When it comes to shooting at long ranges—1,000 yds. and beyond—long-action cartridges that hold lots of powder and that propel long, heavy-for-caliber bullets rule the day. Hornady’s .300 PRC fully exploits that concept.

One might think that, at this point in center-fire rifle cartridge development, all of the good ideas have been taken and that there is no room for improvement. Judging by their actions, Hornady’s ballistics engineers disagree with that notion. During the past decade, Hornady has developed and standardized an entire series of cartridges designed specifically for precision use—among the latest is the .300 PRC, which stands for Precision Rifle Cartridge. The .300 PRC was designed from the ground up to engage targets at extreme distances by accurately launching long, heavy bullets with high ballistic coefficients.

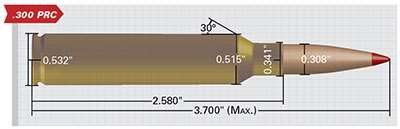

The .30-cal. magnum category is one of the most crowded spots in the rifle cartridge world, with no fewer than nine factory chamberings today. That said, the shooting world didn’t know that it needed another 6.5 mm cartridge when Hornady introduced the 6.5 mm Creedmoor in 2007, but that cartridge has quickly become one of the most popular choices for competition, hunting and general target use. Hornady then adapted the successful design elements of the Creedmoor to a larger cartridge capable of additional power and range. In many respects, the .300 PRC is a scaled-up version of Hornady’s 6.5 mm PRC. To get there, Hornady necked-down its beltless .375 Ruger to .308", gave it a 30-degree shoulder, and kept the case’s body taper to a minimum. Overall length is 3.7", so a magnum-length magazine is a must.

But, again, why? There are plenty of .300 magnums available, but none of them are perfect. Hornady examined the shortcomings of each and addressed them in its new design. The .300 Win. Mag. has been the most popular .30-cal. magnum since the 1960s, but, like most cartridges of its era, it has some significant shortcomings. For starters, the cartridge headspaces off the belt which, as Hornady ballistician Jayden Quinlan explains, is a bit like trying to hold a pencil straight by gripping the eraser. In a shoulder-headspacing cartridge there are two points of contact fore and aft, and it is far more likely that a bullet will be aligned with the chamber as it begins its path. “The belt does nothing for you in the accuracy department,” Quinlan said. “It’s either neutral or it hurts you.” Sure, a belted magnum can be accurate, but it is starting out at a natural disadvantage. And, yes, handloaders can easily set up their dies to headspace the .300 Win. Mag. off the shoulder, but factory ammunition so loaded would not be to spec. The idea of the .300 PRC was to achieve all of the benefits of handloading in a factory cartridge.

The next design element that sets the PRC apart is the cartridge’s throat diameter and geometry. One of the most critical factors in accuracy and bullet stability is whether the projectile is traveling straight when it enters the bore and engraves on the rifling. Most cartridges, the .300 Win. Mag. included, have throats sufficiently large to allow the bullet to yaw once it exits the case and before it reaches the rifling. One of the factors that made the 6.5 mm Creedmoor successful, and gave it its reputation for excellent accuracy across a broad spectrum of firearms, was the tight throat diameter that keeps bullets on a straight path. The .300 PRC builds upon this same principle. The .300 PRC’s minimum throat spec is 0.3088", meaning that a bullet has only 0.0004" of clearance on each side. For comparison, the throat on the .300 Win. Mag. can measure as large as 0.315" and still be within SAAMI specifications.

The PRC case has minimum body taper in order to maximize propellant capacity along its length. Its capacity is purposely designed to be compatible with specific powders and bullets appropriate for long-range use. Bullets on the heavier end of the spectrum, those that are particularly useful at extended distances, have to be seated deep inside the case in cartridges such as the .300 Win. Mag., which eats up critical powder capacity. Both the chamber throat and the cartridge case of the .300 PRC can accommodate long, heavy bullets such as the new 250-gr. A-Tip without compromising velocity. It is worth noting that this bullet has a G1 ballistic coefficient of 0.878, almost double that of 190-gr. match bullets commonly used in the .300 Win. Mag. Extra powder space in a cartridge case isn’t a good thing, either, since it can lead to what’s called “positional sensitivity,” which can cause velocity spreads and is exacerbated by temperature extremes. The .300 PRC is designed for a full powder charge to sit just at or below the base of the bullet. “The goal is to get the thing full of powder,” Quinlan told me, “with the bullet of choice using the powder of choice.”

This product was not rushed to the market to meet a fad. Hornady had been using the .300 PRC in its own testing facilities for eight to nine years before it was put through the SAAMI standardization process and offered commercially in 2018. When Hornady released the .300 PRC, rifle makers were quick to respond, and numerous models were chambered for the cartridge within months. Two early examples were the Ruger Precision Rifle and the Barrett MRAD (Multi-Role Adaptive Design). I obtained samples of each in order to put the cartridge thoroughly through its paces.

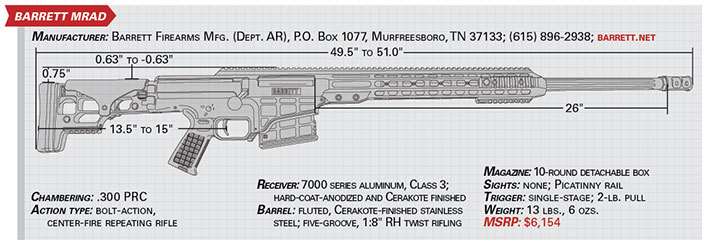

The MRAD is a three-lug bolt-action repeater fed by a 10-round detachable box magazine. The entire rifle is built around a rigid aluminum chassis that serves as both the stock and receiver. Barrels are secured in place by a pair of Torx screws and can be readily exchanged without specialized equipment or training. The stock is fully adjustable to fit individual shooters and optics, and it folds onto the right side of the receiver to make the rifle more compact for transport. The MRAD is available in seven different chamberings ranging from 6.5 mm Creedmoor to .338 Lapua Mag. My test sample was chambered in .300 PRC.

In March 2019, americanrifleman.org reported the adoption of the MRAD by the United States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) as the new Advanced Sniper Rifle. One of the requirements for the platform was the ability for the end user to be able to change barrels and chambering, something that the MRAD was specifically designed by Barrett to do. The USSOCOM contract calls for barrels in 7.62x51 mm NATO, .300 Norma Magnum and .338 Norma Magnum, though at least one military unit has adopted the rifle in .300 PRC.

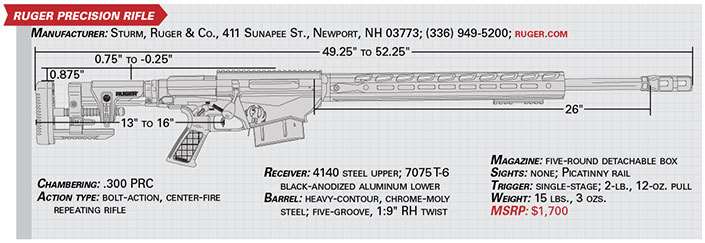

In early 2019, Ruger announced that the .300 PRC would be available in the popular Ruger Precision Rifle (RPR). The RPR shares many features with the Barrett, including a side-folding adjustable stock, a three-lug bolt, and a detachable box magazine. Ruger’s RPRs have quickly built a reputation as being extremely accurate, affordable rifles, and this example was no exception.

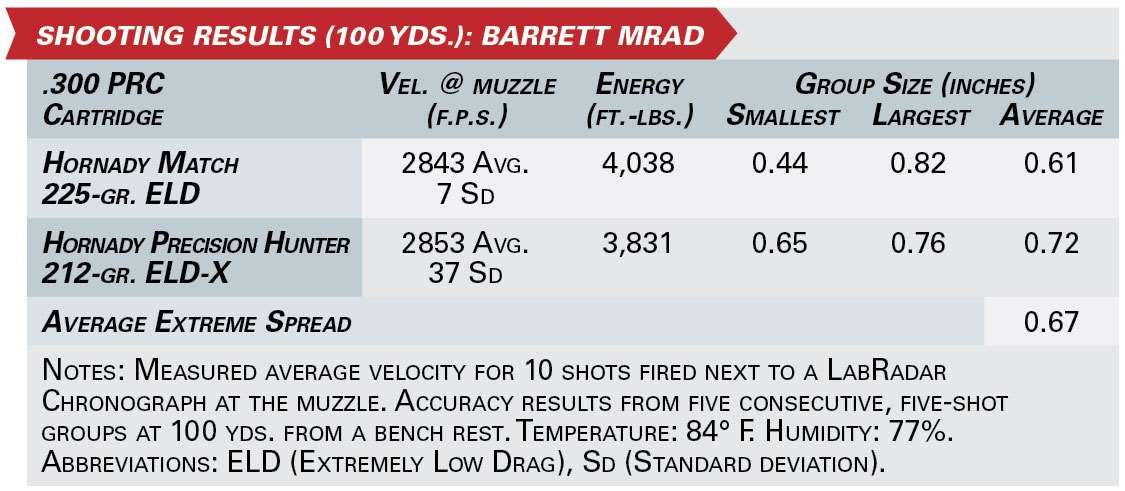

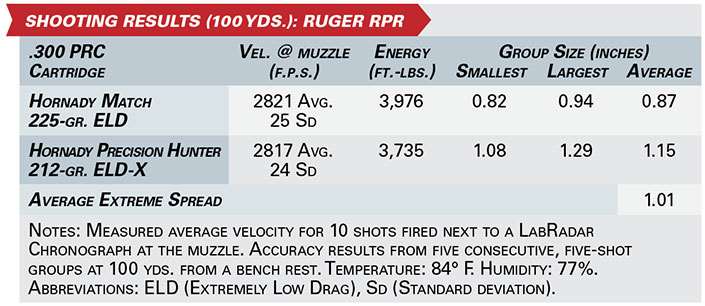

I fired both rifles using both the Hornady 225-gr. ELD Match and 212-gr. ELD-X Precision Hunter ammunition, and mounted Leupold Mark 5HD scopes on each—a 5-25X 56 mm model on the Ruger and a 7-35X 56 mm model on the Barrett—before recording both accuracy and velocity figures. Firing rifles and cartridges designed for long-range precision at 100 yds. alone wouldn’t be much of a test, though, and these rifles begged to make hits at distance. My personal range only allows for shots out to 400 yds., so I had to make other arrangements. Barbour Creek Shooting Academy (barbourcreek.com), located outside of Eufaula, Ala., is a first-class long-range training facility with elevated, climate-controlled shooting positions and steel targets out to 1,000 yds. After testing these rifles extensively in the August heat and humidity of South Alabama, shooting inside an air-conditioned room was almost too good to be true.

With Barbour Creek’s owner, Mark Simpson, on the spotting scope, we confirmed my 300-yd. zero with both rifles before moving to more distant targets. I’d input both the cartridge and environmental data into the Applied Ballistics ABMobile app on my iPhone so I had detailed bullet drop, spin drift and wind data out to 1,000 yds. at my fingertips. Barbour Creek’s target array is a series of 12" plates at 100-yd. increments, each with a 2.5" orange dot as an aiming point. I started with the MRAD and began shooting, adjusting parallax and dialing for elevation at each target in succession. My personal preference for this type of shooting is to dial for elevation and use the reticle to hold for wind, which is exactly what I did. Winds were light and varied from 3 to 5 m.p.h., which is still enough to cause more than a foot of horizontal drift at these distances.

The rifle, cartridge, ballistic data and scope adjustments all held true to the 900-yd. line, with zero misses along the way. At 1,000 yds., I made a 5.9-mil elevation adjustment and held dead-on since the spin drift created by the barrel’s right-hand rifling twist would virtually cancel out the right-to-left wind. I thanked my friend Chris Barrett for this rifle’s excellent trigger as I tried to minimize the effect of my heartbeat through the scope’s 35X magnification. As the first shot broke, I lost the target in recoil. “Hit,” Mark reported. I made the same hold and sent another round, “Hit, good shot.” I sent the third round. “Just left, wind picked up a bit.” When we examined the group, the horizontal spread between two of the hits was just larger than the 2.5" dot and the deviation in elevation was even tighter. Had the wind not pushed the third shot a few inches to the left, the group would have measured 0.3 minute of angle (m.o.a.); not bad for a factory rifle using production ammunition at 10 football fields.

We repeated the process with the Ruger Precision Rifle, starting once again at 300 yds. and working our way downrange. Just as we experienced with the MRAD, our hits were consistent with the ABMobile data all the way out. We had a nice triangle-shaped three-shot group at 1,000 yds. that measured an honest 5". Overall, I was impressed by the consistency of the ammunition, the accuracy of both rifles and the precise adjustments of both Mark 5HD scopes.

Finally, it was my turn on the spotting scope as Simpson took aim with one of his own company’s custom rifles chambered in .300 PRC. His rifle was more traditional in design than the two test rifles and, at roughly 9 lbs., was more appropriate for most hunting scenarios. This rifle didn’t suffer in the accuracy department, either, and Simpson dialed straight for the 1,000-yd. target and shot a three-shot group that most rifles would love to shoot at half that distance.

The past decade of cartridge development, combined with the shooting community’s focus on long-range accuracy, has led us to places we could not have imagined even as late as the 1990s. Hornady’s scientific approach to cartridge and bullet design is leading much of the change that we have seen, and the results are extremely impressive. The .300 PRC isn’t the end of the road, either, as I suspect we will see further innovation in the years ahead.

It’s an exciting time to be a rifleman.

Leupold’s Mark 5HD

An accurate rifle shooting the greatest of ammunition is worthless at long range without an equally functional riflescope. Optics that won’t hold zero and adjustments that don’t track consistently are a no-go when the ranges get long. Leupold’s newest long-range optic is the Mark 5HD, a series of scopes designed with extreme ranges and conditions in mind. I tested two examples, the 5-25X 56 mm and the brand-new 7-35X 56 mm. Both scopes use 35 mm tubes, which give them plenty of room to make the necessary windage and elevation adjustments required for this type of shooting. Mark 5HD scopes are available in either mils or m.o.a. adjustments, and I chose the former for both optics.

Users can choose from three first-focal-plane (FFP) reticles so that elevation and windage holds can be made using the reticle at any magnification setting. I found the reticles to be both useful and intuitive, and there was no need to consult the manual in order to figure out the correct wind holds.

Mark 5HD scopes are the lightest in their class yet, according to my experience, give up nothing in terms of performance. Our 7-35X 56 mm was secured to the MRAD using the excellent Spuhr Ideal Scope Mounting System, a product that not only secures the optic well, but ensures that elevation adjustments take place on a perfect vertical plane thanks to its integral leveling system. I fired hundreds of rounds of .300 PRC and 6 mm Creedmoor to test these two optics, and both showed extremely impressive results.

—Keith Wood