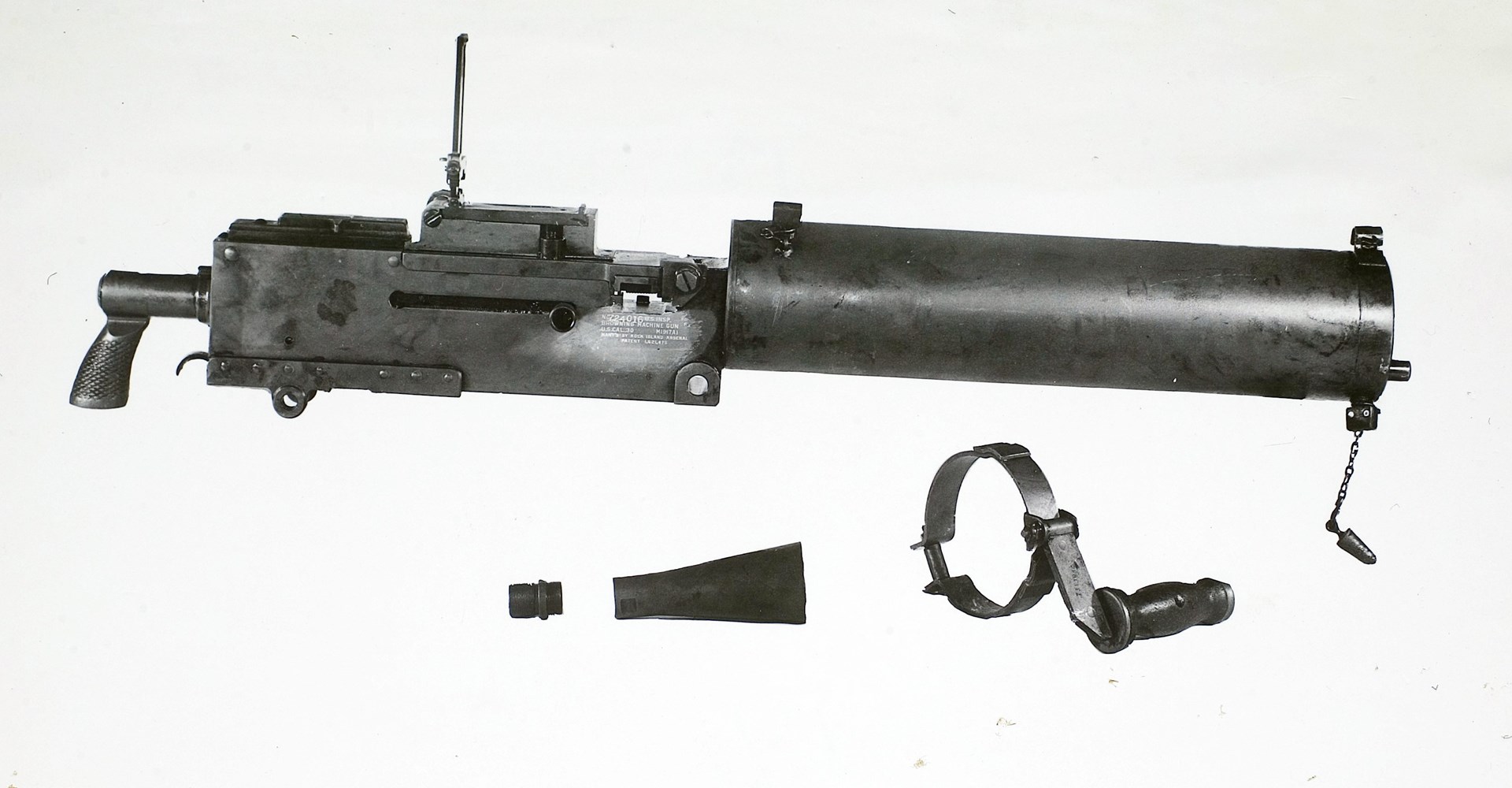

In this era, if you use the term “Heavy Browning,” many people will assume you are referring to the .50-cal. Browning M2 machine gun. While that is technically correct, Browning’s massive .50-cal. design is truly in a category of its own. Call it semantics, but in the first half of the 20th century, the term “Heavy Browning” referred to the .30 -cal. M1917 water-cooled machine gun.

In early 1918, there were two Browning machine gun designs being prepared for service: the Browning Automatic Rifle and the tripod-mounted M1917. While the nearly 20-pound M1918 BAR may have been heavy for a rifle, it was incredibly light for a machine gun at that time. Consequently, the BAR was soon described as the “Light Browning,” while the 47-pound M1917 machine gun (about 103 pounds total with tripod, a full water jacket and ammunition) became known as the “Heavy Browning.”

After World War I, the BAR was often known by its acronym alone, while the M1917 became the U.S. military’s heavy machine gun. During the early 1930s, the U.S. Army began to use the air-cooled .30-cal. Browning M1919 machine gun (31 pounds for the gun, and about 16 pounds for the M2 tripod). The new M1919 became the “Light Browning,” while the M1917 (and updated M1917A1) retained its heavyweight title. Through World War II, most U.S. military documentation refers to the M1917A1 as a “heavy machine gun.”

The Sustained Fire Conundrum

Compared with its water-cooled contemporaries from World War I, the M1917 machine gun was significantly lighter and more compact. U.S. Ordnance was very enthusiastic about the weapon, and the U.S. Army went from having no indigenous heavy machine gun to possessing one of the best in its class in a little more than a year. In an era with high expectations of sustained fire, the U.S. military found itself with a machine gun capable of firing 50,000 rounds without a stoppage.

Major E.P. Church’s 1918 report to the U.S. Ordnance Department noted that after the 80th Division Doughboys had transitioned to the new Browning M1917 during October 1918, their first barrage from 72 guns totaled 642,000 rounds with “the only trouble experienced was from an occasional ruptured cartridge, and with the slight difficulty in some cases with leaky jackets.” Major Church also stated that he believed the Browning machine guns “even increased the admirable morale the division already possessed.”

Sustained fire capabilities come at a cost, and in this case, that cost was paid in extra weight. Nothing taxes the infantryman more than the burden he carries on his back—the water for the cooling jacket adds pounds and another layer of complexity to manage. The tripod is sturdy and very stable, but it, too, is heavy. And then there is the ammunition, the water condensing can and the tool kit. To a modern machine gunner, the whole thing looks like an impractical nightmare—at least until you mention the incredible sustained fire capability, and the discussion starts all over again.

My father was a sergeant in a heavy weapons company of the 8th Infantry Division during World War II, and he was a big proponent of the M1917A1. He spent more than two years with that weapon, and it left an indelible impression of reliability on him—with water in the cooling jacket and ample ammunition “you could fire all week.” Some of its water-cooled attributes were hard to translate across the machine gun generations, particularly the old gunner’s art/science of indirect fire.

I had hoped to describe the practice here, but while I am strong in history, I am terrible at math. The base concept requires a water-cooled gun like the M1917A1, and plenty of ammunition. The result of this indirect machine gun fire saturates an area with .30-cal. slugs, keeping enemy heads down and covering infantry operations in a way not thought possible before—and with the retirement of water-cooled machine guns during the 1960s, this unique tactic isn’t really available anymore.

Writing about the Browning M1917A1 in his classic volume Shots fired in Anger (Small Arms Technical Publishing Company 1947), Lt. Colonel John B. George notes the U.S. Army’s infatuation with the strange magic of indirect machine gun fire between the world wars:

“It was an improved development of World War I, where it was discovered that machine guns could do more than merely spray an enemy attacking in front of their very muzzles. In mounting the gun solidly, it was learned that an even distribution of bullet strikes could be spread nicely over a fixed and predetermined area, making the old spray gun an excellent long-range weapon. It was also discovered that with fixed tripods and artillery type instruments (range finders, aiming circles) machine guns could be fired accurately at targets not in the view of the gunner—indirect fire.

Because it was so mystic, I guess, this indirect fire became the pet subject of every postwar machine gun instructor and, though it was an admittedly lesser role of the weapon, we began to find great emphasis being placed upon it. The changes in the heavy machine gun tripod after World War I tended toward improvements for such indirect fire, and ultra-long-range machine-gun fire was certainly the main consideration in the later design of the boat tail bullet replacing the flat base of the M-1918 ammunition. The new cartridge, designated the M1, was fitted for long-range machine-gun fire. Instructors began to speak of machine guns, with their new ability to reach 4000 yards, as competitors of artillery in flat terrain. Fortunately, this idea did not hold for long.”

There were a few unique accessories issued with the M1917 machine guns, including the “asbestos mitten.” This description comes from the M1917A1 handbook:

Asbestos Mittens: Asbestos mittens are issued for use with machine guns to facilitate the handling of the gun when hot, particularly when moving to a new position by hand, or when changing barrels.

My father described this as a critical piece of gear for the gunners, as it was necessary when handling a hot gun. It could also be used in an emergency to fire the M1917 from the hip. While the water cools the barrel sufficiently, the metal jacket still contains boiling water and could cause severe burns on the gunner. I remember one of dad’s comments on firing the heavy Browning without the tripod: “Bend your knees, start out low and let the gun walk itself up to the target. You’ll get the hang of it after a couple of bursts.” I was about 12 years old when he offered that advice, and I haven’t had the opportunity to try it yet. But a boy can always dream.

Late in WWII, a specific carrying handle was developed for the M1917A1—a solidly constructed hand grip that attached to the water jacket with a metal clamp. Another late addition to the M1917A1 accessories was something you don’t normally think of with an automatic weapon: antifreeze. The handbook describes the mixture:

Antifreeze: During cold weather, it is necessary to guard against freezing of the water in the water jacket. In locations where the atmospheric temperature is below 32 degrees F, an antifreeze compound is used in the water that does not freeze or gum and yet cools the barrel. It is satisfactory for temperatures as low as minus 60 F, when mixed with water in proper proportions.

I spoke with Capt. Dale Dye, USMC, to get his thoughts about the M1917A1. Even though the water-cooled machine gun was no longer in service when he joined the Marine Corps in 1964, he still had relevant and interesting experience with the gun. This came through his work on the HBO series “The Pacific:”

“It was heavy and prone to overheating during sustained fire if you didn’t keep the water jacket filled—but otherwise it ran like a Swiss watch. Sometimes the fabric ammo belts stretched out of shape or twisted during feeding. The rubber hose that connected the water tank to the barrel jacket was subject to damage or rotting in the jungle conditions. On the other hand, Korean War machine gunners told horror stories about frozen water jackets that prompted them to wrap the barrel in blankets.

I’ve heard stories from World War II vets about water jackets being penetrated by shrapnel—eliminating the gun from its primary purpose of sustained fire. There were also lots of tales of strange liquids used to refill the water jacket, ranging from fruit juice to the gunners pissing into them. It was difficult to confirm much of this, but the stories were entertaining to hear.”

The M1917 and M1917A1 would serve American troops from the Doughboys of World War I through the GIs of the Korean War and the beginning of the Atomic Age. When the “Heavy Browning” was finally retired, it had earned its place among the greatest infantry weapons in American military history. Few other U.S. military firearms have delivered such a sustained level of firepower as John Moses Browning’s genius invention.

I did some digging through dusty old files, lessons learned and after-action reports to give you an idea of how American troops used the M1917, in their own words.

In Battle Experiences Against the Japanese (published in May 1945), I found several references to the use of the M1917A1, along with some widely differing opinions on how the “Heavy Browning” should be employed.

Conflicting views on the use of heavy machine guns on offense

- "I recommend substituting the light machine gun for the heavy machine gun for offensive operations in the jungle. The heavy machine guns, however, are very valuable in the defense." Col, 5th Marine Regt.

- "It pays to use the heavy machine guns when attacking in the jungle. There is a difference of opinion on this matter. It is hard work, yes, but don't overlook their value, morale and otherwise, and don't forget their high rate of fire." Lt Col, 7th Marine Regt, Guadalcanal

Heavy machine guns against snipers

"We supported jungle attacks with our heavy machine guns, raising their fire to treetops 50 to 100 yards to the front at the moment attacking troops passed through the front line. We maintained this fire until ricocheting bullets endangered our own men. The fire caused many casualties among Japs in trees overlooking our position." 3rd Marine Regt, Bougainville.

Defense against Japanese attacks

"The Japanese always try to get machine guns out of action as early as possible. To do this they may deliberately expose small groups. Most of these Jap groups can be wiped out with mortars, rifles, carbines or grenades. That keeps the location of the machine guns concealed until the real attack is made and they can achieve mass slaughter. When repeated assaults are made, the Japanese would send men armed with knives and grenades forward to get the machine guns which had repelled the last assault. Late one night the enemy did succeed in putting out of action most machine guns in one sector. This was blamed on excessive firing, premature firing, and failure to move to alternate positions often enough."—Observer. Admiralty Islands.

MG positions at night

"To guard against attacks by Jap patrols after dark, we would set up the machine guns at one place and then immediately after dark move then to another prepared location. We would leave riflemen in a position where they could ambush the Japs when they tried to hit that original machine gun."--Lt Standridge, 43rd Inf Div, Southwest Pacific

“Battle Experiences ETO” (April 1945) provided information on this tripod adaptation (used in the ETO and PTO).

Heavy machine gun on light tripod

"Make sure that all men have fired the heavy machine gun using the slight machine gun tripod--we used it more often than the heavy tripod in the hedgerows."—Platoon Leader, 119th Infantry Regt, 30th Inf Div

“Battle Experiences in Normandy” (July 1944), contained this advice from frontline troops.

Spray for Snipers

"Heavy machine guns are used to spray taller trees likely to contain enemy snipers."--Platoon Leader, 83rd Div.

Comments from Heavy Weapons Platoon Commanders

Close supporting machine guns: In the attack we have used a section of heavy MGs in support of each assault company. Their mission is to protect the flanks of the battalion. When the attack succeeds, they may come up closer to cover the reorganization on the objective. When the attack is resumed, they drop back to carry out their flank security mission. If they get too close to the assault company, they cannot accomplish this and they draw mortar or arty fire on the assault troops. After reaching a final objective we like to draw the HMG sections into the center of the two forward companies and let the LMGs take the flanks.

Long range machine guns: The other platoon of HMGs should, if possible, follow the assault companies near or in front of the support company. They should be given the mission of long range and overhead fire. They must not fire unless they have a target; they must not use tracers; they must change position after a few bursts; they must put one section above the other when ground permits; the support company must protect them with a squad from the support platoon; the platoon leader must be given freedom of movement and decision by the company commander, especially as to displacing forward.

Machine guns for the support rifle company: If the support company is committed, we sometimes attach the long range and overhead platoon or at least a section of it to this company. If one section goes with the support company the remaining section can continue the long range or overhead mission or be shoved forward to the company delayed by the heaviest fire or support it by fire from where it is.

Machine guns in defense: When it has been necessary to defend, we have found it quite difficult to establish final protective lines because of the hilly terrain. We have placed MGs to protect the flanks and avenues of approach into our positions. A rear slope defense seems to be the most practical as extremely accurate arty fire makes a forward slope almost untenable.

Controlled fire: "Most machine gunners fire too long bursts. This results in excessive smoke, dust, and sometimes steam, thereby disclosing the gunner's position, such long bursts also result in wild firing unless followed by re-laying. The rate of fire should not be reduced, but bursts of not more than 5 rounds are more effective." CO 1st Battalion, 26th infantry, 1st Div.

Forget the hedgerows: “The quicker we can forget the hedgerow style of fighting and get back to the idea of using our heavy MGs in support, the better off we will be."--T/Sgt L.A. Coleman, Co H, 11th Inf Regt.

A Report From Korea

The M1917A1 machine gun fought on through the Korean War in the hands of the U.S. Army and the USMC. The need for the “heavy Browning” remained a constant, but the rugged terrain and extreme weather conditions limited its contributions. In S.L.A. Marshall’s Commentary on infantry operations and weapons usage in Korea, Winter 1950-51, it is apparent that the gunners’ perceptions of their techniques did not sync up with the reality on the Korean battlefield:

“According to the testimony of all troops, panic firing and excessive rates of fire among the machine guns are not in evidence. By their own statements, the gunners exercise restraint even under conditions of great pressure, such as surprise or the presence of a numerically superior enemy force in night attack. “I continued to fire in short bursts,” is the customary size-up by the gunner of his own action. This testimony must be received with some reservation. The interrogations indicate that in the mind of the average gunner “firing in short bursts” is about synonymous with lifting the finger from the trigger for a few seconds at frequent intervals rather than resting the gun when there are no manifest targets and no compelling tactical reasons for firing. This affords no relief to the weapon so far as over-heating is concerned, and it does not conserve ammunition.”

Marshall notes that it wasn’t the weapon or its capabilities that changed during the few years between WWII and Korea, but rather the mindset of the troops:

“A main lesson of the Korean war is that within the short space of five years even those officers and NCOs who had become skilled combat hands in World War II had been permitted to forget how things were done. By their own account, their knowledge and confidence had not been adequately refreshed, and they were again “green” when they entered battle.”

"A grand gun to stop a Banzai charge"

Wrapping up his thoughts on the M1917A1 in “Shots Fired in Anger”, Lt. Colonel George provides a fitting summary of Browning’s water-cooled death dealer:

“The gun did fine yeoman service as a defensive firepower weapon, either for fixed final protective fire or for spraying. In the earlier perimeter battles, for instance, it was the mainstay of a battalion line that held tight and killed more than 900 Japanese with negligible loss to themselves. Marines used the “Heavies” all along with good effect. For us, though, the Heavy was never more than a static defense weapon—a grand gun with which to stop a Banzai charge.”

An Interview With Marine Corps Sgt. John Basilone

John Basilone is probably the most famous of all Browning machine gunners, and his thoughts on the M1917A1 are golden nuggets of American firearm lore. On Sept. 1, 1943, Capt. Martin of USMC Public Relations spoke with Platoon Sgt. Basilone about his Medal of Honor actions on Guadalcanal on the night of Oct. 24-25, 1942. The following are excerpts from that interview:

Captain Martin: “I presume you had some interest in machine guns otherwise you wouldn’t have been with the weapons company.”

Sergeant Basilone: “All my time served in the Army was with the machine gun company. When I arrived in Quantico to report for duty, they immediately looked up my record and when they found out I was machine gunner, as they say in any of the services---once a machine gunner, always a machine gunner.

Captain Martin: Incidentally, they were the same type of machine guns in the Marine Corps that you had used in the Army.

Sergeant Basilone: Yes, they were the same type.

Captain Martin: I understand all the machine guns used in the Marine Corps are Army procured.

Sergeant Basilone: They are.

Captain Martin: Hopping back to the action on Guadalcanal the night of October 24 - 25, you say that you were on the left flank with two machine guns and a runner came over from the right flank and said that the guns over there were out?

Captain Martin: When you got to the right flank what was the situation there?

Sergeant Basilone: The situation there was already, the men who were killed were already brought behind the lines and the fellow that was wounded was still standing there. Another little chap named Evans was there. So, when we got there...

Captain Martin: There were just two of them left when you got there?

Sergeant Basilone: Just two.

Captain Martin: Were they both firing then?

Sergeant Basilone: Yes, they were.

Captain Martin: Rifles?

Sergeant Basilone: Rifles, pistols, whatever they had.

Captain Martin: But the machine guns were not in action?

Sergeant Basilone: No, the machine guns were not in action.

Captain Martin: And so, you planted the machine gun that you had carried over in your arms?

Sergeant Basilone: Right in the open.

Captain Martin: Right in the open. And did you get that in action right away?

Sergeant Basilone: Immediately.

Captain Martin: Then what happened?

Sergeant Basilone: Then after I fired a little bit, I rolled out of there, the gun was still loaded, the fellows were still firing. I rolled into the hole where the gun was busted and immediately fixed it.

Captain Martin: What was the matter with that gun?

Sergeant Basilone: It had a ruptured cartridge. That was all that was wrong. It was just the excitement that the fellow that was firing it was just a little excited.

Captain Martin: How long did it take you to repair it?

Sergeant Basilone: Oh, approximately, it took me about, less than a minute, I'd say.

Captain Martin: About a minute to repair it and then you got that in action too?

Sergeant Basilone: Yes, I did.

…….

Captain Martin: I understand you say you posted one guy on the right flank and one on the left flank and then you fired the two machine guns by rolling between them. How did you do that? How far apart were the machine guns?

Sergeant Basilone: They were very close together. There was only about two-foot distance between them. I fired one, and when I finished firing that one, I just rolled over to the other and fired it and immediately reloaded the two guns.

Captain Martin: What were you doing, firing the whole belt on one gun before you went to the other or were you firing them in bursts?

Sergeant Basilone: I was firing them in bursts sometimes. Sometimes I fired much larger bursts. It depends upon how many Japs were coming over.

Captain Martin: And how far away were the wires? Did I hear you say 30 feet in front of your machine gun emplacement? That was the second line of defense wires, wasn't it? Wasn't there an outer defense of wires?

Sergeant Basilone: Those were the only wires.

Captain Martin: Were most of the bodies inside the wire, that is between the wire and your machine gun emplacement...or were most of them on the other side of the wire?

Sergeant Basilone: From what the Colonel told us there were 900 on this side of the wire. On the other side there were about 2,000.

Captain Martin: About 2,000? And the reason I asked that question is, I wanted to know how far away you could see them?

Sergeant Basilone: We could see them in the moonlight during the night, we could see them crawling across, some crawling through the wires, some rushing the wires. We could see them, well anywhere, right to the wires, we could see them. Right behind the wires, it was rather jungle-like.

Captain Martin: Was that jungle country you were in? You were not up on a ridge?

Sergeant Basilone: No, we were right in the jungle.

Captain Martin: Right down in the jungle. Tell me about this using your pistol while you were also operating the machine gun.

Sergeant Basilone: I was lying flat on the deck, firing the machine guns and occasionally, a Jap would rush in from around the side trying to charge us, the fellows would yell, whoever would spot him, and I'd just turn around, grabbed the pistol and fired. I always kept it on the deck right alongside of me.

Captain Martin: When did you have time to load that pistol?

Sergeant Basilone: When I picked up the pistol in the morning, there was one round left.

Lieutenant Porter: Sergeant Basilone, was there any evidence after the battle that the Japs knew where these machine gun nests were?

Sergeant Basilone: Yes, there was. Some of the fellows picked up maps. The Japs had already known where we had been set up—probably had sneaked up on previous days and checked on us.

Captain Martin: From the publicity that's been given this award, I noticed in the press release on it, it said that at one time there was a pile of 38 Japs in front of your machine guns so that you had to change the location of guns. Was that true?

Sergeant Basilone: Yes, that was correct. They were laying all around our guns, we had to change the guns because I had my mounts so low and the Japs being piled there, I had to change my position in order to fire on them.

Lieutenant Porter: Do you mind telling us what happened so that you weren't able to keep the machine gun cooled as it normally would be.

Sergeant Basilone: On, the water being upset and during all that fighting during the night we spilled our water that we had in reserve.

Captain Martin: How long do these guns fire after they are hot? I saw red hot before, were the guns actually red hot?

Sergeant Basilone: Yes, they were, they were really hot because when the bullets were flying out of there, and if it got anywhere near you or touched you, you really were burnt.

Captain Martin: The gun that you carried over from the left flank to the right flank, did it not have water in its jacket?

Sergeant Basilone: It did not have water in its jacket…the one I brought over from the left flank.

Captain Martin: Any idea how many rounds you fired that night?

Sergeant Basilone: No, just a lot of rounds fired, I couldn't tell you approximately how many. The only thing is, there were 126 belts with 250 rounds per belt which is a unit of fire for one machine gun.

Captain Martin: Did you have more than your unit of fire, more ammunition there with you?

Sergeant Basilone: No, we had one unit of fire per gun right at the positions.

Captain Martin: Then, did you actually run out of ammunition?

Sergeant Basilone: We didn't completely run out; we just had about one belt left when we checked on it in the morning.