The involvement of the United States in World War I resulted in many interesting stories of the production of small arms to equip the rapidly expanded military that was required for the conflict. There is one story, though, which has gone largely unnoticed by the modern collecting community. Through our efforts, we seek to correct this and bring to light an interesting and often misidentified variant of the M1911 pistol, which has what we believe is a Springfield Armory-produced and -marked slide and a Colt frame, assembled by Colt as factory pistols.

Before getting into details, it's worth exploring why Colt ended up in the position of needing help in completing guns. The implied promise that followed the Wilson campaign slogan "He kept us out of the war," is one of U.S. history's most famous broken presidential campaign promises. While Woodrow Wilson narrowly won reelection in 1916 against Republican candidate and Supreme Court Justice Robert Evans Hughes, as a series of international crises unfolded, the United States found it impossible to stay out of the European conflict. On April 6, 1917, Congress formally declared war on Germany and its allies. But there was a significant problem: the official stance of neutrality by the U.S. government had prevented the funding and procurement necessary for entering the conflict which currently raged on an unheard-of scale, and the United States was suddenly faced with the prospect of having to raise a one-million-man army.

This raised the question: how would they arm this million-man force? The United States had thus found itself amidst a dire shortage of military firearms and equipment of all kinds, though most pressing was the need for rifles and pistols. To address this, Brig. Gen. William Crozier, chief of U.S. Army ordnance, authorized the adoption of substitute standard weapons to serve alongside the standard Springfield Model of 1903 rifle and Colt M1911 pistol for the war in Europe. The 30-cal. U.S. Model of 1917 rifle, and .45-cal. U.S. Model of 1917 revolvers made by Colt and Smith & Wesson provided sterling service in that capacity until production of the standard firearms could be ramped up.

To further complicate matters, the Commanding Officer of Springfield Armory, Col. William Pierce, notified Brig. Gen. Crozier that pistol production was not separate from rifle production. Pierce informed him that this created a choke-point for rifle production, because pistol production utilized some of the machinery necessary to produce rifles. He requested that pistol production be ceased at the armory to maximize rifle production. It was also recommended that pistol production be sourced elsewhere. Crozier approved this recommendation on April 13, 1917.

A natural choice to help increase production of the standard sidearm, the Model of 1911 semi-automatic pistol, was of course Colt. Since the 1830s, Colt had enjoyed a relationship with the U.S. military, and had initially been the sole supplier of the M1911. Government contracts in large numbers were not a foreign concept to Colt, as they had, prior to the adoption of a semi-automatic pistol, produced a wide range of U.S. martial revolvers including the Model 1860 Army, the Model 1873 Single Action Army, along with a line of double-action, .38-cal. revolvers, the Model 1902 and the Model 1909.

In a War Department memo dated Feb. 5, 1917, nearly two months before the US entered the war, Colt forecast the following delivery schedules for pistols and revolvers.

|

Number |

Month |

Number |

Month |

|

500 |

February |

5,000 |

August |

|

2,000 |

March |

5,000 |

September |

|

2,500 |

April |

5,000 |

October |

|

3,000 |

May |

6,000 |

November |

|

4,000 |

June |

6,000 |

December |

|

4,000 |

July |

|

|

To help further alleviate the shortage of sidearms, Colt further promised to furnish the new service revolvers, .45-cal. (Model of 1917 revolvers) at a rate of 450 per week during the month of March, and from April 1 thereafter, at a rate of 600 per week.

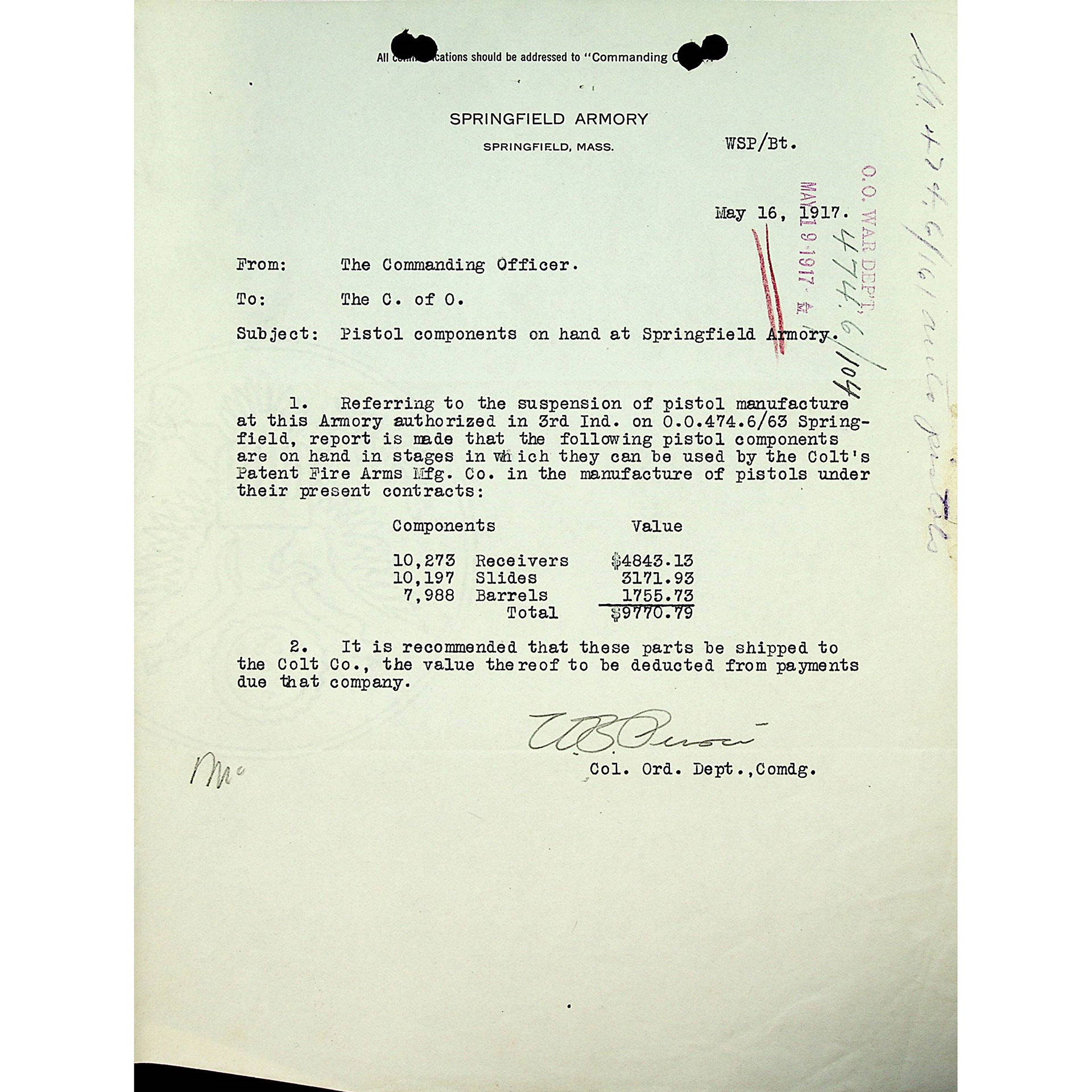

There was little patience for delays and shortages, however, as the War Department was already behind in properly sourcing the equipment needed to fight a war that had engulfed most of the globe. On May 16, 1917, Col. Pierce at Springfield Armory sent the following recommendation to the Chief of Ordnance:

Referring to the suspension of pistol manufacture at this Armory authorized in 3rd Ind. On O.O.474.6/63 Springfield, the report is made that the following pistol components are on hand in stages that can be used by the Colt's Patent Fire Arms Mfg. Co. in the manufacture of pistols under their present contracts:

|

Number |

Components |

Value |

|

10,273 |

Receivers |

$4,843.13 |

|

10,197 |

Slides |

$3,171.93 |

|

7,988 |

Barrels |

$1,755.73 |

|

|

Total |

$9,770.79 |

In May, Gen. Crozier expressed his disappointment when he was notified by a telegram from Springfield Armory that Colt was delivering principal parts daily but not complete pistols, despite the desperate need for them. He asked Col. Skinner, an ordnance officer assigned to Colt, if he could rectify the situation. Also in May, the War Department created a verbal inquiry as to what Colt would charge for a contract on 500,000 semi-automatic pistols.

Colt notified the War Department and General Munitions Board that its pre-war pricing of $14.50 per pistol (with one magazine) and $0.50 for each additional magazine would not be possible. They further stipulate that the company's overhead costs were up dramatically across the board. It stated that labor costs were up 50 percent, materials were up 100 to 300 percent and there was an excess profits tax of 8 percent, with a threat of more. The company further detailed that profits the previous year were derived almost entirely from commercial pistol sales. They further state that they have taken staffing and machinery away from commercial production and put them to work in government production.

To alleviate these changes, Colt anticipated needing a larger capacity to meet the government requirements. However, due to the costs associated with building, heating, lighting, machinery, tools, fixture, etc., the labor and material price would cost approximately $4.25 per square foot compared to the costs of $1.50 per square foot before the war. To be more concise, Colt saw an increase in all expenses, which would have to be reflected on contracts moving forward, especially during wartime production. Complications associated with wartime production were about to go from bad to worse, however, there was a silver lining. The chairman of the General Munitions Board advised Gen. Crozier that the increased pricing is "fair and just." Colt accepted the order for a contract on 500,000 semi-automatic pistols and 100,000 revolvers on June 4, 1917.

On Dec. 10, 1917, the Chief of Ordnance advised the Adjutant General of the Army that, based on the recently approved tables for an army of 1,612,000 men, it would be necessary to provide (before Jan. 1, 1919) a total between 1,300,000 and 2,000,000 pistols/revolvers based on the assumptions made as to reserve and wastage. It should be noted that the Chief of Ordnance only had 55,553 M1911 pistols on-hand at the beginning of the war in 1917. Crozier further advises that current output cannot be expanded much beyond 75,000 pistols/revolvers per month without developing new sources of supply. The U.S. Army wanted to fight but faced an unexpected enemy: supply issues.

By January 1918, patience was running razor-thin. On the 28th of that month, Colonel Dickson wrote a strongly worded memorandum to Col. Tripp of the Production Division:

"Colonel Thompson, Ordnance Department, informs me that the progress made by the Colt Patent Fire Arms Company of Hartford, Conn. in the production of Colt pistols, U.S. service type, has not been satisfactory. The lack of 45-cal. pistol production is causing the Acting Chief of Ordnance serious apprehension and embarrassment. He instructs me to request that you have a very diplomatic but thorough investigation of the situation, including lack of thoroughly competent supervisory assistance to the Works Manager."

In April, the Ordnance Department also noted that the Army was behind 1,000,000 pistols, and Colt, Winchester and Remington would not be ready to produce 3,000 per day until February 1919.

Colt was not passive in finding solutions to its production setbacks. In early 1918, the company began petitioning permission to build a larger facility specifically for pistol production. The Chief of Ordnance sent an inquiry to the War Industries Board for approval. The board responded the following May:

"Attention is invited to the enclosed memorandum relative to increasing the capacity to manufacture Colt Automatic Pistols. It has been reported to the War Industries Board that consideration is being given to an increase in present plant facilities within the congested New England area. However, the fuel and transportation shortage is so great within this region that the President has directed that no new plants or additional facilities to old ones be placed there except upon the approval of the War Industries Board. Therefore, it is inadvisable to do anything requiring an additional amount of coal in this area."

Colt, however, was able to put a second shift for increasing output. Putting together two shifts of 10 hours each, they were looking to have an entire second shift operational as quickly as possible. Unfortunately, still, it was not fast enough to meet the demands of the War Department, which soon started imposing financial penalties on Colt for its failure to produce the required number of guns.

In May 1918, the vice president of Colt, S.M. Stone, wrote to the chief of ordnance requesting a formal investigation, stating that the penalties imposed by the government on Colt due to lagging pistol production were severe and pleading for relief from them. He noted that the situation resulted in a reduction in Colt's production capacity. As part of his explanation, Stone highlighted the fact that, for other manufacturers to deliver their pistols as soon as possible, Colt was expected to give them every assistance. This included providing detailed descriptive drawings, master drawings, gauges, educational instruction and sending representatives to several factories. He further stated that Colt had not held any information back or any possible assistance.

Still, the performance of the duties and conditions imposed by the government had been at the expense of Colt's production of both machine guns and semi-automatic pistols, although he stipulated that it's more particularly in the latter's case. Such was the situation when Stone invited an investigation and requested relief from the penalties. On May 27, 1918, Lt. Col. Earl McFarland (who would later serve as superintendent of Springfield Armory on two separate occasions) submitted his report on that investigation. Several of the points made are as follows:

- The contract for semi-automatic pistols was made on Sept. 28, 1917. It covered a total of 500,000 (a very considerable number), extending over a long period of time with promised deliveries announced at approximately that time and long before accurate manufacturing data was available.

- The data estimated or promised deliveries given by Colt appears to be have been a little more than a guess, and it would have been awarded the contracts irrespective of whether this guess had been made short or over.

- Companies subsequently accepting orders for semi-automatic pistols did so with much more knowledge of manufacturing conditions than did Colt. They made their estimates more liberal to themselves and some cases, were permitted to have a penalty clause left out of their contracts.

- The United States government, before the extensive expansion at the Colt plant, found it desirable that Winchester, Remington, New England Westinghouse and Marlin-Rockwell Corporation take on the number of Browning machine guns and automatic rifles, and in addition, found it desirable to have Winchester and Remington take on the manufacture of the Colt semi-automatic pistol.

- The government requested Colt to give these manufacturers every assistance by way of providing detailed descriptive drawings, manufacturing drawings of various kinds, offering samples of arms, taking representatives of these companies through the different parts of their plant to illustrate their methods of manufacture, explaining difficulties encountered and outlining the methods of correcting such difficulties.

- It is believed that Colt withheld no information that it was possible for them to extend and that the company was most liberal and broad-minded in its attitude toward the government and toward assisting the production of the firearms with which it was familiar.

- In view of the above, the office was inclined to be favorably disposed toward a liberal policy in reference to the assessment of liquidated damages from Colt on account of the pistol and Browning machine gun and automatic rifle contracts, and while it would be difficult to calculate the exact amount of the time lost by Colt on account of the circumstances enumerated above, it was felt that in justice to the general attitude of the company, at least a portion of the liquidated damages should be waived if the legal aspect of the situation would permit such a procedure.

Based on this report, the Chief of Ordnance recommended that 75 percent of the liquidated damages on the pistol contracts be waived. Colt would finally get some good news in this favorable report that they were held back by the government in their ability to deliver on their contracts. This appeared to be the last of Colt's hassles from the chief of ordnance or the War Department. All contracts were canceled in December of that year because the Armistice, and the Great War was finally ended.

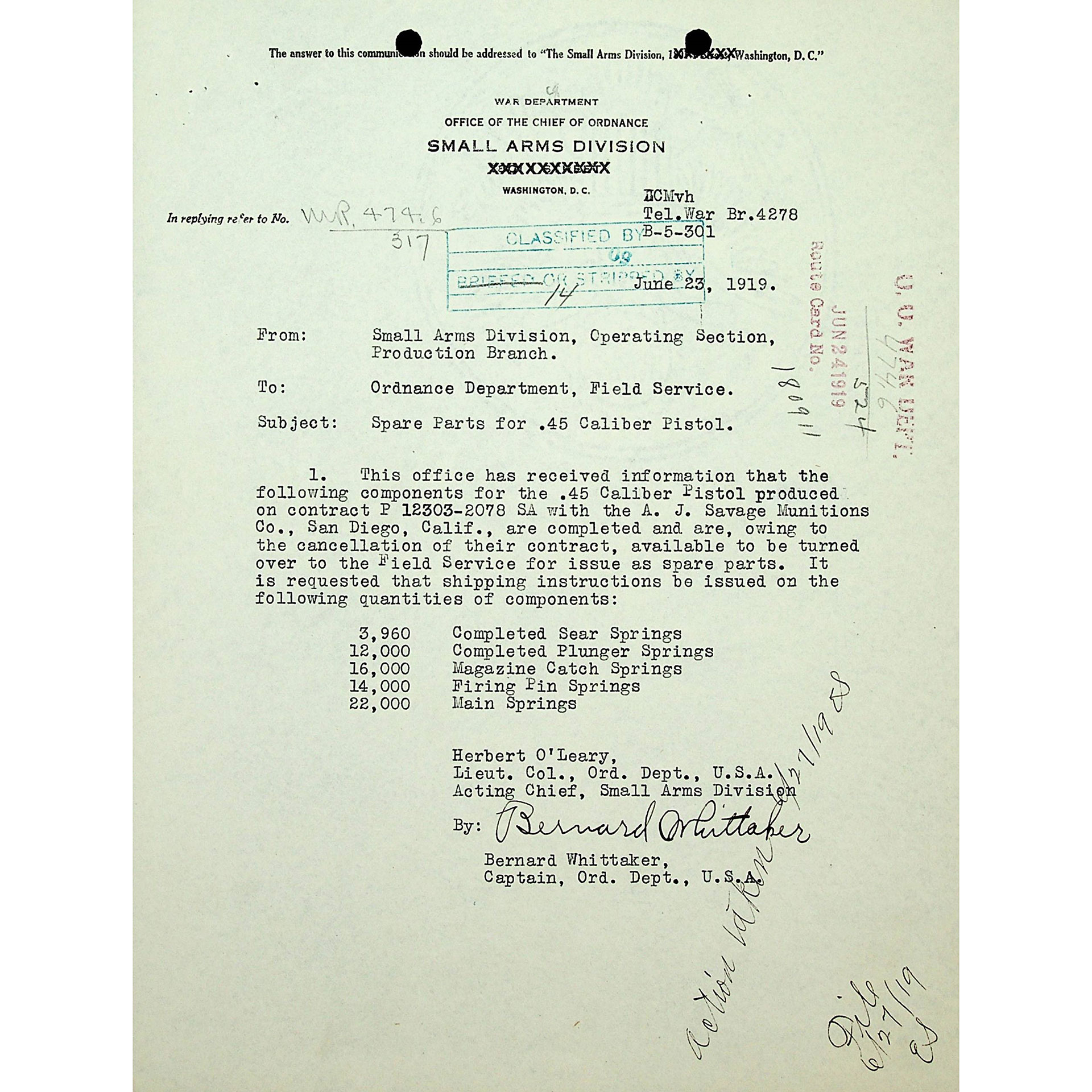

Wartime production problems, the national crisis and the under-equipped army created a perfect storm for manufacturers in the United States. The documentation of Colt's production issues compared against those outlining the history behind an elusive M1911 slide likely produced by Springfield Armory has made for quite an exciting story. Prior to this discovery, it was a commonly held belief in the collecting community that these slides were produced by a small contractor for M1911 parts at the time: A.J. Savage Munitions Company.

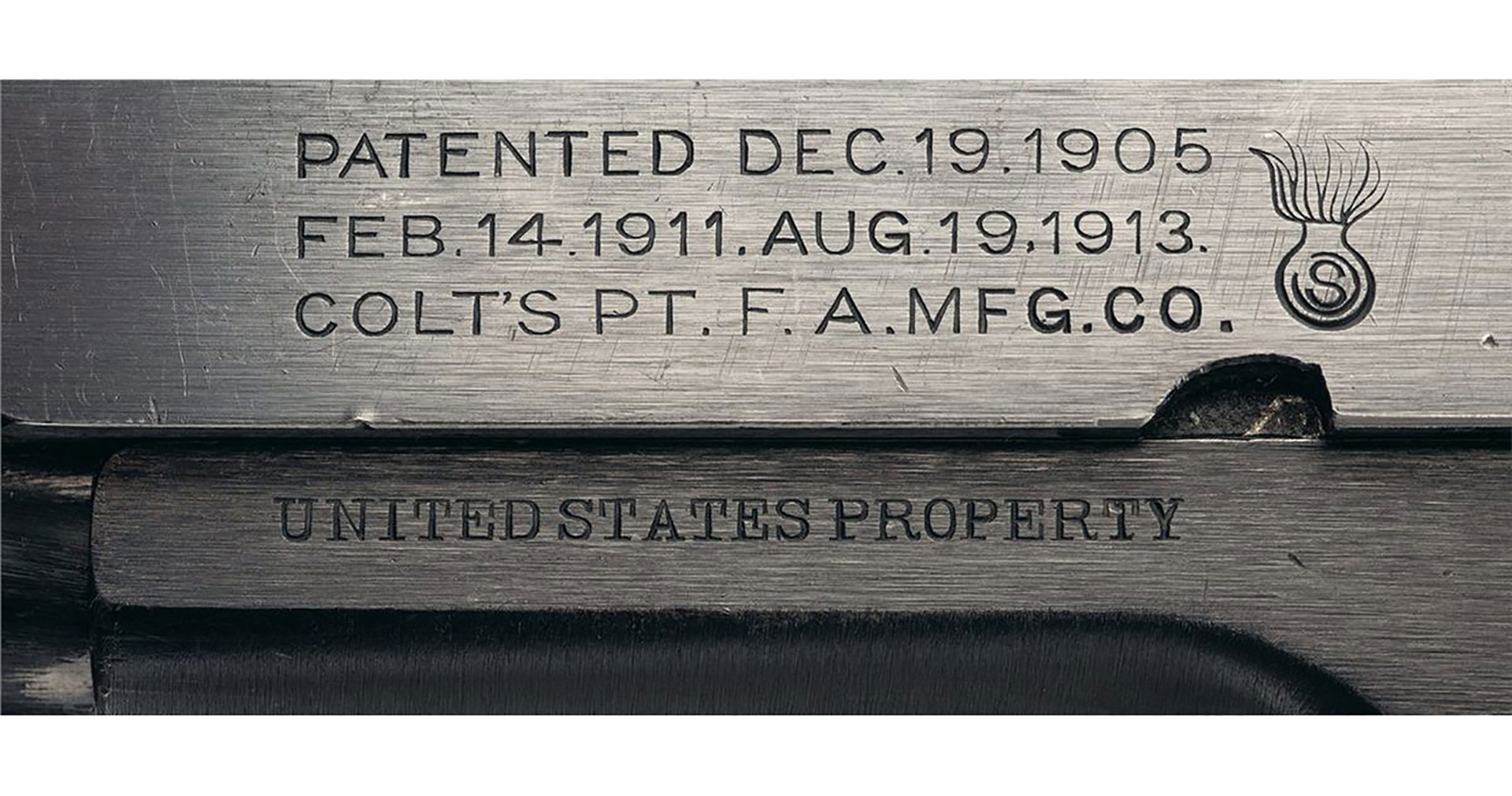

The A.J. Savage Munitions Company was founded by Andrew Savage. He left the Savage Arms company due to family complications, moved to California and started the A.J. Savage Munitions Company. In July 1918, the A.J. Savage Munitions Company was awarded a contract for 100,000 pistols. They were expecting to begin manufacturing and delivering M1911 pistols by 1919. It's been long theorized that, although he completed no pistols, he was able to manufacture some pistol components in late 1918 before his contract was canceled. One part that was believed to be of A.J. Savage manufacture were slides that were marked with the symbol of an "S" within the ordnance escutcheon (sometimes referred to as "flaming bomb" by collectors).

Such theories were that these were Savage slides that were sold surplus to the commercial market after the war. This is unlikely for two primary reasons:

- Several examples can be found with a matching Parkerized finish, suggesting a legitimate arsenal overhaul.

- Any products produced under the auspices of a military contract would become the property of the U.S. government and would be turned over to the Army at any stage of the manufacturing process.

The other theory is that these slides were sent to Springfield Armory after the war and used as replacement slides during the overhaul, as there would be a significant need for spare parts to rebuild and repair pistols used in combat. Ohio-based collector and researcher Steven Norton was the first to notice that this symbol was not exclusive to M1911 slides but was found on pre-World War I Springfield Armory M1903 barrels. It warranted further investigation. Another collector in California, Steve Poplar, brought it to the authors' attention that several M1911s bearing this slide in a brush-blued finish had the following characteristics.

- Matching brush-blued finish.

- 1918 Colt frame.

- SP (Springfield) marked barrel.

The high frequency of these traits could not be overlooked. Historian Alex Antonopoulos, based in Boston, pointed out that it is doubtful the U.S. government would authorize a symbol that so closely resembles a current in-use government symbol. The authors contacted the Patent and Trademark Office, and it found no trademarks filed by either A.J. Savage Munitions Company or Andrew Savage. Furthermore, it stated that the previous comment concerning the unlikely scenario of that symbol being authorized was correct. The trademark office said that its longtime practices are that the symbol would have to be significantly changed from a government-used mark.

It should also be noted that Remington UMC was ordered to send two semi-automatic pistols to A.J. Savage in late-September 1918, presumably to help them know what the finished product should look like. Its contract would be canceled not even three months later. It's unlikely they were in a manufacturing stage to be able to produce significant pistol components. In June 1919, the Ordnance Department was made aware that A.J. Savage Munitions Company would be shipping more than 67,000 springs to repair pistols during overhaul. No mention of slides was made. It was apparent that A.J. Savage only produced springs, and the company was in the very early stages of manufacturing pistols for the Army.

Alex Antonopolus also pointed out another fascinating point concerning the nose of the slides. The milling in the area of the slide nose, immediately above the recoil spring housing, on the replacement slides is not consistent with that seen on slides manufactured by the Springfield Armory. On slides made by Springfield, the profile of the cut at the end of the run is a very abrupt downturn, terminating approximately 3/16" from the nose of the frame, whereas on Colt-made slides of the same era, the end of the cut is a gradual, or "feathered," curve, coming to within approximately 1/8" of the nose of the frame. This sort of milling is seen on the replacement slides and suggests that the slides sent to Colt by Springfield were in a state of incomplete machining or not even machined at all.

What was the purpose of these slides? If not manufactured by Savage, then by whom? To answer this, the authors had to look at all the documentation that crossed the chief of ordnance's desk concerning this issue. The transfer of receivers, slides and barrels from Springfield Armory to Colt in January 1918 is the biggest clue. Springfield Armory needed pistols to send to the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), and Colt needed to produce pistols as fast as possible to deliver on that contract. The deduction of the values from the arrangement of these components is very significant. Springfield Armory needed pistols but did not want to repurchase them when they supplied the parts.

Furthermore, if there were an issue, such as a manufacturing flaw in these components, Colt would not want to take responsibility for something that was not exclusively a product of its labor. The solution would be to mark the pistols to distinguish them from regular Colt production so that Springfield would not be buying back its property. It would also offer some protection for Colt, should an issue arise from these pistols in the early manufacturing processes. It is the belief of the authors, after considering all the suggestions and input from the collecting community as well as the primary source documentation obtained at the National Archives, that these pistols, if found with a brushed blued finish, with 1918 Colt frames, SP-marked barrels and these slides, may be factory-original examples from Colt.

It is the belief of the authors that Springfield stamped slides that it produced with the "S" within the ordnance escutcheon to mark them as produced (and paid for) by Springfield Armory. They were in various states of finishing. When they were sent to Colt, the manufacturing steps were finished helping Colt increase its production. It is also the belief of the authors that slides with "S" within the ordnance escutcheon are not produced by A.J. Savage and instead by Springfield Armory for the reasons mentioned above.

Given the urgent need for pistols, Colt's unwavering flexibility, and Springfield Armory wanting Colt to produce pistols as fast as possible, these pistols offer an example of a short-lived, sub-variant of the M1911 that was born out of wartime necessity. There is no evidence that A.J. Savage produced anything other than springs. The U.S. government would have never authorized the use of the minimally modified ordnance echelon as a trademark for Savage. The only transfer of parts between Springfield Armory and other manufacturers that were notable was between Springfield Armory and Colt in January 1918. At the present time, all evidence, in terms of primary sources and physical examples, all point to the fact that these guns were developed as a wartime-expedient and a hybrid between the two entities (Colt and Springfield Armory).

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the following individuals for their contributions to this article: Alex Antonopolus, Joe Holden, Lars Gill, Steve Norton and Steve Poplar. The collaboration, sharing of ideas and weighing of all the evidence helped make this piece possible. It's a testament to how, more than 100 years later, discoveries regarding the M1911 story can still be made, and another chapter has been added to its fascinating story. For more information, visit archivalresearchgroup.com.