plane to his specifications. The machine gun mount was improved, and Olieslagers was given a Lewis Gun as a special gift. He immediately set out to modify the gun—the barrel shroud, which added weight and interfered with aerodynamics, was removed and he focused on other weight saving alterations. Olieslagers discovered that the gun jammed under certain wind conditions and found a remedy. His alterations and improvements were communicated to BSA, which adopted them for their new aircraft model. Olieslagers’ recommendation that the magazine capacity be enlarged was also accepted.

These changes were major improvements, but Olieslagers was not satisfied and conceptualized twin guns mounted above the radius of the propeller, in line with the axis of the plane, giving it better balance. The guns were activated by a cable, and Olieslagers designed a pivoting mount so the pilot could reach the guns to change magazines. Olieslagers’ designs and improvements were accepted by Nieuport, and the British Royal Flying Corps adopted his system. Olieslagers entertained British officers and provided them with technical information packets, including photographs and drawings of his innovations which he conceptualized with his brother Jules, who did the casting and machining of parts.

Finally, on Sept. 6, 1915, Jan Olieslagers engaged two enemy planes with his machine gun configuration—it was Olieslagers’ first true dogfight. Olieslagers enthusiastically flew sorties with a fierce determination, carrying at least five replacement magazines. He had made his fame long before the war started, so unlike many young aces, he was not concerned with official kills. It is not clear how many planes he downed as he most often flew solo. Although there were witnesses on the ground, the events were not officially recognized. As a result, Olieslagers was only credited with six kills. He engaged more than 100 planes in combat, and unofficial reports indicate that he downed more than 28 planes.

While younger pilots competed for kills, Jan Olieslagers was seen by many as a mentor and not a competitor. The history of Jan Olieslagers was actually put on paper in 1935 by Belgium’s top ace, Willy Coppens. Thanks to the efforts of Willy Coppens, the story of Olieslagers has not entirely been forgotten. Willy Coppens personally referred to Olieslagers as “Jean Sans Peur” (“Jan Without Fear”).

A Belgian military FN Browning 1900 pistol with officer's holster as would have been issued to Jan Olieslagers in 1914. Shown with a copy of Willy Coppens 1935 biographical book.

Olieslagers’ role as an armament and combat advisor cannot be underestimated. It is not clear exactly when Olieslagers went to England for the first time to consult on the Lewis Gun, though it is known that he met Col. Lewis in London on Jan. 6, 1916, and that both visited BSA to review and discuss his innovations. There are also reports that Olieslagers visited Vickers to consult on the Vickers Aircraft Gun. Olieslagers influenced arms designs and airplane evolution during the war as he communicated with several manufacturers, including Nieuport and Hanriot.

At the time of the armistice, Nov. 11, 1918, 35-year old Jan Olieslagers celebrated the end of the war as a lieutenant. He left the Belgian Air Force in 1919. While so many details of his work throughout the war have been lost, his decorations illustrate how he was revered:

Belgium: Order of Leopold (highest Belgian order), Belgian War Cross

France: Legion of Honor (highest French order of merit), French War Cross

Imperial Russia: Order of Saint-Stanislas

Serbia: Gold Medal for Bravery

King Albert I publicly promoted Olieslagers in 1919 to captain, but the old jealousies from commissioned officers resurfaced, and it would take six years for the Belgian War Department to recognize his promotion.

King Albert I died in 1934, and Olieslagers walked in the procession with the war veterans, holding the flag of the fraternity of war airmen. It was Olieslagers last public appearance. Jan Olieslagers died in Berchem, a suburb of Antwerp, on March 23, 1942. As he was living under German occupation, the details of his death are not known.

Today, a statue of Jan Olieslagers stands at the entrance of the Antwerp airport, which he helped establish after the war. There are many streets and avenues named after Jan Olieslagers, not only in Belgium but in The Netherlands as well. Sadly his story has not been taught for decades, and most people are not familiar with this talented pioneer.

Veteran’s Day, Nov. 11, 2018, is a day of remembrance like no other in our lifetime. It marks the 100thanniversary of Armistice Day: the end of World War I. Despite the historical importance and millions of casualties, we have seen little about the war in mainstream media. The event was only 100 years ago, the mere span of a lifetime, and yet so much history has already been lost or forgotten. It is a day we should remember not only all those who served in the U.S. military, but also aviation and air combat pioneer, Jan Olieslagers, alongside all others who fought and died in the war to end all wars.