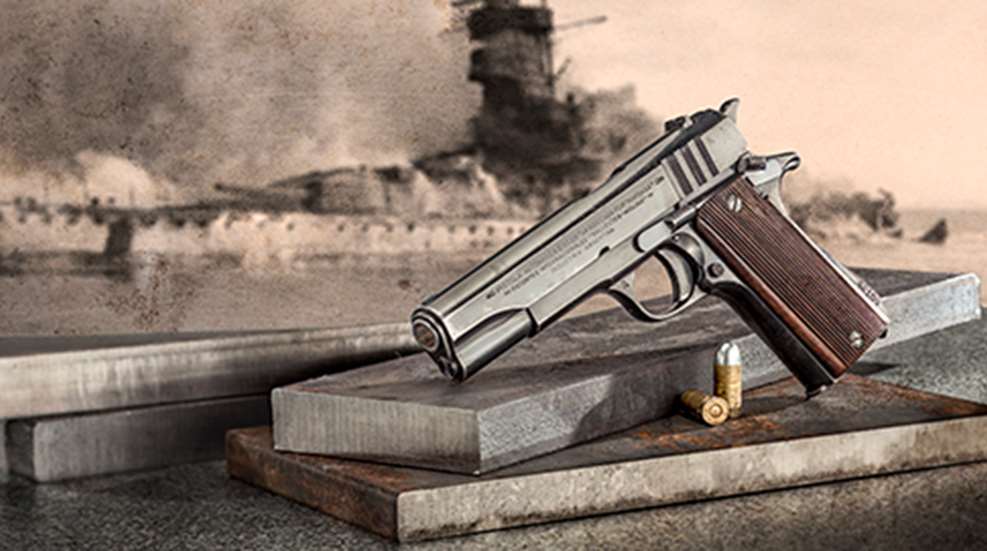

Legend has it that the steel in Argentine Ballester-Molina pistols came from the armor plate of the German “pocket battleship” Admiral Graf Spee. Is it fact or fantasy? Either way, it’s a great yarn. The legend has its origins in a true tale of British espionage in World War II. At its center are a famous Nazi warship, a long-ignored Argentine semi-automatic .45 ACP pistol, and cloak-and-dagger exploits that remain classified 75 years later.

I first heard the legend many years ago from the late Samuel Cummings, arguably the best-known international arms merchant since Sir Basil Zaharoff. The founder of Interarms, Cummings’ credentials included being the first to buy surplus arms from Argentina. Significant among his Argentine associates were members of the Ballester family. Unfortunately his penchant for storytelling sometimes blended fact and fable, and his credibility was not unassailable.

Introduced at the outset of World War II, the Ballester-Molina pistol had a proud career with the Argentine armed forces and police for nearly five decades. Through the years, numerous lots were imported into the United States and sold on the surplus market at low prices that belied the pistol’s exceptional quality.

The Ballester bore a close enough resemblance to the Colt Model 1911 to invite comparison that was both a blessing and a curse. In the United States, where the M1911 is revered with near-religious fervor, the Ballester is often disparaged as a poor imitation, an “unlicensed copy.” Yet its design and workmanship are worthy of closer scrutiny.

The legend begins on December 13, 1939, when the Graf Spee fought the first major sea battle of World War II. Designed as a powerful merchant raider, she was the size of a heavy cruiser but far more heavily armed, with six 11-inch guns in two triple turrets. Lean and sleek as a wolf, the Graf Spee was an engineering showpiece of the Nazi regime, one of the first major warships to have an all-welded hull, and diesel engines for phenomenally long cruising range. Already at sea when war broke out, the Graf Spee sank nine merchant ships before she was intercepted off the coast of Brazil by a force of British and New Zealand cruisers.

The Graf Spee fought them off with devastatingly accurate gunfire, then fled to the harbor of Montevideo, Uruguay, at the mouth of the River Plate. It was a refuge from which there would be no escape. Four days later, the Graf Spee sailed ominously out of the harbor toward her antagonists as thousands of spectators gathered on Montevideo’s waterfront promenades to watch the renewed battle. Just outside the three-mile limit the ship suddenly stopped, then thunderously exploded and burned, sinking to the muddy bottom of the estuary. Her captain, believing his situation hopeless, had scuttled her by detonating her torpedo warheads. But the water was only four fathoms deep, so her superstructure remained above the surface.

Film footage of the blazing hulk was swiftly distributed worldwide. The news was electrifying: the “Phony War” of stagnant armies and “bombing with leaflets” was over. The Battle of the River Plate was Britain’s first major victory against Hitler.

On the opposite shore of the Plate, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, the Ballester family owned a company called HAFDASA (Hispano-Argentino Fabrica de Automoviles, S.A.), that built truck engines. They also had developed a .45-cal. semi-automatic pistol that they hoped to sell to the Argentine military. Argentina had adopted the Colt M1911 and M1911A1 as the Modelos 1916 and 1927, and wanted to buy more. But Colt’s was by then fully occupied with war orders; none were obtainable from Hartford. There was a further obstacle: Argentina then had no significant steel industry and relied on imported steel. Its supply from the Krupp mills had been cut off by Britain’s naval blockade of Germany.

In a roundabout way the destruction of the Graf Spee may have solved everyone’s problems. The facts are fragmentary, inconclusive and shrouded in governmental secrecy, but this much is known: HAFDASA unexpectedly received a commercial order for a large quantity of pistols for export. When the Ballesters lamented the absence of steel to fulfill such an order, they reportedly were informed that more than 12,000 tons of the finest Kruppstahl lay available in the shallows of the River Plate estuary.

It turned out that the German embassy in Montevideo had been approached by an Uruguayan salvage company offering to buy the wreck of the Graf Spee for scrap. Believing the ship utterly destroyed, the Germans sold it for the equivalent of £14,000-in those days about $67,000. This was not altogether what it seemed. Not until 1977 was it finally revealed that the Uruguayan firm was a dummy: a front for MI6, the British secret intelligence service.

Photographs of the Graf Spee’s wreckage had been carefully studied in London by British electronics experts. They were fascinated by her antennae array, still intact. Some chauvinists in the Admiralty attributed the Graf Spee’s phenomenal gunnery to luck, but the experts knew better: The antennae supported a radar fire-control system the Germans called Seetakt. Radar was in its infancy in those days, and an inside look at German electronic technology was priceless.

Royal Navy electronics and salvage experts disguised with false passports and civilian clothes were rapidly dispatched to Montevideo. They spent two weeks on the wreck, dissecting the Graf Spee’s radar system (much to the outrage of German embassy officials who circled their former property in a hired yacht, watching helplessly through binoculars). But that’s another story, which Her Majesty’s secret service-true to tradition-still refuses to discuss.

After the Graf Spee had given up her precious mysteries, others began stripping off her steel. Her armor belt was 4-inches thick, and up to 3 inches on her decks. It is rumored-though unconfirmed-that some was cut into billets to supply HAFDASA. What is certain is that the factory somehow received enough steel to produce thousands of pistols, and that the steel was indeed of exceptionally fine quality. And who was the “export” customer for the pistols? Hardly shocking: the British government.

Many do not believe the steel came from the Graf Spee, but few dispute that it had to be of foreign origin. The fact that the British were able to get any pistols from Argentina is the most convincing evidence that they supplied-and controlled-the steel. Though officially neutral, the Argentine government sympathized with Germany. Indeed, the U.S. government imposed a munitions embargo on Argentina until 1947. Ordinarily Argentina would not have permitted HAFSDA to export pistols to England, particularly since its military wanted every one produced. Probably the British got delivery for two reasons. First, MI6 likely kept a tight fist on the steel supply, and Argentina was forced to accept a quid pro quo to get a share of it. Second, official resistance would have been softened by a deft application of fiscal lubricant (still politely referred to in Argentina as “oxygen”).

With their clandestine background, it is unsurprising that the British guns were not general-military-issue. Most went to the then-secret SOE (Special Operations Executive) the British counterpart to the American OSS. It is uncertain how many Ballesters the British received, perhaps 8,000 to 10,000. Practically nothing was recorded of their issue and use by SOE. In Churchill’s words, SOE was “to set Europe ablaze,” fomenting subversion and sabotage in Nazi-occupied countries; the details were secret. At war’s end some Ballesters remained in U.K. store-many unissued. Eventually Interarms bought them; most British-contract examples seen today came from that sale.

All Ballesters have the manufacturer’s serial number stamped vertically on the left side of the grip frame. Slides, barrels and magazines normally were numbered to match. Many have a secondary issue or contract number on the right side of the frame below the ejection port. British-contract guns can be distinguished by a “B.” prefix to this secondary number.

Typical examples I have recorded are serial number 17283, bearing secondary number B.4395, and serial number 18489, bearing secondary number B.5304. Other British-contract pistols have been reported as high as the 21000 serial number range, with secondary numbers up to B.8000. Argentine-issue guns are found with serial numbers scattered throughout that range, suggesting concurrent production for both customers.

The Ballester is not a Colt clone. It combines the best features of the Colt and the Spanish Star. Its lower half closely follows the Star Model P, with a pivoted trigger that usually renders a finer pull than a typical military M1911, and a hammer-locking safety (unlike the Colt, which locks only the sear). The gracefully curved backstrap is solid, without grip safety or separate hammer spring housing. Its rear tang is pronounced, affording good protection against “hammer bite”-no need for the now-fashionable beavertail.

The upper, however, is pure Colt, reversing the annoying changes introduced by Star for economical manufacture. Like the Colt-but unlike the Star-the Ballester’s firing pin and extractor can be readily disassembled without tools. Given the corrosive ammunition of that era and Star’s notoriously fragile firing pins, the inability to easily clean or replace them was a shortcoming that HAFDASA wisely avoided.

Also unlike Star, HAFDASA retained the Colt’s inertia-type firing pin, allowing the hammer to be safely lowered on a loaded chamber. Though a few parts-the magazine, barrel and recoil spring groups-will fit the Colt, the Ballester’s slide is about 0.250 inches shorter from the breech face rearward and will not interchange.

But what really makes the Ballester a standout are its materials and workmanship. Whether Graf Spee steel or not, it is of the finest quality, heat-treated in critical areas by electrical induction hardening, and finished to Colt pre-war commercial standards. The action is smooth as a wet ice cube, opening and closing with the clear tone of a bell. Even neglected, brown-dog examples sing when the slide is worked-proof that quality endures.

But was it the Graf Spee’s armor? Probing deeper, I consulted metallurgical studies of German armor plate commissioned during World War II by the U.S. National Defense Research Committee. Even before the war the Germans had tried to conserve nickel, which they chronically lacked, by using alloys correspondingly richer in chrome. To obtain properties necessary for face-hardening, their armor plate also contained vanadium in percentages described as “lavish.”

The studies found that German tank armor typically was composed of 1.45 percent chrome, 0.50 percent carbon, 0.60 percent molybdenum, 0.65 percent manganese, 0.25 percent silicon and-most significantly-0.20 percent or more vanadium. Nickel was present only in traces. Found in a pistol, this unusual alloy would be conspicuous as former German armor plate.

For this article a Ballester slide, serial number 19924, well within the British-contract range, was sacrificed for chemical and spectrographic analysis. The results were both disappointing and perplexing. The slide turned out to be high-manganese low-carbon steel having 1.07 percent manganese, 0.33 percent carbon and 0.19 percent silicon, roughly corresponding to SAE1033. It contained virtually no chrome, nickel or vanadium. So much for the Armor Plate Theory ... .

While the metallurgical analysis does not show that the steel came from the Graf Spee, it also does not show that it didn’t. A warship contains large quantities of many different types of steel besides armor plate. Steel with high manganese content is not an ideal choice for gun manufacture because it is tough to machine. This suggests that HAFDASA was forced to improvise with raw material salvaged from something, but unless and until more evidence comes to light, its source remains a mystery.

The pistols themselves are less mysterious. In the United States the Ballester’s torpid popularity is due, I suspect, to its slightly odd appearance. Its wooden stocks are vertically striated, the slide serrations are inexplicably sliced into three groups, and the trigger guard seems bent. The overall effect is not endearing. Evidently the designer tried to make it distinctive but succeeded only in making it appear strange.

But styling aside, the Ballester delivers impressive performance. For several years I shot one Navy-issue example extensively as a “control” in testing other .45-cal. pistols of new manufacture. The salient impression received from a Ballester is bank-vault solidarity. It feels heavier than a Colt (and it is); its slide-to-frame fit is superb, and the trigger is typically excellent. Functioning is consistently flawless. Inherent accuracy is remarkable for a service pistol-if one can see the pitiful pre-war sights.

About 1987 the German firm of Frankonia Jagdwaffen bought a small lot of the pistols and-in perhaps more than one sense-took the steel home. In accordance with German law the pistols were re-proofed. Exported later to the United States, their German proof stamps attracted the attention of collectors. Some fail to note that the eagles are of post-war vintage.

There are, however, numerous legitimate variations for collectors. Ballesters are found bearing the Argentine national crest and a slide inscription “Ejercito Argentino” (Army), or “Armada Argentina” (Navy). Those marked “Aeronautica Argentina” bear instead the winged crest of the Air Force. Examples roll-marked “Policia de la Capital” (Buenos Aires district police) also are observed, along with many other slide inscriptions denoting various police agencies. Some can be found marked Ballester-Rigaud, the latter a HAFDASA engineer responsible for the pistol’s early development.

The wreck of the Graf Spee is no longer visible on the surface. Scrap salvagers and astonishingly violent storms on the River Plate have leveled the superstructure, though many scuba divers still explore her hulk underwater and occasionally perish in the tangle. Efforts to remove the wreck as a hazard to navigation were finally abandoned. What is left has settled into the muddy bottom. As late as 1989 what appeared to be the tip of her mast could still be seen from shore, but that has disappeared, too. So has HAFDASA. It went out of business in 1953. By then about 100,000 Ballesters had been produced.

If the legend of the Graf Spee is true, her steel served reincarnate well into the 1980s. In September 1984 at the Argentine Navy’s Escuela de Mecanica in Buenos Aires, I waited interminably in a guard hut for permission to enter. On duty was a grizzled petty officer wearing a sidearm in a covered leather holster.

To make conversation the superannuated chief was asked which of the many different kinds of handguns in Argentine service he was carrying. With a bored shrug suggesting that the answer should be obvious, he lifted the holster flap, exposing a vertically-striated wooden stock.

Tapping it with his forefinger for emphasis, “The best,” he said.