Shooters tend to have a stable of well-worn mental conundrums that serve in equal parts as diversions, journeys of discovery, solutions to a problem or (and perhaps most often) excuses to acquire a new firearm. These usually follow either the face-off (as in the “this” vs. “that” debate) or the “best quest:” What is the best (insert item) for (insert utilization)? You can almost tell how long someone has been a gun guy by how many of these they have worked through with some degree of confidence.

One of these evergreen debates is the best “adventure” or “backwoods” sidearm, most often in the guise of some form of powerful caliber suitable for engaging a non-human apex predator, usually a bear. I jokingly refer to these firearms as “Bearosaurus” guns. And, of course, I too have passed some time on the range and in deep thought considering the pluses and minuses of various handgun types. I was recently reminded of this when a friend, a Marine colonel, was telling me about a backcountry bow-hunting trip he is planning in grizzly country. The colonel was clearly going through the same ritual debate, and it brought me back to some shooting I did while exploring this very topic.

I had first adapted a defensive drill to simulate a roaring, angry charge by some dangerous man eater using three targets in tight echelon: one each at 7, 5 and 3 yards. The “shoot to stop against sabertooth” scenario had the shooter start at the ready position and fire one shot to the 7-yard target, two shots at the 5 yarder, and three last ditch shots into the target placed 9 feet away for a total of six shots to three 8" vital zones. After running this a few times I dubbed the set up the “Bearosaurus Rex’ drill. The drill would give a meaningful comparison of different calibers/action types in an approximation of a worst-case fight for who’s on top of the food chain.

I ran the Bearosaurus Rex with examples of three common backcountry guns: a large-caliber single-action revolver, big-bore double-action wheelie, and a 10 mm semi-automatic. I rounded up a 5.5” Ruger Bisley in .45 Colt, a nickel-plated Smith Model 57 4” .41 Mag., and a Glock 20. I would have preferred a .44 Magnum Model 29 since there are many more .44 Mags. in the wild than .41 Mags., but the 57 was all I had at the time. As a plus, the .41 Mag. is a more direct comparison to the 10 mm Auto.

Then Ruger launched heavy “Ruger only” handloads, pushing a 300-gr. Hornady XTP at just under 1100 f.p.s., not the heaviest loads possible but still magnum class. I ran the 57 with loads that represent two different levels of recoil—the Winchester Silvertip 175 gr. JHPs and 21- gr. Federal Swifts. The Glock was pushing 180-gr. Federal Trophy Bonded soft points as well as MagTech FMJs.

One can note the absence of any of the “really big” big-bores or magnums such as the .500 S&W or Linebaugh-type cartridges. I didn’t have access to any of those and didn’t put any effort into including them. For my needs, .44 Mag. or heavy .45 Colt is about the limit of what I can easily carry and readily control. A prospective adventurer can easily run this drill with an X frame Smith or a custom five-shot boomer to see how they fare, scaling it to five shots by removing the third shot at 3 yards.

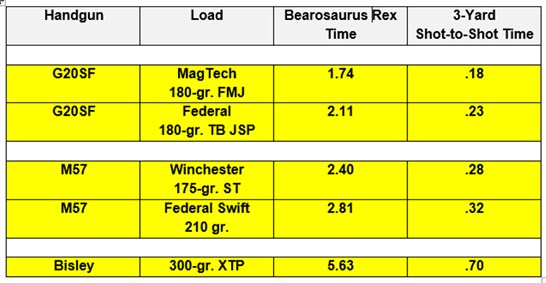

The chart shows the data but some context may be helpful. I am pretty confident with each of the action types, but have the least experience running a big-bore single action at speed, perhaps not unlike many who belt one on to wander afield into something scary’s feeding grounds. I fired my way through the drill a couple of times with each handgun type to capture what seemed to be about my predictable best-case performance minus a dose of specific, dedicated practice; I’m sure that each could be improved with effort. As a baseline I can run this drill with just about any service pistol chambered in 9 mm in about a second and a half and down to as little as 1.34 seconds with favored handguns like the Beretta Elite LTT or 1911. In 9 mm.

Outside of the raw numbers, I can tell you “hanging on” at the posted speeds was a tough job with most everything other than the .41 Mag. with the Silvertips and the Glock with the MagTech FMJs. Since the drill requires transitioning targets, follow-ups, and acceleration as the target is nearer, there is a lot going on when you are also dealing with heavy recoil. Of course, there is no real stress either; a charge by your neighbor’s feisty chihuahua is likely more stressful than running a static-shooting drill. If you are barely in control on the Bearosaurus Rex, then fending off Sasquatch is going to be a real chore.

Shooting the Bearosaurus Rex Drill is actually quite an exhilarating experience, kind of like riding a horse that is bucking enough to let you know its displeasure, but just under the line where you are definitely getting tossed from the saddle. The shooter, if running the Rex at top speed, is only just in control. There is a tremendous amount of blast and muzzle energy launching at your command in a very condensed time frame, and the experience is quite unlike simply firing a magnum.

More powerful loads look good on paper until you try to run them hard on a realistic drill. Once speed and accuracy are measured, compromise looks attractive. Alternatively, some shooters faced with poor control rationalize they will only need one or two shots. Maybe so … but maybe not.

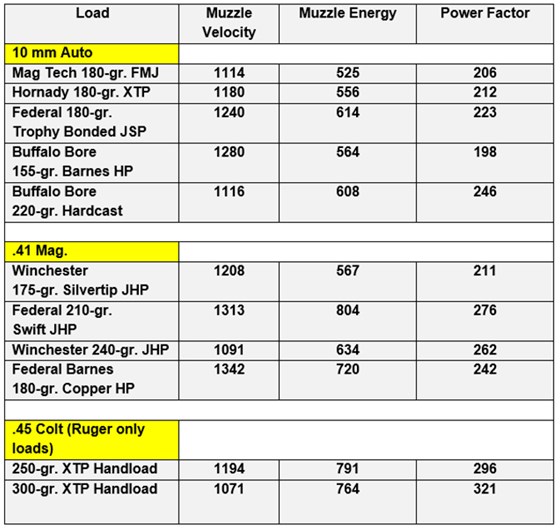

The loads are listed below, along with their velocity, muzzle energy and power factor. Power factor is probably a better proxy for recoil than muzzle energy, as it is simply bullet weight in grains multiplied by velocity in f.p.s. with the answer divided by 1000 to streamline the number. As a reference point many 9 mm Luger loads have about 130 power factor while .45 ACP 230- gr. hardball tends to be around 190. Different shooters have differing levels of tolerance, but for me, when power factor tops much past 200, I am struggling against recoil rather than managing it. The chart shows additional loads from those handguns I had chronographed data on for further reference.

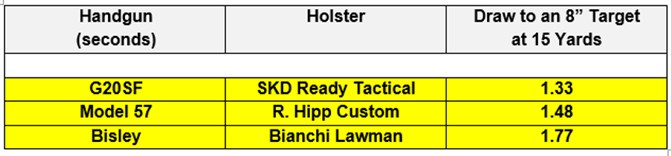

Some adventurers are more concerned with time into action than speed for multiple shots. I logged that as well with the Bearosaurus guns, drawing each from the holster and recording the time to a 15-yard hit to an eight=-inch steel plate—a demanding enough target/distance to require good application of technique. Draw speed is a pretty individual measure that may or may not have much transference, but my results are shown below.

Of course, the Bearosaurus Rex isn’t the final word on sidearm selection. These three examples have plenty of other trade-offs. I can hit best at distance with the Bisley, but it is also the heaviest. The Glock has the edge in both weight, weather resistance and capacity, but may be somewhat light against the biggest things trying to maul or eat you.

Shortly after I had completed shooting through the comparisons, I was talking with a buddy who lives on some property in the Midwest and happened to be going through an almost exactly parallel process for his hunting-season “ranch gun”. I found it interesting that at the time he was debating between somewhat similar choices; a 10 mm Wilson Combat 1911, a Smith & Wesson Model 24 (N frame double-action .44 Spl.), and a Ruger Bisley .44 Spl., both Specials with heavy loads. And, like I did, he was enjoying the deliberation but not convinced the data was the final word. Sometimes, passion and reason collide and a shooter simply wants to carry an old favorite or a sidearm that will do the job, while adding to the quality of the experience. Thus, the debate goes on.